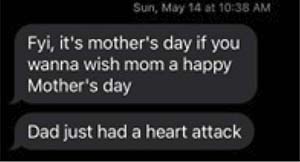

On a beautiful summer day in Buffalo, NY I found myself a few hours into the morning shift at the small stand-alone emergency department we rotate through as first-year residents. It was Mother’s Day and I had made sure to send a morning text to my Mom wishing her a great day. As an intern, I was enjoying the experience of working in a different environment and I was beginning to get a feel for the differences in workflow not being at one of our program’s larger academic hospitals. I was excited because later in the week I was going to a big national conference in Austin where I had some friends living and was going to cheer on our Sonogames team. Suddenly, a young girl was brought in by her mother with an object surrounding her hand… what is that? I immediately stopped dictating a note and evaluated the patient, seeing an entire blender around her hand with the blade secured into one of her little fingers. I initiated the appropriate treatment and work-up (including a more appropriate than usual tetanus shot) and quickly facilitated transfer to our children’s hospital. After some shared collegiality with one of our pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) attendings, I hung up the phone to see my cell phone light up with a text message from my brother.

New York American College of Emergency Physicians

Grief Burdened by Knowledge Finding motivation through loss during residency

A great older brother ensuring I reached out to our Mom nonetheless.

“Dad just had a heart attack.” What? Out of immediate confusion, I called my brother for clarification – my family isn’t in healthcare and maybe there was some misunderstanding. How would he know he had a heart attack? He told me that our Mom just called him to let him know and he wasn’t sure what was happening because she was hysterical. I quickly hung up. Why would they contact my brother and not me if this is serious? I called my Mom and there was no response. I called my sister who was living with my parents in Virginia at the time and she told me the EMS crew is doing CPR. CPR? What the hell do you mean CPR?I asked her “Who is in the room? How many people? Is a paramedic there? Is he hooked up to a monitor?” Overwhelmed she says “I’m not sure, I don’t see a monitor?” I asked her to give the phone to one of the EMS providers.

A gentleman said “Hello” and I calmly said, “Hi this is the son of the patient, I am an ER physician, what is going on?” He let me know that my dad is receiving compressions from a LUCAS device. They could not get IV access and needed to get IO access. They had been running the code for approximately 12 minutes and my sister had done CPR for 6 minutes or so before they arrived. I asked what my Dad’s rhythm was during pulse checks… There was silence. Why is there silence? Are you checking for a shockable rhythm?? After some pause he says asystole. I asked what the initial rhythm was, he said asystole. My eyes well up as I pace in the back hall of the standalone emergency department, ancillary staff starting to become aware something must be happening. I think to myself “Wait, is my Dad actually not going to make it?” I am still on the phone and the advanced EMT tells me there are two paramedics on the scene. I asked if they intubated and he said they attempted and couldn’t on one attempt – only a supraglottic device could be placed. I shake my head as my adrenaline continues to surge, this is over.

The EMT starts telling me his son is also an ER doctor, I share a few kind words clearly confused about how this is a point of conversation and then ask to speak with the paramedic on scene. I asked what hospital in Virginia is providing medical direction and where they are in regard to terminating the code. A few minutes go by and he lets me know my Dad has unfortunately died.

I let the attending I was working with know what had happened, holding back tears. He immediately told me to leave and to not worry about anything else but being with my family. He offered to buy me a flight home if I needed it and shared his number stating he’ll let the chiefs and appropriate faculty know. I gathered my belongings and walked out to my car in a complete daze. I had managed to hold it together until I closed my driver’s seat door and then my emotions flooded out. How is this possible? My parents had just visited me in Buffalo for the first time since residency began two weeks prior and I gave them a tour of the city, showed them where I work and shared the excitement of my new life with them. My dad had just retired in January, he was supposed to travel the world with my Mom, just how is this possible? After composing myself I drove to my apartment and looked at flights – unfortunately, none were available until late at night. I packed essential belongings in around ten minutes and then hit the road – a ten-hour road trip began.

I learned a lot about myself on that drive. Very early on during my trip, I felt the need to reach out to my program director personally. I let him know what was going on and shared how I was feeling. I found myself going over differential diagnoses as to how this could happen. My Dad had never spent a day in the hospital and I found myself at a loss reflecting on his sudden passing and comparing his fate to that of other chronically ill older patients I have taken care of. I found myself asking for advice about whether to get an autopsy and appropriately, my faculty mentor and program director stated this was a personal and family choice.

I reflected on who my Dad was, having never had surgery and the process of obtaining an autopsy. My Dad wouldn’t have wanted this and nine times out of ten he had an adverse cardiac event. I shared these sentiments with my family and we decided to forego the autopsy. I called my closest friends and shared the news. Disbelief and sadness echoed through each call. I was then alone, driving on the road, playing songs I knew my Dad loved, traveling mile by mile.

I arrived safely at home and I embraced my family. Everyone was still in shock and truly unaware of what he exactly would have wanted as a funeral considering we all believed he had several years still with us. We celebrated the man he was, a lifelong NASA aerospace engineer who had given so much to his family, friends and community. I found myself speaking at his funeral, as the “doctor youngest child”, seen by extended family and friends for the first time in years. As a first-generation immigrant to this country, my Dad loved my public speaking abilities. He would always give me praise whether it was at a casual event, my TEDx talk or thesis defense. I put on one more public speaking performance, just for him.

I returned to residency a few weeks later with a changed perspective. I was starting a month at our children’s hospital and found myself working with the same PEM attending who confirmed the blender blade girl did well. Soon after, I started an EMS/Tox module where I found myself hyperfocused on the pivotal role EMS plays in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Frequently, I was reminded of my Dad considering our critical line of work. I couldn’t help but feel it was unfair I wasn’t allotted the opportunity to use my medical knowledge to help him. From time to time, I will find myself back in those first moments on the phone thinking If only I had been there when he arrested, maybe things could be different. I wish I would have had a video or something to see how it all played out. Was this truly ACS? Was this a PE because he came and visited me? Why was this EMT telling me about his son when my Dad was dying? Stop. Live in the present, embrace the past and allow it to serve you as you move forward. As time goes by, I find myself motivated beyond measure, knowing my Dad now has a front-row seat to the life I create. Part of my motivation likely comes from, to quote some of my Dad’s colleagues, him being a “computational fluid dynamicist of the highest integrity” which is quite a tall order to follow.

I can say with the utmost confidence I would not have been able to rebound in the capacity that I did had it not been for the amazing program support I received. Residency is such a unique process that I feel it’s hard to characterize for someone who has not experienced it. The difference a residency family makes, not only through professional growth but personal growth, is something I feel lucky to be a part of. While my Dad’s death was made more difficult by medical knowledge, the care I provide patients moving forward will only improve as a result of this lived experience I have gone through. Rest in peace, Farhad Ghaffari.