With two hours to go on a busy evening shift, a new patient pops up on the board. The line on the EMR reads 9 mo M. CC: Breathing Problem VS: T 37.9 RR 38 HR 148 SpO2 95%. Everyone else is busy, so you decide to pick up the kiddo.

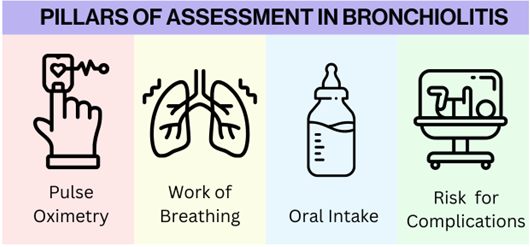

The parents tell you their child was born full term and had no complications at birth; his vaccines are up to date. Parents noticed that two days ago he started with rhinorrhea and nasal congestion and then one day ago began to cough. They feel like his cough has just been worsening and thought he was breathing hard tonight so elected to bring him in. On exam ou find a well-developed baby sitting upright in the parent’s lap. He is interactive and curious. On lung exam you note bilateral wheezing and scattered crackles. As you finish your exam you start to come to a working diagnosis.