Jeffrey S. Rabrich, DO MBA FACEP FAEMS

Senior Vice President

Envision Physician Services

It’s Been a Busy Spring for New York ACEP

We have had a very busy last few months at New York ACEP working on behalf of our members as well as all emergency physicians in New York State. In February, the board of directors approved a brand-new leadership and development fellowship program designed for early career emergency physicians with an interest in pursuing leadership and advocacy opportunities with the organization. The program is one year long and includes attendance and participation with our committees, board meetings, educational programs as well as national ACEP events such as the Leadership and Advocacy Conference (LAC) and the Council. We received interest from several outstanding candidates and after careful review of the applications, we were able to select our first two fellows for the program. The board of directors selected Dr. Samuel Sondheim and Dr. Daniel Novak as our inaugural fellows and we were happy to welcome them at our Advocacy Day in March where they got right to work meeting with Senate and Assembly offices advocating for issues affecting emergency medicine in New York. I would like to thank our Secretary/Treasurer, Dr. Robert Bramante, for helping design the fellowship program and serving as the fellowship director.

Speaking of Advocacy Day, we had many physicians join us in Albany for the day, including residents, to help advocate for issues important to emergency medicine in New York. We had the opportunity to discuss Medicaid rates, excess malpractice insurance coverage, scope of practice issues for physician assistants, violence against healthcare workers, as well as other budget proposals such as moving licensure from the department of education to the department of health. As always there were many proposals that would negatively impact patients as well as the emergency medicine safety net in New York. I am writing this in early May and we still do not have an approved final budget in New York, but your leadership team will be back at it during our leadership lobby day in a couple weeks.

We had another busy week the last week of April as several board members joined other New York ACEP members in Washington, DC for the Leadership and Advocacy Conference which included a chapter leaders session where we were able to exchange ideas with other chapter leaders from around the country and learn what’s working well for other chapters as well as their challenges. There were numerous sessions on effective advocacy as well as sessions with members of congress in the doctors caucus as well as the problem solvers caucus to hear how they are approaching issues is healthcare, most notably the threats to Medicaid funding as well as the Medicare physician fee schedule. During our visits to congressional officers we were able to leverage the finding in the just released RAND report on the challenges facing emergency medicine in the United States and the trends regarding payor behavior over the past several years. If you haven’t had a chance to see the Rand report, you can find it at https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2937-1.html. It’s worth the read which highlights the challenges we are all feeling. After returning from LAC, we turned our attention to our ED Practice Innovations Conference at the New York Academy of Medicine. In addition to hearing about coding and documentation updates, there were several excellent sessions on the use of AI in emergency medicine from the outstanding panel of speakers. The conference was well received by the 100 attendees making this year’s meeting the most well attended since before the pandemic. I would like to thank our practice management committee for putting together a great meeting.

Finally, we are getting ready for our annual Scientific Assembly at the Sagamore Hotel on Lake George July 8-10. Our education committee has put together a fantastic lineup of speakers and registration is open. In addition to the great education and opportunity to catch up and network with colleagues, it’s a great family-friendly venue with lots of activities. I hope to see many of you there and hear your thoughts about how New York ACEP can better serve our membership.

Sound Rounds

Thomas M. Kennedy, MD

Assistant Professor of Pediatrics in Emergency Medicine

Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

Department of Emergency Medicine, Division of Emergency Ultrasound

William Cheng, MD

Pediatric Emergency Ultrasound Fellow

Clinical Instructor of Pediatrics in Emergency Medicine

Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

Department of Emergency Medicine, Division of Emergency Ultrasound

Joni Rabiner, MD

Director, Pediatric Emergency Ultrasound Fellowship

Associate Professor of Pediatrics in Emergency Medicine

Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

Department of Emergency Medicine, Division of Emergency Ultrasound

Scanning Lumps and Bumps: Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Pediatric Head Trauma

Case

A 7-month-old healthy term female presented to the pediatric emergency department for swelling on the left side of her head after a witnessed fall 1 day prior. During a diaper change, she rolled off the bed and fell approximately 2 feet onto the hardwood floor. She cried immediately with no loss of consciousness and no vomiting. She had been acting normally and was observed at home, but on the day of presentation her mother was concerned due to the increased swelling on the left side of her head.

On arrival to the pediatric emergency department, her initial vital signs were: temperature 36.5 °C, heart rate 139 bpm, blood pressure 111/83 mmHg, respiratory rate 38 and oxygen saturation of 97% on room air. On physical examination, she was active and well appearing with a grossly normal neurologic exam. On the left parietal scalp, she had a boggy hematoma approximately 6 cm in diameter. The differential diagnosis for a boggy hematoma after head trauma includes cephalohematoma, skull fracture and underlying intracranial hemorrhage.

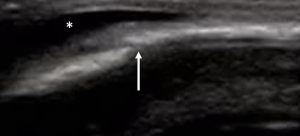

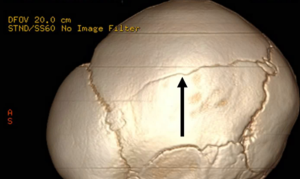

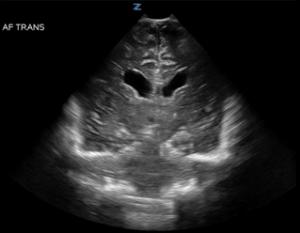

Point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) of the skull was performed in the area of injury and demonstrated a parietal skull fracture with an overlying hematoma (Figure 1). A non-contrast head CT scan was performed which identified a scalp hematoma, a nondisplaced left parietal skull fracture (Figure 2) and an adjacent 3 mm epidural hematoma with no mass effect. She was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit for frequent neurologic monitoring and underwent a non-accidental trauma evaluation.

Discussion

Head trauma is a common cause of presentation to pediatric emergency departments,1 especially in younger children, with symptoms that vary widely based on the severity of injury. The vast majority of children with head injuries have minor head trauma, but it is critically important to identify those with clinically important traumatic brain injury (ci-TBI). Much work has been done to identify characteristics that predict risk for ci-TBI and develop clinical decision rules to risk stratify patients.2 Since the gold standard imaging test for head trauma is a non-contrast head CT scan, clinical decision rules seek to balance the exposure to ionizing radiation against the risk of ci-TBI, such as those that require neurosurgical intervention, intracranial pressure monitoring, intubation, prolonged hospitalization or that cause death.3,4 The Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) algorithm for minor head trauma has been validated for identifying children at low risk of ci-TBI, for whom neuroimaging may be omitted.5

Point-of-care ultrasound for identifying skull fractures is not currently validated for use within any clinical decision rule for evaluating head trauma, but it may offer some diagnostic utility. A meta-analysis showed a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 96% for POCUS identification of skull fractures compared to CT scan,6 as well as feasibility for the emergency department setting.7,8 Hematomas can easily be identified with POCUS as hypoechoic areas above the skull in the area of trauma (Figure 1). It is important to scan the skull under and adjacent to the hematoma, as the fracture may not be directly under the hematoma due to shear forces during the injury.9 Importantly, skull fractures must be differentiated from cranial sutures in young children. Fractures tend to be sharply demarcated and may be displaced while sutures tend to have a more ragged appearance, are not displaced, have contralateral symmetry and consistently trace back to a fontanelle (Figure 3).10

While skull fractures are associated with a fourfold increase in relative risk for intracranial injury,11 it is important to note that skull ultrasound does not evaluate for intracranial injury. POCUS through an open anterior fontanelle may allow for evaluation of central pathologies such as substantial intraparenchymal hemorrhage, mass effect and hydrocephalus, as only the central regions of the brain can reliably be seen, especially as the fontanelle shrinks in size (Figure 4). Enlarged ventricles, midline shift and large fluid collections may be visualized scanning through the anterior fontanelle. Subdural and epidural hematomas may be missed, as the periphery is obscured by bone and the acuity of the angle when scanning through the fontanelle. While ultrasound for skull fracture or cranial ultrasound through the anterior fontanelle does not obviate the need for CT imaging if there is concern for ci-TBI, it may add information of clinical utility at the bedside or be of use in resource-limited settings when CT is not readily available.

Case Conclusion

The patient had no deterioration in neurologic status during admission. There were no additional injuries identified on skeletal survey and a repeat head CT scan demonstrated no progression of the skull fracture or epidural hematoma. She was discharged home on the second day of hospitalization with the plan to follow-up with our Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation service.

Indications

- Blunt head trauma

- Concern for ci-TBI

- Scalp hematoma

Technique

- Place the patient in a position of comfort.

- Apply ultrasound gel, a stand-off pad or a water-filled glove over the areas of interest.

- Use a high frequency linear transducer for evaluation of the skull.

- Use a small footprint transducer, such as the phased array or endocavitary transducer, for evaluation through an open fontanelle.

- Scan the area of interest in two dimensions and trace fractures and sutures to determine if they connect to a fontanelle.

Pitfalls and Limitations

- Skull ultrasound does not permit intracranial evaluation due to the high acoustic impedance of bone.

- The field of view for a fontanelle ultrasound is primarily limited to central regions and misses the periphery.

- Skull fractures are often identified directly underneath areas of scalp swelling but can also be found adjacent to hematomas.

- Skull fractures must be differentiated from cranial sutures. Skull fractures tend to be sharp and linear with varying degrees of depression. Sutures tend to be hypoechoic regions with a beveled or end-to-end appearance that separates bony plates, trace back to open fontanelles and demonstrate contralateral symmetry.

- Neither skull nor fontanelle ultrasound are currently incorporated into risk stratifying algorithms for head injury.

References

- Taylor CA, Bell JM, Breiding MJ, Xu L. Traumatic Brain Injury-Related Emergency Department Visits, Hospitalizations, and Deaths – United States, 2007 and 2013. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2017;66(9):1-16. Published 2017 Mar 17. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss6609a1.

- Lyttle MD, Crowe L, Oakley E, Dunning J, Babl FE. Comparing CATCH, CHALICE and PECARN clinical decision rules for paediatric head injuries. Emerg Med J. 2012;29(10):785-794. doi:10.1136/emermed-2011-200225.

- Lee S, Kim HY, Lee KH, et al. Risk of hematologic malignant neoplasms from head CT radiation in children and adolescents presenting with minor head trauma: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Eur Radiol. 2024;34(9):5934-5943. doi:10.1007/s00330-024-10646-2.

- Kuppermann N, Holmes JF, Dayan PS, et al. Identification of children at very low risk of clinically-important brain injuries after head trauma: a prospective cohort study [published correction appears in Lancet. 2014 Jan 25;383(9914):308]. Lancet. 2009;374(9696):1160-1170. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61558-0.

- Holmes JF, Yen K, Ugalde IT, et al. PECARN prediction rules for CT imaging of children presenting to the emergency department with blunt abdominal or minor head trauma: a multicentre prospective validation study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2024;8(5):339-347. doi:10.1016/S2352-4642(24)00029-4.

- Alexandridis G, Verschuuren EW, Rosendaal AV, Kanhai DA. Evidence base for point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) for diagnosis of skull fractures in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Med J. 2022;39(1):30-36. doi:10.1136/emermed-2020-209887.

- Parri N, Crosby BJ, Glass C, et al. Ability of emergency ultrasonography to detect pediatric skull fractures: a prospective, observational study. J Emerg Med. 2013;44(1):135-141. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2012.02.038.

- Riera A, Chen L. Ultrasound evaluation of skull fractures in children: a feasibility study. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(5):420-425. doi:10.1097/PEC.0b013e318252da3b.

- Rabiner J, Friedman LM, Khine H, Avner JR, Tsung JW. Accuracy of point-of-care ultrasound by pediatric emergency sonologists for the diagnosis of skull fractures. Crit Ultrasound J. 2012;4(Suppl 1):A4. Published 2012 Dec 18. doi:10.1186/2036-7902-4-S1-A4.

- Soboleski D, McCloskey D, Mussari B, Sauerbrei E, Clarke M, Fletcher A. Sonography of normal cranial sutures. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997;168(3):819-821. doi:10.2214/ajr.168.3.9057541.

- Quayle KS, Jaffe DM, Kuppermann N, et al. Diagnostic testing for acute head injury in children: when are head computed tomography and skull radiographs indicated?. Pediatrics. 1997;99(5):E11. doi:10.1542/peds.99.5.e11.

Mark Curato, DO FACEP

Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine

Director, Clerkship in Emergency Medicine

Director Sub-Internship in Emergency Medicine

NewYork-Presbyterian – Weill Cornell Medicine

How to Talk to Your Friends and Colleagues about Our Advocacy Agenda

Each year, a handful of us take a day to travel to Albany to meet with lawmakers to teach them about how various proposed laws would affect the delivery of emergency care in New York. Often, lawmakers’ understanding of the issues is surprisingly incomplete or inaccurate; our efforts can be high-impact.

Everyone has a finite amount of time and energy, so we pass no judgement on our friends and colleagues who are unable to directly participate in our advocacy day. Certainly, though, the issues we’re working on have the potential to affect every one of us, so we should work to incrementally increase the collective awareness however possible.

One strategy for us is to distill the issues down to their very essence, such that they can be described in the briefest of conversations amongst those in Emergency Medicine. Below is a tasting flight of these distillates in the form of conversations which you might adapt and utilize as you see fit.

Colleague: Can I give you sign-out on the guy in bed 4? He’d missed a few days of his Keppra and had a seizure. He was post-ictal at the scene and PD gave him Narcan because there was oxycodone in his medicine cabinet and they weren’t sure if he was an overdose.

You: Did you know there is currently a proposal1 by State Senator Lanza which would require us to research and notify the outside prescriber any time we treat someone for a possible controlled substance related condition?

So, every time an elderly person on trazadone falls and every time EMS administers Narcan to an unconscious person, you’d be legally required to figure out who prescribed the medication and notify them.

Can you imagine the time it would take to do this? For sure it would negatively impact our ability to perform our job and would negatively impact the patients in our care.

Colleague: That’s terrible.

You: Yeah, I know. NYACEP is lobbying hard against it.

RN: Wow. That agitated lady in Bed 3 almost punched me. Thank goodness security was right there.

You: Yeah, whew. But did you know that there is no legal requirement that hospitals provide security guards in the ER? Some hospitals don’t, though we’ve all been affected by verbal and physical violence at work.

A bill2 sponsored by State Assemblyperson Cruz and Senator Sepúlveda would require hospitals to have a workplace violence prevention plan.

It’s not overly prescriptive, but would at least make sure that every ER in New York has a trained security guard.

RN: Will it pass and become law?

You: We hope so, NYACEP is part of a broad coalition lobbying for it!

PGY-1: I was just learning about how little we get reimbursed when we care for patients with Medicaid. It’s a little sus.

You: I know, the Medicaid reimbursement rates in NY are way lower than in neighboring states. And sometimes, they deny payment altogether.

In New York we have an Independent Dispute Resolution Entity (IDRE) which determines whether the fees we charge for our services are reasonable. But there is a proposal3 in the state budget which would eliminate our ability to bring a claim dispute to the IDRE. We’d be forced to accept laughably low Medicaid payments.

PGY-1: That proposal is clearly the work of a Skibidi Ohio Rizz.

You: Huh? Uh, anyway, NYACEP is lobbying against it.

PA: Can we talk about the patient in Bed 7? I have a sense of how I’d like to work her up but I have a couple questions.

You: Of course. But be aware, there is currently a proposal which would grant New York PAs the right to practice medicine independently, without any input or supervision from a physician.

PA: I know, I heard about it. All of my PA colleagues and I think it’s crazy.

You: Yeah, and the assertion that this would alleviate staffing issues has been shown to be false.

Another incorrect assumption is that: “if it’s something serious, a doctor would become involved”, but that actually refers to the current paradigm of physician-led care teams! They don’t understand that if the proposal were to pass: there is no doctor!

PA: Scary! Allowing non-physicians to practice as physicians would be a dangerous and regressive development.

You: Seems that all sensible people agree on this. NYACEP is lobbying hard against it.

PGY-4: I’m about to sign a contract and I’m wondering about malpractice insurance. What happens if I get have a settlement or judgement against me that’s larger than my policy limit?

You: In New York, physicians who meet certain minimum requirements (having hospital privileges, having certain minimum malpractice insurance) are able to participate in the Excess Medical Malpractice Insurance Program. This state funded program provides an additional $1M in back-up coverage in the event a settlement or judgement exceeds your malpractice insurance policy limit. It’s a good thing.

But there is currently a proposal4 which would shift 50% of the cost of this program to doctors, which would cost each participating Emergency Physician $4000-6000 per year (and that’s in addition to what we already pay for our primary policies).

PGY4: That’s terrible! So, essentially my employer would pass that on to me in the form of a lower salary?

You: Yup. NYACEP is lobbying against it.

Same PGY-4: It really seems like New York is a tough place to work from a medical malpractice perspective.

You: Oh yeah, the worst. And if you can believe it, it could get even worse. Get this: There is a proposal5 sponsored by State Senator Hoylman-Sigal and Assemblyperson Lunsford which would extend the statute of limitations to 3 years for malpractice cases and also greatly expand the types of losses that family members can claim when a patient dies, thus vastly increasing the amount of recoverable damages.

PGY-4: So, we’re already the worst and these politicians and trial lawyers lobby trying to make it worse still?

You: Yup. Thankfully, the governor has vetoed this before, but they just keep bringing it back to her.

Hopefully you can find ways to work our legislative agenda into conversation with your colleagues, and when you find it landing on interested ears be sure to invite them to join us for Advocacy Day 2026 (email nyacep@nyacep.org for more information)!

References

- Senator Lanza bill requiring EM physicians to notify prescriber when patient is treated for overdose.

- New York ACEP Supports Hospital Violence Prevention Program

- New York ACEP Opposes The Repeal of the Physician Right to Appeal Claims To Independent Resolution Process

- New York ACEP Opposes Amendments The Physicians Excess Medical Malpractice Program

- New York ACEP Opposes The Wrongful Death Legislation

Practice Management

Joseph Basile, MD MBA FACEP

Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine

Medical Director, Clinical Operations

Staten Island University Hospital

Chair, New York ACEP Practice Management Committee

Sneha Shah, MD

Assistant Medical Director, Department of Emergency Medicine

Assistant Professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine

Maimonides Midwood Community Hospital

Pediatric Readiness for your Emergency Department

Imagine you are working a shift and in the middle of a phone call with a patient’s family member when the triage nurse interrupts you to say, “There’s a coding baby here”. Aside from the panic and fear, what are your initial thoughts and plan? How prepared is your emergency department in caring for a sick child and how does this in turn affect your personal level of comfort in providing this emergent care?

It is no surprise that the more “pediatrics ready” an emergency department is, the better it serves the pediatric population. However, there are varying degrees of readiness among different hospitals nationwide. This encompasses pediatric equipment availability, staff training and comfort in providing care to pediatric patients, pediatric-centered policies and pediatric-specific medications and supplies. This was highlighted in 2006 by what is now the National Academy of Medicine in the “Future of Emergency Care” series. This publication revealed a lack of pediatric resources in both the prehospital and emergency department settings throughout the country. It also highlighted several facts that make these findings even more concerning. One such fact is most children seek emergency care in general hospitals that are not children’s hospitals. These hospitals are known to have less pediatric equipment, expertise and policies when it comes to pediatric emergency medicine. Children also make up close to 30% of all ED visits however only 6% of EDs in the US at the time had all the equipment needed for pediatric emergency care. Based on the findings of this report, their recommendations included establishing pediatric coordinators in both EDs and EMS agencies to make sure the appropriate pediatric equipment, training and processes are in place at each institution, as well as to increase federal funding for the Emergency Medical Services for Children (EMSC) Program.

This led to the establishment of the National Pediatric Readiness Project (NPRP) in 2013. This was a joint collaboration between ACEP, ENA, AAP and the EMSC program. The NPRP focuses on emergency department web-based assessments of pediatric readiness and providing the framework and tools needed to improve pediatric care across all emergency departments nationwide.

One necessary component of this initiative is to establish a pediatric emergency care coordinator (PECC) – a person who serves as the leader for advancing pediatric emergency care within a department or system as well as an advocate for identifying and improving upon any deficiencies that affect pediatric readiness. While identifying a single PECC is often a great start, it is more helpful to establish both a physician and a nurse to serve as PECCs.

In 2015, following the establishment of the NPRP, Dr. Marianne Gausche-Hill, recognized nationally for her research and leadership in both the EMS and PEM worlds, led the publication, “A national assessment of pediatric readiness of emergency departments”. This included an online assessment sent to ED nurse managers nationwide regarding pediatric readiness. Based on an 83% response rate, they noted an overall improvement in ED pediatric readiness compared to prior reports. Contributing factors to higher pediatric readiness assessment scores included the presence of a PECC and was most notable in centers with higher pediatric volumes. Though there was an improvement, it was noted that there were still certain barriers to implementing the guidelines, particularly the cost of training and the lack of educational resources for staff (such as maintaining procedural competency, especially in those EDs with low pediatric volumes).

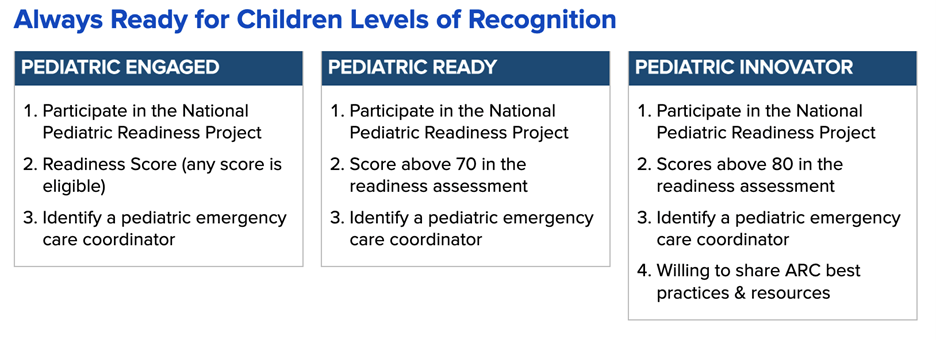

How does this affect us? The New York State Always Ready for Children (ARC) Pediatric Recognition Program, approved in 2023, is a project aimed at recognizing emergency departments focused on improving their pediatric care and establishing standardized titles that help the community and prehospital services best identify the most pediatric-ready hospitals in their area. It was created by the Northeast’s EMS for Children program to establish a more standardized approach to pediatric preparedness in EDs throughout the state, so pediatric patients are less inclined to cross state borders to seek care.

The NYS ARC Program involves establishing a PECC at your institution and submitting an NPRP assessment online and then submitting your NPRP gap report and a commitment letter to the EMSC program. There are 3 designated tiers for recognition: Pediatric Engaged, Pediatric Ready and Pediatric Innovator, with further details for each tier noted on their website (https://www.health.ny.gov/professionals/ems/emsc/always_ready.htm) and on the table below. Regardless of the tier you may start at, this is an important first step in exploring where your specific ED’s pediatric readiness gaps are and evaluating how to close these gaps to ensure the next time you receive a critical pediatric patient, you and your staff can feel confident in your care.

References

- Institute of Medicine; Committee of the Future of Emergency Care in the U.S. Health System. Emergency Care for Children: Growing Pains. National Academy Press; 2006.

- Institute of Medicine (US). Regionalizing Emergency Care: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2010. Appendix C, The Future of Emergency Care: Key Findings and Recommendations from 2006 Study.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK220327/

- Gausche-Hill M, Ely M, Schmuhl P, et al. A National Assessment of Pediatric Readiness of Emergency Departments. JAMA Pediatr.2015;169(6):527–534. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.138

- Remick KE, Hewes HA, Ely M, et al. National Assessment of Pediatric Readiness of US Emergency Departments During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open.2023;6(7):e2321707. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.21707

New York EM Residency Spotlight

Northwell Health Northshore/Long Island Jewish Medical Center

Demographics:

Program Director: Thomas Perera, MD

Program Coordinator: Sandie Luciano

Program Coordinator Email: sluciano@northwell.edu

Hospital Capabilities: STEMI, Stroke, Trauma

Total Number of EM Residents: 69

How many Residents do you train each year: 23

Inaugural Resident Class Year: 2015

Fellowships Offered: Ultrasound, Critical Care, EMS and Disaster (FDNY), Simulation, Global Health, Toxicology, Teaching, Sports, Palliative, Administrative, Ethics, Wilderness, Research, Informatics, Telemedicine, Women’s Health (the first and only EM division for Women’s Health), EM/IM/Critical Care

Benefits Offered: ROSH Review, Lab Coat(s), Discounted Housing, Dental Insurance, Health Insurance, Vision Insurance. Life Insurance, Professional Liability Coverage

Instagram: @zucker_EM

Twitter: @NSLIJ_EM

What is your programs most unique feature?: No program in the country can offer access to a Bioskills procedure lab and advanced Simulation training as we do.

The Bioskills Lab is a fresh frozen cadaver lab which our residents access 3x in orientation month and then 4x yearly, These are freshly dead cadavers whose tissue moves, vessels bleed, and airways are exactly as airways that you will encounter in your clinical practice. Fresh frozen cadavers have been deemed superior to all commercial airway trainers by the American Society of Anesthesiologists and Bioskills is an ideal training solution for procedures of all kinds. We perform regular airway practice including video, surgical airway and fiberoptic, as well as chest tubes, pigtails, lateral canthotomy,, US guided nerve blocks, LPs, IOs, and open thoracotomy. Attendings are charged thousands of dollars for a single training session at Bioskills but our residents have regular access.

While Simulation is common in many training programs, we access a high fidelity Sim center with trained staff and schedule our residents on a series of HALO (High Acuity, Low Occurrence) events and procedures with immediate debrief with our Sim faculty. The monitors, kits, and facilities mirror those we use in our daily practice at Northwell Hospitals. “Train like you fight.”

These two aspects of the program are designed to play off of each other and create the cognitive and technical reflexes that you will rely on for the rest of your career.

What is your favorite aspect of the program?: Our conference is my fave.

Two decades ago we had mandated reducing lecture times such that there is no one hour slot assigned, rotating interactive and small group teaching interspersed with powerpoint offerings, and fostering a culture of high participation but low stakes.

Our faculty attendance at conference is unparalleled. If only 4 attendings show up on a Wednesday morning the residents ask me if it’s ACEP or if our core faculty are lecturing at another program. There are regular case discussions run by a senior resident with a teaching attending in each room. We have a WhatsApp residency discussion called JustinTimeTeaching where residents and attendings share interesting cases, pearls and pitfalls from conference discussion, and ask for advice on tough cases. The more interactive sessions can include standard quiz styles to games that range from HeadsUp, Pictionary, Connections, CodeNames, and more!

What is your program known for?: Ultrasound and Critical Care are heavily emphasized in our program, both in the curriculum and the exposure.

There are 16 US trained faculty who you will work with on shift incorporating POCUS into your practice. ABEM says programs will graduate you if you’ve performed 150 scans. Our residents are required to do 400 recorded and reviewed scans, and they do not struggle to obtain this number. You will be VERY well trained in ultrasound here. An Emergency Dept. US at Northwell IS the official US. No confirmatory studies are done. Our attendings do the scans that send a pt. to the OR, or send a pt. home. Our surgeons and subspecialties accept that the Radiologist will be neither faster, nor better than the ED. That is a level of training you should aspire to, even if you do not do a fellowship.

There are 7 EM/CC trained attendings who will make your time “away” from the ED feel like home. You won’t be an outsider rotating, you will see the attendings you interact with in your home Department. You will have exposure to video reviewed resuscitations and traumas, Level I adult and Pediatric trauma, and ECMO activations. There is also dedicated trauma/ICU time at Maryland Shock Trauma. We have sent residents there for 20 years and are an established presence there, with high expectations for our trainees.

What are you most proud of with your program?: We have been training residents for more than 40 years. We understand that residency is challenging but it shouldn’t be something you are trying to “survive.”

You need to be able to put significant effort and attention to the tasks of developing the skills of an Emergency Physician. Our program is designed to help you do just that. But life will continue, and we understand that as you encounter challenges outside your EM training, a team that has met the challenges of residents for 4 decades is available to you.

We have created a culture of rigor, but also support. Our Emergency Department is a space where residents are respected colleagues and treated as such by staff and consultants.

You are training with your future colleagues and entering residency with your peers, but you are also meeting lifelong friends, mentors, and a support system of alumni that will serve you well for the rest of your lives.

What makes your program an excellent place to complete a residency?: You should be able to drop into ANY Emergency Dept. in the country and be right at home. We can make that happen.

Our program utilizes the resources at Northwell Health, exposure to very high level specialty care for cutting edge resuscitation, and our choice of Emergency Depts. to train you at. We have designed our program as true multi-site training to give you exposure to different practice settings, resources and pt. pathology.

Each of our hospitals serves patients with vastly different socioeconomic characteristics, offering residents the advantage of treating a wide range of patient demographics, both urban and suburban patient populations, and a rich spectrum of pathology. Our emergency medicine residency program emphasizes trauma and critical care management, pediatric exposure, and advanced training in all the subspecialties of emergency medicine. We offer significant trauma training throughout residency at our home level I and II trauma institutions, with an additional trauma month at the free-standing trauma hospital in Baltimore, Maryland at Shock Trauma Center. Residents obtain critical care experience in the Medical ICU, Surgical ICU, Critical Care Unit, Neurosurgical ICU, and Pediatric ICUs. You will also experience community medicine at Huntington Hospital, and a free-standing ED at Lenox Hill Greenwich Village.

We are committed to training residents to become outstanding clinicians and the future leaders in academic and community emergency medicine.

Jeffrey Thompson, MD FACEP

Assistant Professor, Emergency Medicine

SUNY at Buffalo

She Still Wants to Look Pretty

We will call her Chloe. We have all seen her. She is about 30, cachectic, disheveled, toothless, covered in tattoos, some artistic, others – purple pocks dotting her arms, legs and neck – seemingly of her own doing. She sleeps soundly in the bed, arousable, but impossible to keep awake for more than a few seconds. She does not wish to be bothered, but her red, swollen, fluctuant thumb demands attention. Her physical appearance matches the preconception I formed based upon a review of her medical record. She certainly matches the description of one who is homeless, addicted to heroin, suffering from endocarditis and unable or unwilling to follow-through with hospital or outpatient treatment. The management for me will be quick and easy – a few labs, Xray, IV (well, that part won’t be easy), antibiotics and admission.

But I was not prepared for where this encounter would take me. After a futile attempt at obtaining a history, I walked across the room in search of a pair of gloves for an exam. As I donned the gloves, I glanced down and scanned the contents of her clear plastic bag sitting on the chair next to her bed – lipstick, a hairbrush, a pink sash, a small bar of soap and a set of pink press-on fingernails. My initial cynicism convinced me that these were her tools of the trade; and perhaps they were. But as I gazed back and forth between the diminutive, pitiable patient curled up sleeping on the bed and the bag of cosmetics on the chair, I realized that beneath this haggard and faded appearance and beyond the grotesque cartoonish thumb, was a young woman who still cares about her appearance. She still wants to look pretty.

In thinking about this recent encounter, I recalled the television commercials from the 80s and 90s with the young, aspirational kids telling us what they want to be when they grow up, reflecting the hopes and dreams of their afterschool audience; and the narrator’s closing line of “nobody ever says, ‘I want to be a junkie when I grow up.’” Say what you will about the so-called war on drugs; these ads were spot on. I have contrasted Chloe’s ED visit with a recent family gathering where my 4-year-old niece danced around showcasing her hair and “make-up” after using her toy cosmetic kit. The contrast between the two is stark, but I wondered if Chloe ever did the same when she was little. When and how did that transformation occur? Who or what happened to her in the years between being an innocent little girl and a woman whose health and life is ever hanging in the balance? And what hope does she cling to that inspires her to keep buying and applying the lipstick, the nails and the sash?

I perfectly predicted Chloe’s hospital course – admitted for 2 days, IV antibiotics through a PICC line and eventual discharge AMA after she was caught injecting through the PICC. We all know someone like Chloe and it can be disheartening to see her story played out on repeat in our EDs across the state and the country. It is easy to become desensitized and cynical after a few of these encounters and each subsequent patient suffers from our depersonalization and the fatalism we adopt when treating this population. No doubt I began my interaction with Chloe with such an attitude. Yet without saying more than a few words, she reminded me that there is much more to these patients than their drug use, their medical complications and their non-compliance. There is a remnant of hope of something different; something better; something pretty.

Emergency Medicine Resident Committee

Carlton C. Watson, MD MS

Chair, Emergency Medicine Resident Committee

PGY-3

Vassar Brothers Medical Center

Blake A. Peterson, MD MS

Vice Chair, Emergency Medicine Resident Committee

PGY-2

University at Buffalo

Up until this point in my medical training, there has always been a set structure and deadlines: there was a deadline to take the MCAT, a deadline to submit applications to medical school, a set medical student curriculum, a deadline to submit audition rotation applications, a deadline to submit the ERAS application and numerous residency requirements. As my second of three years of residency training quickly comes to a close, I find myself reflecting on “what’s next?” I am entering the first phase of my professional career that has fewer rigid deadlines and it is up to me to make my own structure. With that comes many other questions – Do I want submit a fellowship application or do I apply for jobs? How do I find a job? What kinds of things are important to consider in looking at jobs? As I start this process, there are many points that I am starting to consider as I start the job search.

- Setting. In my training program alone, we rotate through 6 different clinical sites, each with its own “flavor” of emergency medicine. There are large academic centers that are closely aligned with a university or medical school. On the other end of the spectrum, there are more rural emergency departments in resource-scarce areas. If you pursue them, there are fellowships that completely change the nature of your practice such as sports medicine or Emergency Medical Services. There are groups that offer to buy down time for other activities such as administration or other academic pursuits. Combinations of these settings are also possible!

- Resources. Clinically, it is critical to know what kind of supports are available at your hospital and what time of the day or week they are available. When you find yourself caring for a patient with an acute stroke in the middle of the night, what kind of diagnostic testing is available? What kind of specialty services are available? Does your hospital have an agreement with another hospital for transfer? When you document your patient encounter, what kind of electronic medical record do you use? Do you dictate your own notes or utilize a scribe?

- Location. Emergency medicine training teaches a skillset that is respected worldwide. As such, do you want to stay “close to home” or practice somewhere else in the country – or even the world? While attending the 2024 ACEP Council, I found it fascinating that there is a Cruise Ship Medicine Section of ACEP. Now, UCLA even offers a Space Medicine fellowship for emergency medicine residency graduates. The possibilities of location to practice emergency medicine are truly endless!

- Practice Model. Emergency medicine is unique in that there are a number of different practice models. Democratic groups, private groups and corporate groups exist and vary depending on how they are owned and operated. Some emergency medicine physicians are also directly employed by the hospital rather than a group.

- Compensation. For base salary alone, there is a wide range of compensation for emergency medicine jobs. Salary vs. RVU based incomes vary widely as well. Tax forms (W-2, K1, and 1099) can significantly impact the final dollar amount that you bring home. Some practices offer student loan forgiveness or make you personally eligible for the Public Student Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) Program for those with medical student loans. Additional benefits, such as health insurance, malpractice coverage or even CME funds may tip the scale for some!

Applying for any job can feel overwhelming. When applying for a job as an emergency medicine physician in particular, there are many factors to consider. As I approach the end of my residency career, it is imperative to consider these factors. Regardless of where I end up after residency, I have never been more confident in my choice of specialty and I am absolutely privileged to practice emergency medicine.

Education

Sophia Lin, MD FPD-AEMUS

Assistant Professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine and Clinical Pediatrics

Director of Emergency Ultrasound

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medicine

Padmavathi Tipparaju, MD

PGY-2 Resident

Emergency Medicine

Albany Medical Center

Jessica Noonan MD FACEP

Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine

Associate Program Director

Albany Medical Center

Empowering Tomorrow’s Educators: A New Medical Education Selective in Emergency Medicine Residency

One of the many benefits of choosing Emergency Medicine (EM) as a field is the endless fellowship and career options available after residency. From wilderness medicine to pediatrics, practicing EM physicians have the opportunity to seek additional training and incorporate niche career aspirations into their daily practice after graduation. As new subspecialties emerge, many residency training programs have modified their curriculums to increase exposure to as many of these niche areas as possible, so that residents have an opportunity to explore these various career opportunities with ample time before graduation. Between required blocks and selective options, most programs currently expose their trainees to pediatric emergency medicine, EMS, toxicology, ultrasound, critical care and administration. Medical Education (MedEd), has emerged as a vital field dedicated to providing advanced training for the education champions responsible for shaping the next generation of physicians.1 MedEd is a rapidly growing field that remains under-incorporated in many academic medical centers. As of 2020, there were 45 EM MedEd fellowship programs in the United States with 91 fellows that year. Albany Medical Center noticed this deficiency in its curriculum and decided to improve exposure for our residents to the field of MedEd by creating a pilot two-week selective. This selective was developed to provide residents with the opportunity to engage in teaching, mentorship and the development of educational skills.

Goals

The goal of the MedEd selective was twofold: 1) to provide residents with experience serving as an instructor and mentor in a controlled environment and 2) to provide 4th year medical students with focused and in-depth EM teaching in preparation for residency.

The Selective

The two-week selective was offered to PGY-2 residents. It included curriculum development, residency application support and 6 clinical teaching shifts. The curriculum development portion involved creating a 5-minute core content teaching topic based on topics sent in by students prior to shift. The application support portion involved creating a presentation on how to approach the ERAS application. This also included reading personal statements, helping the students navigate the application process and being available for a medical student Q&A session. The 6 clinical teaching shifts provided hands-on experience teaching fourth-year medical students participating in their EM sub-internship. Each teaching shift was divided into two sections: (a) the undifferentiated patient and (b) common EM procedures.2

The undifferentiated patient (3 hours)

Medical students were asked to select 2-3 undifferentiated patients during their shift and were instructed to independently determine “sick” versus “not sick” and then identify the top 5 differential diagnoses along with the relevant diagnostic workup. The MedEd residents would then perform a thorough review of high-yield EM topics related to the chief complaints of these patients, lead discussion and provide feedback on the workup.

The procedure room (1 hour)

Following the clinical experience, residents took the medical students to the procedure room to practice common EM procedures such as ultrasound guided IVs, arterial lines, central lines and chest tubes using practice kits. This one-on-one teaching time allowed residents to slowly walk through these procedures with the students, paying extra attention to highlight tips and tricks they may use during their intern year. Additionally, students had the time to repeat the same procedure on these practice models, thus strengthening their procedural and muscle memory.

Feedback from the Pilot

At the end of each clinical shift, medical students filled out surveys with feedback for further improvements for this pilot program. The surveys revealed that students found these teaching shifts very beneficial to strengthening their EM fundamentals prior to intern year. Students also found that the personalized teaching model created a more comfortable environment to ask questions and privately focus on their personal weak points. The main criticism students expressed was being able to incorporate these shifts earlier on during their sub-internship.

This MedEd selective provided residents with earlier exposure to the academic side of EM. Residents who participated in these teaching shifts completed end of rotation evaluations and reported that they were able to hone their communication skills which is essential in fast paced and high stakes environments of the ED. This selective pushed residents to reflect on their own knowledge, teaching methods and approach to patient care. This self-reflection promoted self-motivation to assess strengths and weaknesses in their own approach to patient care and medical decision-making. Specifically, residents gained the experience of giving and receiving feedback, thereby learning how to provide constructive criticism and mentorship. Additionally, residents were able to develop mentorship skills through ERAS application support. Whether a resident is planning to pursue academics or community medicine, as an attending physician they will be leaders in their field and will need to engage in teaching moments with trainees, advanced practice providers, EMS, patients and families. This selective has the potential to improve patient care, education and communications.

Overall, the Albany Medical Center EM Residency Program successfully incorporated the pilot MedEd selective for PGY2 residents. We hope to ultimately expand upon this success and grow this selective to serve as a positive stepping stone into further developments such as a MedEd Fellowship.

Resources

- Medical education fellowship. Medical Education Fellowship EMRA. (2021). https://www.emra.org/books/fellowship-guide-book/7-education

- Outcome assessment of medical education fellowships in emergency medicine. Jordan J, Ahn J, Diller D, Riddell J, Pedigo R, Tolles J, Gisondi MA. AEM Educ Train. 2021;5:0. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10650

Membership Engagement and Development

Moshe Weizberg, MD FACEP

Medical Director, Emergency Department

Maimonides Midwood Community Hospital

Chair, New York ACEP Professional Development Committee

Interviewer

Lauren Curato, DO FACEP

Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine

Columbia University Irving Medical Center/ NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital

Interviewee

Helen Ouyang, MD MPH

Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine

Columbia University Irving Medical Center

Intro:

I had the pleasure of interviewing Dr. Helen Ouyang, Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. In addition to Emergency Medicine, Dr. Ouyang has expertise in narrative medicine, medical journalism, global and public health. She is currently a contributing writer for the New York Times Magazine and has been published in many distinguished publications including the The New York Times, Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, The New Yorker and Harper’s Magazine, to name a few. Her work has been selected for The Best American Science and Nature Writing 2021 (“State of Emergency”, about New York and Italy’s response to COVID-19 in the NYT Magazine) and was a National Magazine Awards Finalist in 2018 (“Where Healthcare Won’t Go” in Harper’s Magazine). Despite typically being the one telling the story, she is no novice to being interviewed, appearing on BBC, CBS, CNN, C-SPAN, MSNBC, NPR and several podcasts. You can read a selection of Dr. Ouyang’s writings on her website: https://helenouyang.com/ .

Thank you, Dr. Ouyang, for taking the time to speak with NY ACEP!

Curato: Could we begin by asking you to share with us what inspired you to start writing?

Ouyang: I’ve always loved reading and writing and was definitely more of a “humanities person.” I actually decided to go into medicine because of a writing class I took. Dr. Richard Selzer, a surgeon at Yale, wrote a wonderful, but incredibly devastating story about a young surgeon who goes to work in Honduras. We read it in this class I took called “Creative Nonfiction.” I was really struck by the story and it made me want to work overseas. So, I thought to myself, I guess I need to become a doctor too if I want to do that. Little did I know that his writing was actually fiction, which I found out in his obituary many years later.

Curato: How did you become a writer, what was your path?

Ouyang: Still becoming, I think! My undergraduate concentration was in international development studies, so I did a lot of writing in college. But that’s obviously a very different kind of writing from what I’m doing now. I eventually just started doing it and I made many mistakes and learned a lot along the way. I don’t think you can become a writer without actually just starting to do it.

Curato: You’ve written on a range of public health topics, everything from Tuberculosis in Alabama to HIV/AIDS in Pakistan to Bariatric surgery in teenagers and the mental health of airline pilots. What inspires you to pursue a story?

Ouyang: Well, I think the most obvious answer is I write about what interests me. The feature stories I work on take many months. So, I have to be interested in the subject for a long period. Some of it is timing. For instance, hospital-at-home is something I had heard about years ago and I was always interested in learning more about it. But it didn’t really seem like it was ready yet to be a magazine article and I wasn’t sure what the story would really be. But when the pandemic hit and CMS began reimbursing hospital-at-home stays the same as inpatient, I knew this could change how medicine is practiced. Other times, it could just be something I’ve observed in the ED, such as how we treat chronic pain. We don’t really have any good treatments and I often feel like we fail these patients. So, I was intrigued by doctors using virtual reality for it. I think the tuberculosis in Alabama and HIV/AIDS in Pakistan stories you mentioned encapsulates all my interests in global health and on-the-ground reporting and writing. I felt like my past international humanitarian work really helped me with those stories — and of course, I was very drawn to them because of my global health interests.

Curato: … Could you walk us through your process?

Ouyang: Chaotic! I should really try to be less chaotic about it. Unfortunately (or maybe fortunately!) every piece is different, so the process is never identical. Each story is unique depending on the subject, what you get from the reporting and so on. So, there isn’t a one-size-fits-all formula, but I guess that’s what also makes it interesting — and so hard sometimes. Also, the process is very different if I’m writing a reported feature story for a magazine versus an op-ed, a book review or a shorter web piece. For a feature article, I need to have a good story and a greater point — it can’t just be an interesting story without deeper insight into society, medicine or the general state of our world… Nor can it be a topic without any narrative. I spend a lot of time reporting and making sure I have those two things, as well as the access I need, before even deciding to pitch a story.

Curato: To my untrained eye your writing is a blend of investigative reporting, medical journalism and narrative medicine, how would you describe it?

Ouyang: I don’t think each piece I write necessarily always has elements of all three, but I think your observation is probably true of my writing in general.

Curato: I’d imagine there is some overlap between being an Emergency Physician, typically the first doctor to get the patient’s story and being an investigative journalist. Do you feel being an Emergency Doctor has helped your interviewing skills as a journalist or vice versa?

Ouyang: I think they’re really different. When I’m in the ED, it often feels very rushed and I have limited time with patients because another patient or a patient’s family or a resident or nurse needs my attention. And the time I have with each patient is frequently interrupted. When I’m interviewing people, they have my full attention and I can spend as much time with them as they’ll let me. In that sense, that void that I sometimes feel when I don’t get to talk to patients or their families for as long as I would like gets filled when I’m doing reporting.

Curato: You’ve also published on topics directly affecting us as Emergency Physicians, detailing the early days of the COVID Pandemic and opinion pieces on violence in the ED and the criminalization of healthcare workers … do you find it easier or harder to work on these topics that may be viewed as ‘closer to home’?

Ouyang: My impulse is usually to write about others, not myself. I like learning from other people and observing them and telling their stories. I really was resistant to writing about the pandemic. The editors asked and I said no, at first. At the time, I really wanted to write a story about the doctors in Italy and had been corresponding with them already. But then the wave quickly hit us in New York and my resistance to not writing about what was right in front of me became kind of absurd — especially when journalists were having so much trouble getting access to what was actually happening in hospitals. In the end, I’m glad I did write it, to sort of add to the historical records about this extraordinary time in all of our lives — one that hopefully we won’t experience again.

Curato: What advice would you have for emergency physicians who may be interested in similar work?

Ouyang: I have a lot of students and residents ask me that question. My advice is always to become a great doctor first. You only have a certain limited amount of time to train to become an emergency physician. So, focus on that. I didn’t really publish any writing until I had finished training. You have your whole career, your whole life, to write. And there are also so many places where you can write now, like Substack — platforms that didn’t exist a few years ago. So, it depends on what you want to write about and the type of audience you’re looking for. While print journalism is unfortunately becoming more and more limited, other types of online publishing have expanded.

Pediatrics

Maria Tama, MD RDMS

Case

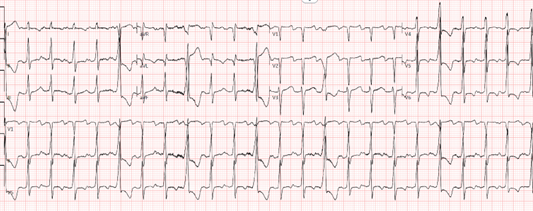

A 13-year-old female with past medical history of anxiety who presented to our pediatric emergency department (PED) with complaints of intermittent reflux and chest pain for 3 days. She denied fever, shortness of breath or syncope, but endorsed cough for two days. On her exam, she was alert, interactive, well-appearing and spoke in full sentences. Initial vital signs were temperature 97.5-degree Fahrenheit, blood pressure 110/77, heart rate 139 beats per minute, respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute and oxygen level 100% on room air. Her cardiac exam was significant for tachycardia with no murmurs or gallops with normal capillary refill and chest wall tenderness on palpation. Her lung exam revealed good air entry with no increase work of breathing and the remainder of her exam was within normal limits.

The patient remained tachycardic after pain medication and aggressive oral hydration. At that point, an electrocardiogram (EKG), chest x-ray and labs were drawn.

EKG revealed sinus tachycardia with premature atrial complexes (PACs). Labs showed an elevated troponin of 122 ng/L, BNP of 7472 pg/mL with mildly elevated LFTS and BUN/creatinine. The chest x-ray showed gross cardiomegaly, the heart silhouette being larger than one half of the thoracic cavity.

Disposition Decision:

Patient remained well appearing in no distress and with good perfusion. Outpatient follow up was briefly considered but repeat vitals showed persistent tachycardia and labs showed minor signs of end organ dysfunction. The decision was made to transfer to a tertiary center for further evaluation and admission.

The Inpatient Course:

At the pediatric cardiac intensive care unit (ICU), she rapidly decompensated. Her echocardiogram showed severe biventricular dysfunction, with a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 15–20%. She was diagnosed with fulminant myocarditis versus newly diagnosed dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM).

Within 48 hours, she required intubation and mechanical ventilation. She was started on inotropes, antiarrhythmics and broad-spectrum antibiotics while awaiting myocarditis workup. Despite aggressive management, she developed cardiogenic shock and worsening fluid overload. The patient underwent placement of an Impella left ventricular assist device (LVAD) to stabilize her. The patient ultimately required orthotopic heart transplantation (OHT) and slowly recovered back to full function. Our patient is currently thriving back at home with a LVEF of 70% and re-engaged in sports and physical activities.

Discussion:

Pediatric myocarditis is an inflammatory condition of the myocardium often triggered by viral infections such as Coxsackie B, adenovirus, parvovirus B19 and more recently, SARS-CoV-2. It typically presents with vague symptoms like chest pain, fatigue, dyspnea or gastrointestinal discomfort, often mimicking benign illnesses and delaying diagnosis.1

In severe or fulminant cases, myocarditis can lead to cardiogenic shock, a critical state of reduced cardiac output and end-organ perfusion. Signs include tachycardia, hypotension, cool extremities, oliguria, and altered mental status.2 These children may require ICU care, inotropes, mechanical ventilation or mechanical circulatory support such as ECMO or LVAD.3,4

If inflammation is prolonged or irreversible, it may evolve into DCM characterized by ventricular dilation and systolic dysfunction. Symptoms include poor feeding, respiratory distress or hepatomegaly. While some patients recover with medical therapy, others may require cardiac transplantation.5

Diagnostic workups include ECG, troponin, BNP, chest X-ray and echocardiogram. Common findings include arrhythmias, cardiomegaly or global hypokinesis.6 Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) is now the gold standard for non-invasive diagnosis, offering high sensitivity for detecting myocardial edema, hyperemia and necrosis. The American Heart Association recommends CMR as a first-line modality in stable patients, often replacing biopsy in early or intermediate presentations.7 A multicenter 2023 study found that early CMR reduced diagnosis time by 40% and avoided biopsy in over half of pediatric cases.8

Endomyocardial biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis but is reserved for refractory or fulminant cases due to procedural risk.9 In unclear presentations, genetic testing can help identify predispositions to cardiomyopathy.10

In multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) secondary to COVID, myocarditis has been reported in up to 17% of patients, often responding well to corticosteroids or IVIG.11 Elevated IL-6 and CRP may predict which patients benefit most from early immunotherapy.12 For virus-positive myocarditis unresponsive to steroids, interferon-beta is being studied in the MYO-VIR trial.13

Lessons in Recognition: When Vitals Don’t Match the Story

This case reinforced a fundamental rule in pediatric emergency medicine:

vital signs are not suggestions, they are critical data points. The patient appeared well, was interactive, afebrile and normotensive. It would have been easy to dismiss her tachycardia as anxiety, pain or other benign causes, but that elevated heart rate was the only suggestion of a brewing cardiac crisis. There were no murmurs, no overt respiratory distress or cyanosis, just a subtle red flag. Recognizing the mismatch between her clinical appearance and vitals led to early cardiology involvement and a timely transfer, ultimately changing her outcome.

Clinical Takeaways

- Persistent or unexplained tachycardia should always prompt further evaluation.

- Myocarditis, though rare, should remain on the differential in pediatric chest pain.

- Early tests like EKG, chest x-ray, troponin and BNP are low-risk and high-yield.

- Vitals are vital for a reason! Do not ignore them and escalate when uncertain.

References

- Law YM, Lal AK, Chen S, et al. Diagnosis and management of myocarditis in children: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2021;144(6):e123–e135. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001001

- Kantor PF, Lougheed J, Dancea A, et al. Presentation, diagnosis, and medical management of heart failure in children: Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29(12):1535–1552. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2013.08.008

- Alexander PMA, Daubeney PEF, Nugent AW, et al. Long-term outcomes of dilated cardiomyopathy diagnosed during childhood: results from a national population-based study of childhood cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2013;128(18):2039–2046. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002767

- Amedro P, Bouvaist H, Sauthier M, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support for fulminant myocarditis in children: a national registry analysis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2023;24(3):215–224. doi:10.1097/PCC.0000000000003153

- Towbin JA, Lowe AM, Colan SD, et al. Incidence, causes, and outcomes of dilated cardiomyopathy in children: results from the Pediatric Cardiomyopathy Registry. Circulation. 2006;113(5):593–598. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.580548

- Lipshultz SE, Law YM, Asante-Korang A, et al. Cardiomyopathy in children: classification and diagnosis. Prog Pediatr Cardiol. 2014;37(1-2):3–12. doi:10.1016/j.ppedcard.2014.10.001

- Ferreira VM, Schulz-Menger J, Holmvang G, et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in nonischemic myocardial inflammation: expert recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(24):3158–3176. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.072

- Esposito A, Curione D, Pedrotti P, et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance in pediatric myocarditis: diagnostic and prognostic value in a multicenter study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2023;25(1):15. doi:10.1186/s12968-023-00967-7

- Cooper LT. Myocarditis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(15):1526–1538. doi:10.1056/NEJMra0800028

- Hinton RB, Ware SM. Heart failure in pediatric patients with genetic cardiomyopathies. Circ Res. 2017;121(7):840–859. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310459

- Belhadjer Z, Méot M, Bajolle F, et al. Acute heart failure in multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) in the context of global SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Circulation. 2020;142(5):429–436. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048360

- Esposito S, Picciolli I, Tagliabue C, et al. Inflammatory biomarkers and treatment response in pediatric myocarditis: insights from a multicenter cohort. Front Pediatr. 2023;11:1030429. doi:10.3389/fped.2023.1030429

- Kühl U, Lassner D, Wallrapp C, et al. Interferon-beta improves survival in patients with biopsy-proven viral myocarditis: a randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2891–2893. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.046

Social Emergency Medicine

Josh Schiller, MD

Director of Global Health/Social Emergency Medicine

Attending Physician

Maimonides Medical Center

Sophia Lin, MD FPD-AEMUS

Assistant Professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine and Clinical Pediatrics

Director of Emergency Ultrasound

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medicine

Women’s Health in Emergency Medicine

Tara Mendola, PhD

WHEM Associate Program Director

Dana Gottlieb, MD

Site Director of LIJMC

WHEM Fellowship Associate Program Director

Jessica Army, MD

Women’s Health in EM Division Chief

WHEM Fellowship Program Director

Can you tell us about the Women’s Health in Emergency Medicine (WHEM) Fellowship and how it is relevant to EM practice?

The Women’s Health in Emergency Medicine (WHEM) Fellowship is a two-year fellowship designed to integrate comprehensive women’s healthcare into emergency medicine practice. This fellowship aims to equip emergency medicine (EM) physicians with the knowledge and skills to address the unique health concerns of female patients, thereby enhancing patient care and outcomes. Further, the fellowship has a strong advocacy and policy component, empowering fellows to become changemakers in the field.

How could WHEM be able to provide for your patient communities?

WHEM works to increase provider awareness of gendered care disparities in the ED and increase the availability of education and resources to eliminate those disparities. While we aim to improve clinical management of female patients, we are also working to improve our warm handoffs to social services such as Public Health Solutions Family Support Program, which provides a comprehensive package of services to pregnant and parenting families in NYC.

Are there certain age groups that could be particularly affected by this Fellowship?

All ages are touched by the fellowship program. However, each fellow will specialize in an area of women’s health in the ED, such as cardiology, neurology or reproductive health. Our inaugural fellow Dr. Alexadra Over, will concentrate on the intersection of social EM and women’s health in the ED.

How did the development of WHEM come about?

WHEM came about in 2024. Jessica Army, MD, had been working for four years to get a miscarriage management protocol approved and Dana Gottlieb, MD, led SANE/SAFE initiatives at Long Island Jewish Medical Center. Army and Gottlieb met T.S. Mendola, PhD, a new faculty hire specializing in reproductive health policy. Together, they decided a Division of Women’s Health in Emergency Medicine would provide an institutional home to leverage their collective goals into action.

When creating successful programming, how important is collaboration with other institutions locally? What specific institutions have you found instrumental?

Collaboration is essential to collective power and policy change. Externally, we partner with Access Bridge, FemInEm and Public Health Solutions. We maintain open communication with our local Planned Parenthood for referrals. Internally, we are proud to be supported by the Katz Institute of Women’s Health and our OBGYN department. We also partner with Zucker Hillside Hospital to strengthen our referrals of women with substance use disorders. However, we want to stress that we are less than one year old! More collaborations are in the works.

How is WHEM presented/taught to other staff/resident in your department?

We publicize our events through newsletters and emails to the department and hold a monthly journal club to address different issues touched by our Division’s mission. We also maintain a public-facing website, womenshealthem.com. In all of our materials, we adhere to WHEM’s mission to provide the highest quality care possible to women and girls in our EDs. We will also be hosting our 4th annual Women’s Spring Conference this year on April 23, 2025 at the Feinstein Institutes for Medical Research. This year’s annual theme is Reproductive Care in the ED.

What are common challenges encountered with WHEM? How are they overcome?

The biggest challenge we face is sustainable funding. Neither women’s health nor emergency medicine have ever had their own NIH institute, making it a double challenge to secure multi-year research and service grants to support long term clinical and research initiatives at scale. The second biggest challenge is simply navigating the current federal funding landscape, where recent anti-DEI trends make obtaining funding to study gendered disparities challenging.

What advice can you offer to EM physicians interested in initiating a similar program to WHEM but who have no background or training in this field? What are the first steps they can take to pursue this interest?

Start small: choose one thing about women’s health in your ED that you feel could be improved upon. Find the issue in your ED that gets you up in the morning and start asking, why can’t we change this? Ask questions, then ask more questions. Don’t take “no” or “we can’t do that” for an answer. Organize with your fellow physicians and nurses: you are stronger together. Reach out to other institutions doing similar work and ask for mentorship. You would be surprised at how willing people are to help. And then see how far you can go.

Please provide any concluding thoughts on how you see the ER being a conduit for the study of Women’s Health.

The Emergency Department is a unique landscape that becomes a point of refuge for patients who lack care elsewhere or may not feel safe seeking care elsewhere. Like many demographics, women find themselves seeking care in the ED for a myriad of complaints. Until recent decades, they weren’t even represented in the foundational studies to guide that care—and today, the mandate to include women in clinical trials hangs in the balance with uncertain federal guidance. Emergency Medicine, as a newer specialty with a broad patient population, is well positioned to study the needs of our patients and roll out new protocols to expand our access to women’s specific care needs. This includes improved diagnostic testing, protocols, and anticipation of needs for follow-up care.