New York ACEP Updates

Jeffrey S. Rabrich, DO MBA FACEP FAEMS

Senior Vice President

Envision Physician Services

New York ACEP is Advocating For You

I hope everyone is enjoying the nice Fall weather and our vibrant foliage across New York State. The NYACEP leadership team and councilors have just returned from the ACEP Council meeting and Scientific Assembly in Las Vegas, NV. I would like to take a moment to thank all our Councilors who donated their time and expertise to participate and advocate on behalf of all NYACEP members. As the second largest chapter in the country (California still has us beat by a couple hundred members) we had 30 councilors who were able to debate resolutions, vote for the ACEP President-Elect and Board. For those that may not be familiar with the Council and how it operates, if you search prior issues of EPIC there have been a few very good articles written by New York Councilors on their experiences. Essentially, the council is how the business of the college gets done. In addition to voting for board members, council vice-speaker and president-elect, the council sets the agenda and direction of the college by debating and passing resolutions on a variety of topics that affect our practice of emergency medicine. NYACEP sponsored or co-sponsored several resolutions this year. One such resolution was related to consideration of boarding and crowding in case reviews such as root cause analysis and directs ACEP to work with Joint Commission and other relevant organizations to incorporate this into hospital practices. Another one of our resolutions dealt with PHI and providing education around appropriate sharing of relevant information with other healthcare providers. Have you even had a patient who presents with abdominal pain and was just seen at the ED down the road and had a CT but when you call that ED they say “sorry, HIPAA-I can’t tell you the results”? This adopted resolution will lead to improved educational materials and guidelines so this doesn’t happen as frequently. Other resolutions addressed alarm fatigue and workplace violence. The final resolution I want to talk about is an example of how something that happened in New York can be brought to National’s attention and help leverage their resources. As many will recall, the NYS DOH implemented mandatory screenings most recently for Hepatitis C but previously for HIV as well and there was no discussion with the EM community for either and we ended up with unfunded mandates and regulation that are hard to meet. Resolution 54 this year, submitted by NYACEP, requires ACEP to work with relevant stakeholders including state health departments to ensure adequate resources and funding for required public health screenings as well as processes that ensure these screenings are not delaying or distracting from the ED’s primary mission and immediate lifesaving care.

Now that we have returned from ACEP, we are turning our attention the remaining issues from the prior legislative session, most importantly ensuring the governor vetoes the Wrongful Death Bill which will be on her desk soon. We will need your help in speaking out by responding to the action alerts we send out. Additionally, we are working with the bill sponsors of the workplace violence prevention bill we were able to have some success with last year so we can get it introduced again this upcoming session and hopefully get it passed.

Do these things sound interesting to you? Do you wish things about your practice and work experience would change? If so, come help us effect change in New York. NYACEP has several committees and programs that could use new members with new ideas, energy and interest. Not sure? Come attend a committee meeting or board meeting and see what you think. Check it all out on our newly redesigned website. Wishing everyone a very happy and safe upcoming holiday season.

Sound Rounds

Thomas M. Kennedy, MD

Assistant Professor of Pediatrics in Emergency Medicine

Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

Department of Emergency Medicine, Division of Emergency Ultrasound

NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital

John Paolo Palad, MD (PGY-2)

Department of Emergency Medicine

Staten Island University Hospital

Eli Azrak, DO (PGY-1)

Department of Emergency Medicine

Staten Island University Hospital

Eye Spy: Point-of-Care Ultrasound for Ocular Trauma

Case

A 7-year-old male with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department (ED) with vision loss in his right eye. History obtained from his parents was pertinent for the patient’s eyes deviating laterally for several days prior to presentation. Two weeks ago, the patient was forcefully hit by a person’s hand while playing soccer. The patient initially was asymptomatic until a few days ago when he developed complaints of vision changes and eye deviation.

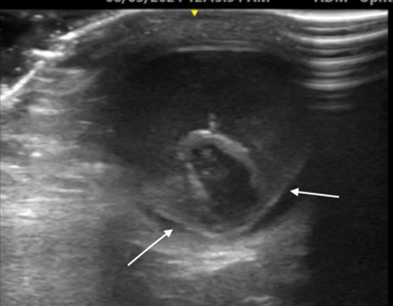

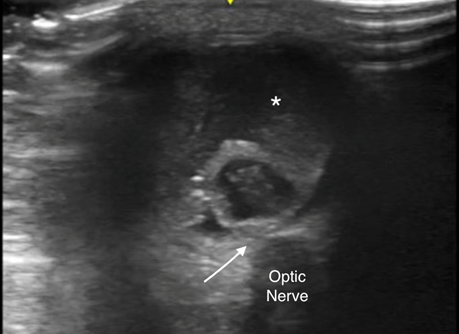

Upon arrival to the ED, his vital signs were within normal limits. Physical examination revealed a well appearing child in no distress with an atraumatic, normocephalic head, his pupils were equally round and reactive to light and accommodation and his extraocular movements were intact without diplopia. When the left eye was covered, the right eye began to deviate laterally. Visual acuity was 20/20 in the unaffected eye. In the affected eye, he was able to see light but had no clear vision except in the extreme temporal visual field. The emergency medicine (EM) physician was unable to visualize the fundus or the light reflex of the affected eye. Intraocular pressure was 14 mmHg in both eyes. Ocular point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) was performed to evaluate the acute vision loss (Figures 1 and 2).

Discussion

Retinal detachment in the pediatric population is relatively uncommon, accounting for 0.38-0.69 per 100,000 population.1 It is an ophthalmologic emergency that requires prompt recognition by EM physicians. The most common causes of retinal detachment are trauma, congenital or developmental anomalies (e.g., Marfan syndrome, retinopathy of prematurity), high myopia and infections.2 True vision loss in pediatric patients can be difficult to assess due to patient cooperation, so close attention to the focused history and physical examination findings is necessary. Concerning examination findings include a diminished red reflex, abnormal visual acuity using a Snellen chart or picture cards, or various abnormalities on fundoscopic examination such as, but not limited to, elevation of the retina, an unfocused retina or a pigmented line delineating the detachment.

POCUS can be used to evaluate for ocular pathology. On ultrasound, a retinal detachment typically appears as a thin, linear, highly reflective membrane floating or undulating within the vitreous cavity. In a normal eye, the retina is firmly attached to the back of the eye and should not be visible on ultrasound. When detached, the retina separates from the underlying layers and may create a characteristic V- or funnel-shaped appearance, with the apex pointing toward the optic nerve as seen in Figure 1. Kim and colleagues found the sensitivity and specificity of POCUS for detecting retinal detachment to be 75% (95% CI: 48-93%) and 94% (95% CI 87-98%), respectively.3 Additionally, the positive likelihood ratio was 12.4 (95% CI: 5.4-28.3) and the negative likelihood ratio was 0.27 (95% CI: 0.11-0.62). It is necessary for EM physicians to identify retinal detachments, as they require urgent consultation with an Ophthalmologist and typically need operative management.4

Vitreous hemorrhage is more common than retinal detachment. This is primarily because vitreous hemorrhages can arise from a broader range of causes such as congenital, vascular, ocular inflammation/infections, tumors and systemic associations.5 On ultrasound, a vitreous hemorrhage appears as echogenic (bright) specks or opacities within the normally anechoic (dark) vitreous cavity. Unlike the clear, uniform appearance of normal vitreous, a hemorrhage disrupts this with varying degrees of reflectivity depending on the amount and density of blood. The hemorrhage is often mobile and may shift or swirl as the patient moves his or her eye, which is a characteristic feature referred to as the “washing machine sign.” For the diagnosis of a vitreous hemorrhage, the sensitivity of POCUS is 81.9% (95% CI: 63-92.4%) and the specificity is 82.3% (95% CI: 75.4-87.5%).6

ED management should consider the use of an eye shield, educate the patient to avoid physical activity and avoid prescribing eye drops that will constrict or dilate the pupil which could further worsen the condition. Treating the underlying cause should be considered and refer the patient to an Ophthalmologist for further care. Close follow-up is needed to ensure resolution of the hemorrhage. Operative management may occur depending on if the hemorrhage persists and its severity.

Case Conclusion

This patient required two procedures by the Ophthalmology service. He had a vitrectomy performed and several weeks later, a pars plana vitrectomy where vitreous humor and scar tissue were removed and the retinal detachment was treated. In addition, the patient also required intravitreal methotrexate injections. He is currently still under management and close follow-up for his visual complaints.

Indications

- Acute eye pain

- Ocular trauma

- Suspected increased intracranial pressure

- Suspected intraocular foreign body

- Vision change or loss

Technique

- Lay the patient supine or at a 45-degree angle.

- Place a piece of Tegaderm over the closed eye with a generous amount of ultrasound gel on top of it.

- Use a high-frequency linear probe and hold it with the first 3 fingers of your hand while placing the 4th and 5th fingers on the patient’s nose or orbital rim for support.

- Evaluate the posterior chamber by fanning through the eye in both sagittal and transverse planes with the gain (brightness) up high.

Pitfalls and Limitations

- A contraindication for ocular POCUS is suspected globe rupture because the pressure applied from the probe onto the eye can result in loss of vitreous humor.

- Vitreous hemorrhage can be easily missed if the gain of the image is low. Keep the gain high to ensure adequate visualization of the posterior chamber.

- Not using the ocular presets on the ultrasound machine to minimize the mechanical index and thermal index fails to adhere to the as low as reasonably achievable principle.7

References

-

- Gan NY, Lam WC. Retinal detachments in the pediatric population. Taiwan J Ophthalmology. 2018; 8(4):222-236.

- Haimann MH, Burton TC, Brown CK. Epidemiology of retinal detachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1982; 100(2):289-292.

- Kim DJ, Francispragasam M, Docherty G, et al. Test characteristics of point-of-care ultrasound for the diagnosis of retinal detachment in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2019; 26(1):16-22.

- Read SP, Aziz HA, Kuriyan A, et al. Retinal detachment surgery in a pediatric population: visual and anatomic outcomes. Retina. 2018; 38(7):1393-1402.

- Lahham S, Shniter I, Thompson M, et al. Point-of-care ultrasonography in the diagnosis of retinal detachment, vitreous hemorrhage, and vitreous detachment in the emergency department. JAMA Netw Open. 2019; 2(4):e192162.

- Naik AU, Rishi E, Rishi P. Pediatric vitreous hemorrhage: a narrative review. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2019; 67(6):732-739.

- AIUM official statement for recommended maximum scanning times for displayed thermal index values. J Ultrasound Med. 2023; 42(12):E74-E75.

EMS

David Lobel, MD FAEMS FACEP

Clinical Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine,

State University of New York Downstate Medical Center

Medical Director, Prehospital Services

Department of Emergency Medicine, Maimonides Medical Center

Mackenzie Wilson, MD

PGY-2 Emergency Medicine

Maimonides Medical Center

Keeping Our Providers Safe

Violence directed at health care providers has become increasingly prevalent, with an ACEP Emergency Department Poll from 2022 reporting that as many as 55% of the physician respondents and 70% of emergency department nurse respondents have experienced workplace violence. In the prehospital setting, where environments are less controlled and cases more unpredictable, EMTs and paramedics are at an even higher risk of danger, with the US Bureau of Labor Statistics finding that EMS personnel are six times more likely than the general US population and 60% more likely than in-hospital providers to experience a risk of lost-time injury. Further, studies measuring career prevalence have demonstrated that an alarming 57 to 93 percent of EMS responders having experienced at least one act of verbal and/or physical violence during their career.

Violence towards EMS is felt personally in the New York City area when we hear the names of providers such as Yadira Arroyo, an EMT who was murdered while on duty in the Bronx in 2017, and Lieutenant Alison Russo-Elling, who was stabbed to death in Queens while on a break. In deference to the violence against prehospital providers, New York City has passed legislation requiring the Fire Department Commissioner to provide anti-ballistic and stab resistant body armor for employees who provide emergency medical services. This article intends to address several of the issues that arise with the institution of body armor for emergency care providers.

Cost. Cost is an issue for every aspect of prehospital care. As 911 call volumes continue to rise, particularly in urban areas, resource allocation and budgeting are very real concerns when it comes to the implementation of new equipment. For those of us who spend time working with EMS, we know that each choice matters – if we invest in an automated CPR device it might be at the cost of implementing video laryngoscopy or foregoing the top dollar medications we would like to have available. As it pertains to body armor, a single NIJ IIIA grade vest is available commercially for upwards of $700. Outfitting thousands of providers with these vests will require immense funding- but hopefully with the priceless benefit of lives saved.

Comfort. Comfort is an issue with regards to the weight and physical demands of carrying the equipment but is also a concern for thermoregulation and agility while performing medical procedures. Most commercially available vests weigh less than 10 pounds but likely will still require providers to have specific training and practice with performing daily field tasks while wearing armor. Comfort may be a particularly salient issue with regard to use – asking a provider to wear an uncomfortable garment for the duration of the shift will certainly result in non-compliance, therefore mankind the aforementioned cost-benefit debacle less productive.

Along with comfort is the consideration of when body armor should be worn. Lightweight vests that can be worn underneath the uniform will no doubt be worn throughout the shift but heavier gear may carry with it the temptation to don and doff between calls, therefore potentially reducing compliance. Public appearance also plays a roll; in an age of widespread social media use and common filming of providers, civilians may find EMTs visibly donning body armor alarming, leaving the door open for scrutiny and distrust.

Choosing the right product. Choosing the right product for the setting is essential to optimize protection. The National Institute of Justice rates anti-ballistic vests from Type I, which is effective against small caliber weapons, to type IV, which is designed for protection from armor piercing munitions. The between levels include II-A, which is generally accepted by many law enforcement agencies as a bare minimum standard, and type III-A, which will withstand the 44 Magnum for anyone choosing to confront Dirty Harry. Higher levels come with greater degrees of protection but also with increased cost and bulk.

Knowing your equipment and its limitations. It is important the prehospital providers be familiar with the type of equipment provided, the types of weapons it can and cannot withstand, and its points of vulnerability. It is also essential to be aware of any physical limitations the equipment might put on the provider and is therefore advisable to train with the equipment so that those limitations don’t become apparent in the midst of a time sensitive medical intervention.

Stay safe. It is essential that our civilian providers in the community understand that no body armor is impenetrable and the use of it is not a substitute for active situational awareness and scene safety measures. The armor is an added level of protection but general tenets of scene safety need to be addressed as they would otherwise be. A prehospital provider with body armor should not perform as a member of a tactical team until they have been educated in tactical procedures and completed field training with an assigned team. Visible body armor should clearly identify the wearer as medical personnel, lest they be considered combatants/law enforcement officers and become a target of aggression. Visible body armor that suggests that the provider may be affiliated with law enforcement may also be a hindrance to the patient allowing care to be provided, particularly in cases where criminal activity is involved or immigration status is an issue.

Durability and sanitization. Body armor, like all medical equipment and medications, has a shelf life and with use will require replacement. For most manufactures, this life-span is approximately 5 years. Additionally, unlike the body armor used by law enforcement, body armor used by EMS will be frequently exposed to body fluids and blood borne pathogens, which will require sanitization considerations. Most guidelines for care are clear that these devices are not machine washable, should not be dry cleaned and should not be exposed to chemicals or deodorizing sprays. The authors recommend consultation with the product manufacturer prior to using sanitizing agents when creating protocols for sanitization that do not compromise the integrity of the body armor.

Training and policy. As with any device introduced into the prehospital setting, body armor should be introduced with proper in-service explaining how and when the device is intended to be used, as well as how to maintain the device and detect when it needs maintenance or replacement. This should be backed by a clearly written policy describing the previously listed parameters. Clear, effective training and policy is the best way to ensure compliance and therefore, safety.

Conclusions. Healthcare providers in general are increasingly subject to workplace violence and our first responders deserve the best protection we can offer them. Implementation of body armor in a civilian EMS system should include proper education about the equipment being issued, including its strengths and weaknesses, how to use it, when to use it, how to maintain it and when to replace it. Clear and well documented policy and procedure should be included in the implementation process. Finally, this is a new chapter for many EMS systems and a prime opportunity to collect data to help refine and redefine the future of this equipment in the prehospital setting.

References:

-

- https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1048291119893388

- EMS Body Armor: What Providers Need to Know, EMS 1 published May 18, 2016; David K. Tan MD, EMT-T, FAEMS

- https://safelifedefense.com/shop-category/body-armor/

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.3109/10903127.2015.1128029

- Thomsen TW, Sayah AJ, Eckstein M, Hutson HR. Emergency medical services providers and weapons in the prehospital setting. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2000 Jul-Sep;4(3):209-16. doi: 10.1080/10903120090941218. PMID: 10895914.

- Maguire, B.J.; Al Amiry, A.; O’Neill, B.J. Occupational Injuries and Illnesses among Paramedicine Clinicians: Analyses of US Department of Labor Data (2010–2020). Prehospital Disaster Med. 2023, 38, 581–588.

-

- Mausz J, Piquette D, Bradford R, Johnston M, Batt AM, Donnelly EA. Hazard Flagging as a Risk Mitigation Strategy for Violence against Emergency Medical Services. Healthcare. 2024; 12(9):909. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare12090909

-

- Evarts B. Fire loss in the United States during 2017, https://www.nfpa.org/-/media/Files/News-and-Research/Fire-statistics-and-reports/US-Fire-Problem/osFireLoss.pdf

- https://local2507.com/nyc-ems-responded-to-record-number-of-911-calls-in-2023-union/

- Model policies to protect US fire-based EMS responders from workplace stress and violence; New Solut 2022 Aug;32(2):119-131 doi: 10.1177/10482911221085728. Epub 2022 Mar 24. Jennifer A Taylor 1, Regan M Murray 2, Andrea L Davis 1, Sherry Brandt-Rauf 1, Joseph A Allen 3, Robert Borse 4, Diane Pellechia 5, David Picone 6

Abbas Husain, MD FACEP

Associate Residency Director

Medical Education Fellowship Director

Staten Island University Hospital, Northwell Health

Amar Bukvic, DO

PGY-1

Staten Island University Hospital, Northwell Health

A Matter of Life and Death: The Role of the EM Physician in Goals of Care (GOC) Discussions

The ED: Where It Starts

As EM physicians, we are versatile— suturing with the precision of a plastic surgeon or interpreting images like a radiologist. We take pride in managing a broad range of critical conditions that demand proficiency in skills across multiple specialties. Yet, despite caring for some of the sickest patients in the hospital, there is one specialty we often overlook: palliative medicine.

Emergency departments are not designed for goals-of-life conversations. Between overcrowding from boarding and the constant pressure for productivity, it is nearly impossible to find the time or space for delicate discussions about life and death. In spite of these challenges, there is an undeniable need for end-of-life care to begin with us. More than 50% of patients in their final month of life will visit the ED, most of them are admitted and pass away in the hospital.1

Our Role in Establishing, Guiding, and “Dispo-ing” Goals of Care

The role of the EM physician should not be to replace the palliative care team but to add components of palliative medicine that are within our scope. Just as we manage a shoulder dislocation in the absence of orthopedics, we should initiate palliative conversations when appropriate, understanding that deeper, ongoing management can later involve a specialized team.

The Who

From the healthy young adult that suffers a non-recoverable accident to the older patient having an acute exacerbation of a chronic disease, the people we see regularly are the ones that see us first, and sometimes, last.

EM physicians are exceptionally positioned to detect “sick” vs. “not sick”. A multitude of EM specific algorithms for palliative care discussion exists. One of the simplest ways to determine this is the “surprise question” which is “would you be surprised if this patient died in the next 12 months?” If the answer is no, the positive predictive value of death was 0.92 with a specificity and sensitivity of 79% and 68%.2 This provides a very easy screening tool for a busy EM physician to use to stratify which patient would benefit from GOC discussions.

The Why

EM physicians are perfectly positioned to be the “first responder” of palliative care. GOC intervention in the ED has been shown to increase the quality of life for patients as measured by the FACT-G (Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General Measure) score. 3 It also does not seem to shorten survival, increases overall patient satisfaction, and increases advanced directive documentation within the electronic medical record.4 The positive effect on the patient has been shown but there is also a positive effect on the system as a whole with a decrease in subsequent visits.4

Futile treatment also has an effect on us. The leading cause of burnout within EM physicians has been shown to be emotional exhaustion and depersonalization.5 A meta-analysis of ICU physicians and nurses showed that futile life-sustaining treatment had a profound effect on them emotionally causing negative emotions like anger, depression, and soul-destroying sentiments.6 Reducing the amount of futile care provided in the ED can help alleviate the emotional burden of intensive, non-sustainable resuscitation efforts.

The How

End of life conversations are never easy but can be standardized. The SPIKES model was developed by medical oncologists to provide a framework for sharing unfavorable medical information.7 It stands for setting, perception, invitation, knowledge, emotion, and strategy. Setting establishes a time and place. Perception is asking questions before telling information. Invitation is asking if the patient and family are ready to talk. Knowledge is providing your expertise on the situation in simple terms. Emotion is addressing emotion with empathy via naming, understanding, respecting, and supporting. Strategy is to formulate the next steps or providing the possible pathways the patient will go through.

Another aspect is understanding the acute symptomatic needs of a dying patient. This can be accomplished through further training in palliative medicine with your palliative colleagues. Briefly, we can discuss some important considerations here. Pain is present in nearly 40% of patients at the end of life.8 Pain can be managed with 2-5 mg IV morphine every 15 minutes as needed, which also relieves dyspnea without causing undue sedation.8 Lastly, the “death rattle”, terminal respiratory secretions, are usually managed by pharmaceutical agents like glycopyrrolate. However, it has been shown that addressing pain and dyspnea are superior as medications had no greater effect than placebo on reducing secretions.9

The ED: Where It Ends

The scope of emergency medicine continues to expand as we broaden the concept of emergency care and care delivery. Palliative care is an excellent addition to our arsenal of skills within the ED. Even a brief 2-hour educational intervention can increase EM physician comfort levels in discussing goals of care.10 Through quick stratification strategies like the “surprise question”, standardized conversations using the SPIKES framework, and proper symptomatic management, we have the potential to reduce the emotional toll on the patient, their family, and ourselves. As EM physicians, we are uniquely positioned not only to initiate life-saving interventions but also to ensure a dignified end when those interventions are no longer appropriate.

References

-

- Smith AK, McCarthy E, Weber E, et al. Half of older Americans seen in emergency department in last month of life; most admitted to hospital, and many die there. Health Aff. 2012;31(6): 1277-1285.

- Downar, J., Goldman, R., Pinto, R., Englesakis, M., & Adhikari, N. K. (2017). The “surprise question” for predicting death in seriously ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l’Association medicale canadienne, 189(13), E484–E493. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.160775

- Grudzen CR, Richardson LD, Johnson PN, et al. Emergency Department–Initiated Palliative Care in Advanced Cancer: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(5):591–598. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.5252

- Bigelow S, Medzon R, Siegel M, Jin R. Difficult Conversations: Outcomes of Emergency Department Nurse-Directed Goals-of-Care Discussions. J Palliat Care. 2024 Jan;39(1):3-12. doi: 10.1177/08258597221149402. Epub 2023 Jan 2. PMID: 36594209.

- Zhang Q, Mu MC, He Y, Cai ZL, Li ZC. Burnout in emergency medicine physicians: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020 Aug 7;99(32):e21462. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021462. PMID: 32769876; PMCID: PMC7593073.

- Choi HR, Ho MH, Lin CC. Futile life-sustaining treatment in the intensive care unit – nurse and physician experiences: meta-synthesis. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2024 Feb 21;14(1):36-46. doi: 10.1136/spcare-2023-004640. PMID: 38050047.

- Bell, D., Ruttenberg, M. B., & Chai, E. (2018). Care of Geriatric Patients with Advanced Illnesses and End-of-Life Needs in the Emergency Department. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine, 34(3), 453–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cger.2018.04.008

- Blinderman CD, Billings JA. Comfort care for patients dying in the hospital. N Engl J Med 2015;373(26):2549–61.

- Wee B, Hillier R. Interventions for noisy breathing in patients near to death. Co chrane Database Syst Rev 2008;(1):CD005177.

- Bowman, J. K., Aaronson, E. L., George, N. R., Cole, C. A., & Ouchi, K. (2018). Effect of Brief Educational Intervention on Emergency Medicine Resident Physicians’ Comfort with Goals-of-Care Conversations. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 21(10), 1378–1379. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2018.0217

Research

Laura Melville, MD MS

Associate Research Director

SAFE Medical Director

NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital

Chair, New York Research Committee

Kassem Michael Makki, DO

Chief Resident of Research

NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital

Christopher Mendoza, MD MA FACEP

Vice Chief of Clinical Services

Director of Quality and Patient Safety

Assistant Professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine

Department of Emergency Medicine

NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital

Longitudinal Care Plans for High Utilizers in the Emergency Department

Introduction

High utilizers of the emergency department (ED) represent a small yet significant portion of the patient population. Despite them accounting for a small percentage of the over ED patient population, their frequent visits and high resource needs have a large impact on ED through put and the care of other patients. Also referred to as super-high utilizers (SHUs), these patients frequently return to the ED due to chronic medical conditions, complex social needs and other underlying factors1. SHUs often experience fragmented care, which can result in inefficient resource use and suboptimal health outcomes. One approach to addressing these challenges is the development of longitudinal care plans (LCPs), which aim to provide continuous, coordinated care across healthcare settings1. This article explores the development, implementation and outcomes of LCPs for managing SHUs in the ED setting.

Indications for Longitudinal Care Plans

Longitudinal care plans are particularly useful for patients who present to the ED frequently due to a combination of chronic health conditions, psychiatric disorders and unmet social needs. SHUs often suffer from complex conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), psychiatric disorders and substance use disorders1,2. Social determinants of health, such as housing instability and lack of access to primary care, exacerbate these issues and lead to recurrent ED visits. LCPs are designed to address both medical and social needs, creating a coordinated system of care that aims to reduce the frequency of ED visits2.

Demographics of Super-High Utilizers

A retrospective cohort study of 1,515 super-utilizers admitted to an urban safety-net hospital provided insight into the demographic characteristics of this patient group3. The mean age was 53.8 years, with 44.2% of the population being homeless. In terms of race and ethnicity, 40.4% identified as Hispanic/Latino, 37.6% as White, 17.3% as Black and 1.5% as Asian. Males made up 54.9% of the population, while females comprised 45.1%. A large proportion of SHUs (56.6%) were covered by Medicaid and 21% were on Medicare, indicating a significant reliance on public health insurance programs. Understanding these demographic factors is essential for developing effective and tailored LCPs. The LCPs facilitate efficient up front communication to the care team, explaining the complicated nature of these patients care needs, allowing for more focused and expedited care.

Impact on Healthcare Utilization

The financial burden associated with SHUs is substantial, particularly in cases where patients have chronic conditions such as sickle cell disease (SCD). A study on healthcare expenditures found that super-utilizers with SCD had healthcare costs that were 13.37 to 43.46 times higher than those of low-utilizers, depending on their insurance type4. These patients incurred significant costs in both inpatient and outpatient settings, as well as through frequent ED visits. This pattern of high healthcare utilization underscores the importance of implementing LCPs to reduce unnecessary ED visits and hospital admissions. Moreover, SHUs are often readmitted multiple times per year, which places a strain on ED resources, increases wait times and contributes to the overcrowding of hospitals. LCPs aim to mitigate these issues by addressing the root causes of frequent ED use, such as unmanaged chronic diseases and lack of access to primary care.

Components of Longitudinal Care Plans

LCPs are comprehensive, patient-centered plans that span across various healthcare settings. They aim to reduce unnecessary ED visits, improve chronic disease management and enhance overall patient outcomes. The following components are essential in the development and implementation of LCPs:

- Multidisciplinary Team Approach: LCPs require the collaboration of a diverse team of healthcare providers, including ED physicians, primary care providers, security personnel, social workers, case managers and psychiatrists1. This team works together to assess the patient’s medical, social and psychiatric needs and create a plan that addresses these factors comprehensively.

- Patient-Centered Goals: LCPs are designed around the patient’s individual health goals, focusing on improving their quality of life while managing chronic conditions. The care plan coordinates efforts between the ED, inpatient services, outpatient providers and primary care to ensure that all aspects of the patient’s health are addressed2.

- Ongoing Communication: Real-time updates and alerts during ED visits or hospital admissions are critical to keeping the care team informed about the patient’s status and any changes in their health1. This continuous communication ensures that the care plan is updated and adjusted as needed, based on the patient’s evolving needs.

- Social Support Integration: A key element of LCPs is addressing the social determinants of health that often drive SHU behaviors, such as homelessness, substance use disorders or lack of transportation. LCPs coordinate with community resources to help meet these needs, ultimately reducing the reliance on the ED for non-emergent care.

- Combating implicit bias: Often these patients present secondary to exacerbation of chronic medical conditions. Often due to non-compliance and difficult access to care. This is a strain on the ED and often the ED provider. The care plans can serve as a way of explaining the social situation of the patient up front, ideally curbing some of the implicit bias felt by the provider. They aim to help the provider better understand the patient and his or her needs, which can help make for a productive initial interaction.

Steps in Developing a Longitudinal Care Plan

Creating an effective LCP involves several key steps that ensure the plan is comprehensive and tailored to the patient’s unique needs:

- Identification: The first step is identifying patients who qualify for an LCP. This typically involves tracking patients with frequent ED visits and hospital admissions, who often have complex medical and social needs. Frontline ED providers will also be able to recommend patients who would benefit from a care plan.

- Comprehensive Assessment: A thorough evaluation of the patient’s medical history, current health status, psychiatric conditions and social needs is conducted by the multidisciplinary team. This assessment helps to identify the factors contributing to frequent ED use.

- Goal Setting: The patient is involved in setting realistic and achievable health goals. This might include improving management of chronic conditions, securing stable housing or reducing substance use.

- Care Plan Development: The multidisciplinary team develops a detailed plan that outlines specific interventions across different healthcare settings. This includes coordinating primary care visits, connecting the patient with social services and providing ongoing psychiatric support.

- Implementation and Monitoring: Once the care plan is in place, it is essential to monitor the patient’s progress. Real-time alerts and communication between providers allow for timely adjustments to the plan as the patient’s condition evolves.

- Ongoing Adjustments: As the patient progresses, the LCP should be regularly updated to reflect any changes in the patient’s health or social circumstances. The care team remains in constant communication to ensure the plan remains effective.

Implementation and Management

Successful implementation of an LCP requires seamless communication between healthcare providers and the use of technology to track SHU visits in real-time. ED triage systems can flag SHU patients, ensuring that their LCP is activated and apparent at the initiation of the ED visit. This approach allows healthcare teams to follow established protocols, ensuring the patient receives consistent care. Over time, the coordinated care outlined in the LCP reduces the need for repeated ED visits, as patients receive more appropriate care in outpatient settings.

Case Study: SHU Program at NYP/WCM

At NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medicine, a program was developed to implement LCPs for 15 super-high utilizers5. The outcomes were remarkable: ED visits were reduced by 70%, hospital admissions decreased by 74%, and the healthcare system realized significant cost savings. Over a 2.5-year period, the program prevented 575 ED visits and 167 hospital admissions, resulting in a savings of $862,500 from reduced ED visits and $2.5 million from fewer hospital admissions5. This case study illustrates the potential of LCPs to significantly improve patient outcomes and reduce healthcare costs when applied effectively.

Challenges in Implementation

Despite the clear benefits of LCPs, several challenges remain in their widespread implementation. EHR interoperability is a major barrier, as inconsistent electronic health record systems between healthcare providers hinder the sharing of care plans. Patient noncompliance is another significant obstacle, particularly among SHUs who struggle with factors like homelessness, substance use or mental health disorders. Additionally, resource limitations within emergency departments, such as a lack of staffing or time to create individualized care plans, can make it difficult to sustain LCPs in the long term.

Conclusion

Longitudinal care plans are a highly effective strategy for managing super-high utilizers in the emergency department. By coordinating care across healthcare settings, LCPs reduce unnecessary ED visits, improve chronic disease management and lead to better outcomes for both patients and healthcare systems. However, addressing challenges such as EHR interoperability, patient compliance and resource allocation is critical for maximizing the potential of LCPs in emergency medicine.

References

-

- Lantz PM. “Super-Utilizer” Interventions: What They Reveal About Evaluation Research, Wishful Thinking, and Health Equity. Milbank Q. 2020 Mar;98(1):31-34. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12449. Epub 2020 Feb 7. PMID: 32030820; PMCID: PMC7077764.

- Dykes PC, Samal L, Donahue M, Greenberg JO, Hurley AC, Hasan O, O’Malley TA, Venkatesh AK, Volk LA, Bates DW. A patient-centered longitudinal care plan: vision versus reality. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014 Nov-Dec;21(6):1082-90. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-002454. Epub 2014 Jul 4. PMID: 24996874; PMCID: PMC4215040.

- Rinehart DJ, Oronce C, Durfee MJ, Ranby KW, Batal HA, Hanratty R, Vogel J, Johnson TL. Identifying Subgroups of Adult Superutilizers in an Urban Safety-Net System Using Latent Class Analysis: Implications for Clinical Practice. Med Care. 2018 Jan;56(1). doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000628. PMID: 27632768; PMCID: PMC5406260.

- MacEwan SR, Chiang C, O’Brien SH, Creary S, Lin CJ, Hyer JM, Cronin RM. Comparing super-utilizers and lower-utilizers among commercial- and Medicare-insured adults with sickle cell disease. Blood Adv. 2024 Jan 9;8(1):224-233. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2023010813. PMID: 37991988; PMCID: PMC10805643.

- Shemesh AJ, Golden DL, Kim AY, Rolon Y, Kelly L, Herman S, Weathers TN, Wright D, McGarvey T, Zhang Y, Steel PAD. Super-High-Utilizer Patients in an Urban Academic Emergency Department: Characteristics, Early Identification, and Impact of Strategic Care Management Interventions. Health Soc Work. 2022 Jan 31;47(1):68-71. doi: 10.1093/hsw/hlab041. PMID: 34910122; PMCID: PMC9989726.

2024 New York ACEP Unsung Heroes of Emergency Medicine

Thank You, Emergency Medicine Heroes. A New York State Emergency Medicine Unsung Hero goes beyond simply being the embodiment of what it means to be an emergency physician. They are a stalwart of the emergency department, who is deeply committed to the mission of the emergency department, their colleagues, co-worker and patients. The unsung hero is always willing to help a colleague – within the clinical environment or not. They are the trusted individual who is known to bring comfort and a smile to the faces of all those around.

Emergency Medicine Resident Committee

Carlton C. Watson, MD MS

Chair, Emergency Medicine Resident Committee

PGY-3

Vassar Brothers Medical Center

Breaking Bad..News

Breaking bad news is one of our most difficult tasks as emergency medicine physicians. In the fast-paced, high-pressure emergency department (ED) environment, we often deal with patients and families during their most vulnerable moments. Delivering the news that a loved one has died, that a diagnosis is terminal or that the prognosis is grim, requires not only clinical skill but also deep emotional sensitivity. It’s a moment that transcends the technicalities of medicine—a human interaction that often remains a forever memory in those involved. These are moments when we stop being just doctors and become the bearers of someone’s worst fears. How do you deliver bad news? Do you have a standardized approach or does it change based on the situation?

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s model of the five stages of grief—denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance—remains a useful framework in these moments. When delivering devastating news, families may immediately enter denial, unable to process the shock of what they’ve just heard. As physicians, we may also encounter anger, often misdirected at us or the medical system, as the recipients grapple with the unfairness of their loss. It’s crucial to recognize these responses as part of a natural process. Understanding these stages allows us to meet the grieving family where they are emotional, offering compassion without feeling the need to “fix” their emotions.

In my own experience, the moments I’ve spent sitting in silence with a family after breaking bad news have been some of the most profound of my career. I’ve learned that sometimes, there are no perfect words—no phrases that can truly ease their pain. What they need, more than anything, is presence. Sometimes, it’s the small gestures—a gentle touch on the shoulder, an acknowledgment of their pain—that resonate the most. I remember once sitting with two young adult brothers who had just lost a father. I also remember delivering the unfortunate news to a mother that despite all of our efforts, her daughter, who was a mother herself, was dead. There was no script to follow, just raw emotion in the room. Those moments, though heart-wrenching, were a reminder that being human in those times is more important than being a doctor with answers.

Despite the emotional toll it takes on us as physicians, breaking bad news is a sacred responsibility. We are the bridge between life as it was and life as it will be after the news sinks in. While the ED can feel like a revolving door of crises, the few minutes we take to deliver this news with care, dignity and empathy can make all the difference in how a family remembers this moment for the rest of their lives.

Yet, we must also remember to care for ourselves. The emotional weight of these encounters can be heavy, and it’s easy to carry the grief of our patients and their families with us long after our shift ends. Seeking support from colleagues, mentors or even mental health professionals is not a sign of weakness but of wisdom. After all, the ability to offer empathy and comfort is something that, if we’re not careful, can drain us if we don’t nurture our own well-being. In learning to support our patients through grief, we must also learn to process and release the grief we inevitably carry.

Social Emergency Medicine

The MATTERS Team

Interviewees:

Joshua Lynch, DO FACEP

Associate Professor of Emergency & Addiction Medicine

University at Buffalo & Chief Medical Officer, MATTERS

Lucy Connery, MPH

Marketing Coordinator, MATTERS

Interviewers:

Joshua Schiller, MD

Director of Global Health/Social Emergency Medicine

Attending Physician

Maimonides Medical Center

Sophia Lin, MD FPD-AEMUS

Assistant Professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine and Clinical Pediatrics

Director of Emergency Ultrasound

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medicine

Can you tell us about the MATTERS program, and how it is relevant to EM practice?

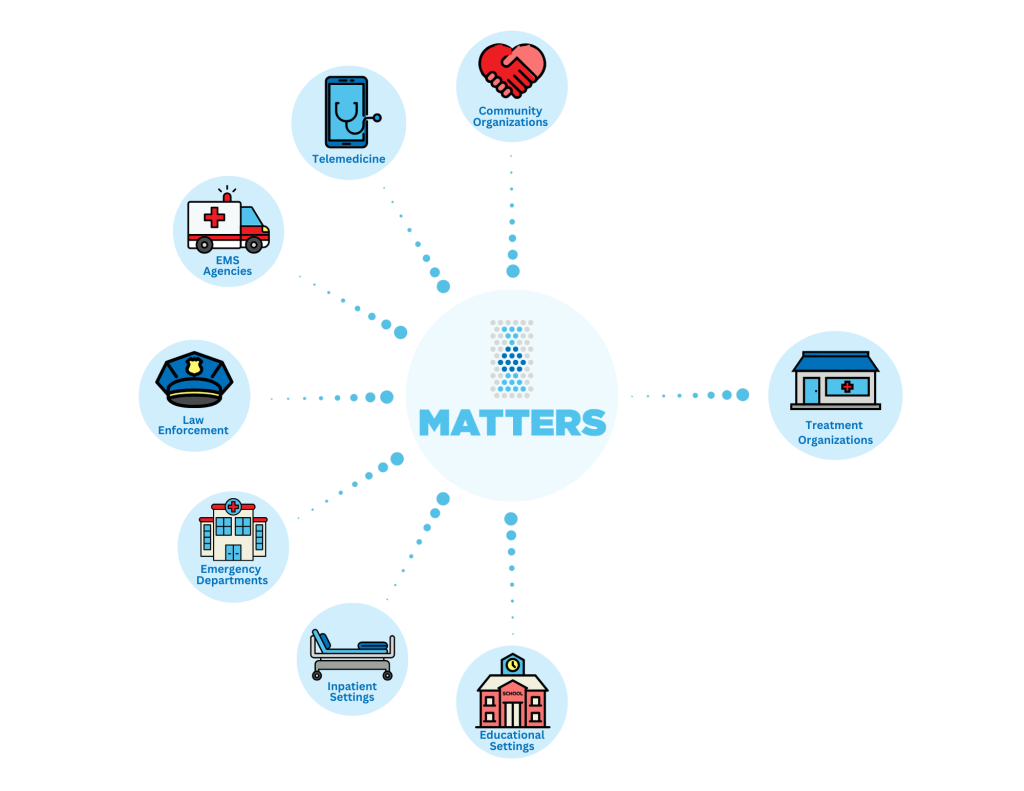

MATTERS was developed to serve as a “one-stop” solution to linking people with opioid use disorder (OUD) out of the emergency department. We efficiently connect individuals with OUD to an outpatient treatment organization of their choice through our rapid referral platform. Patients choose from over 2,500 weekly appointment slots that are offered by over 250 unique treatment organizations and can choose to follow up in-person, virtually, or in a hybrid model. Individuals are also provided with several barrier-reducing resources and services at their time of referral to ease the minds of emergency medicine (EM) providers when sending patients for follow-up treatment. EM providers can submit referrals in as little as three minutes, and we’ve ensured that the process is efficient and intuitive so that it doesn’t impose any unnecessary burden on their existing workflows. This program is especially relevant to EM practice as emergency departments (ED) are typically the ‘first line of defense’ for individuals with OUD who present in acute withdrawal/post-overdose. If this process can work in large tertiary care centers along with small critical access hospitals, it can work almost anywhere.

How is MATTERS able to provide for your patient communities?

We’ve expanded our platform and services through a patient-centered approach by listening to feedback from patients and network partners. Patients choose where they want to follow up based on their geographic location, preferred treatment model (virtual, in-person, hybrid), and other services offered by each participating treatment organization. These treatment centers will accept any patient regardless of insurance status, polysubstance use, and previous treatment history. As part of the referral process, the MATTERS medication voucher is automatically issued to uninsured and underinsured individuals to cover the cost of up to 14 days of any combination buprenorphine/naloxone prescription that is issued at the time of referral – and we recommend this “bridge prescription” in our standardized protocol to ensure patients have flexibility when they’re following up to care. MATTERS also automatically provides a free, round-trip ride to patients who need it for their first follow-up appointment, no questions asked. Everyone referred through our program can opt-in to be contacted by a peer in recovery, offering an extra layer of support during the earlier stages of their recovery. Our staff also follows up with everyone within 72 hours of their referral to help navigate barriers to treatment and link patients to the support services they need to succeed. We then follow up again at 30, 60, and 90 days to ensure continuity of care.

ALL OF THIS is completed in as little as three minutes. Individuals who are not linked to care can visit our website and get evaluated for substance use disorder through our telemedicine services. In as little as an hour, people are connected via video with a prescriber, where they can receive a prescription for medications for OUD (MOUD) and receive a MATTERS referral with all of the wrap-around services we offer. This reduces barriers to treatment for many people with significant transportation barriers.

We also understand that not all patients are ready for treatment. For people who are unsure about seeking treatment, we distribute free harm reduction supplies to anyone across our networks. This not only helps prevent the risk of overdose, but also creates a relationship with people who use drugs so that if/when they are ready for treatment, they know we are here to help.

Are there certain demographics that are particularly affected by this programming?

For the first time in nearly a decade, national rates of opioid overdose deaths decreased in the U.S.; however, this is mainly applicable to Non-Hispanic White populations. Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities are affected by opioid and substance use disorders at a disproportionately higher rate compared to their white counterparts. We also know that people experiencing homelessness are disproportionately affected by substance use disorder due to the unique challenges they face. This calls for services to provide barrier-reducing support to engage marginalized communities.

We also know that there are inequities in the kinds of MOUD these communities receive. Unfortunately, Black and Brown communities are much less likely to be prescribed buprenorphine when compared to White individuals. There are various reasons for this, but the leading “cause” is racial bias and systemic discrimination. We focus on expanding access to buprenorphine across all communities through standardizing prescribing protocols for physicians new to providing MOUD treatment.

How did the development of MATTERS come about?

After years of working in the emergency department, there was a common theme: people with OUD were repeatedly coming back to the ED for treatment. We thought to ourselves: what isn’t working? When we asked the patients this question, we often heard that they were discharged with a long list of phone numbers to call and schedule a follow-up appointment for treatment. When patients tried to call these numbers, they were either out of service or an appointment wasn’t available for weeks at a time. This led to patients feeling like they were at yet another dead-end when seeking treatment and resulted in them returning to the ED.

The fact of the matter is that the experience would be much different if the patient presented with a cardiac concern. Those patients are immediately prescribed medication and receive a follow-up appointment before they leave the hospital. When we asked treatment organizations, they were eager to accept new patients. They needed some scheduling flexibility, but they were not as overwhelmed as we initially thought.

That is when the MATTERS concept was born: we wanted to streamline the process of linking people with OUD to outpatient treatment. In partnership with UBMD Emergency Medicine—the physician group affiliated with the University of Buffalo— we onboarded one major hospital and three community-based treatment organizations as a pilot to demonstrate proof of concept. Each treatment organization chipped in weekly appointment availability so one single organization would not be overwhelmed. We have put the patient first and allowed them to choose which location they wanted to follow up at, which helped build autonomy and empowerment in their recovery journey.

How important is collaboration with other healthcare institutions locally for the treatment of addiction? What specific institutions have you found instrumental in treatment?

Collaboration has been vital for our program’s success. We know that our healthcare system is siloed, and instead of re-creating the wheel, we wanted to connect pre-existing resources to provide the best receiving network for patients. Local organizations are already committed to improving access to treatment for OUD because many of them know how pressing the issue is within their communities. Partnering with local organizations is also key because most patients want to receive treatment and support from someone familiar, not someone from across the state.

Without the support from the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biological Sciences at the University of Buffalo, as well as UBMD Emergency Medicine, our program would not be possible. Key stakeholders in expanding treatment include hospitals, insurance companies, law enforcement, EMS agencies, telemedicine agencies, EMS professionals, and peer organizations. Statewide institutions, such as the New York State Office of Addiction Services and Supports and the NYS AIDS Institute, have been instrumental in expanding the MATTERS program.

How is MATTERS presented/taught to other staff in your department?

MATTERS focuses on reframing how we think about addiction. We define OUD as a severe, life-threatening disease that typically requires treatment with medication. We try to use the term “medication for addiction treatment” rather than “medication-assisted treatment.” Why? Because for OUD, the medication is the treatment. It does the heavy lifting rather than assist in treating the condition.

When we present on the MATTERS program, we also focus on reducing the stigma associated with OUD. In medicine, we still refer to this disease as “abuse,” which can be stigmatizing and “othering” to patients. Abuse is such a negative, powerful word that carries a negative connotation. We draw attention to the fact that no one would choose to experience OUD, and OUD does not discriminate. When we address common barriers to treatment or meet a patient’s basic needs, they are much more likely to follow up for treatment. We also like to frame MATTERS as a one-stop solution for patients and providers alike. We built this program to be simple and effective for busy EM physicians trying to link patients to treatment.

What are common challenges encountered with MATTERS? How are they overcome?

Even with all of the support services we offer, it is difficult to consistently reach marginalized communities, specifically homeless populations—without a phone, email, or consistent transportation; it can be difficult to stay linked to care for this demographic. Another challenge is funding. Initially, we received several pilot grants to build MATTERS (from the Blue Cross Blue Fund along with the Oishei Foundation in Buffalo, NY). More recently as the program has grown, we have partnered with several New York State Agencies (primarily NYS Department of Health and OASAS) for support of the MATTERS program. We are evaluating options for federal funding to assist in the ability to offer MATTERS services to additional states.

We have overcome these challenges by improving access to our services. In the summer of 2022, we launched the MATTERS Network mobile app to place our resources directly at the fingertips of folks who need them most. We’ve also expanded to offer follow-up support services so that if someone is having a hard time staying linked to care, we can address those issues on an individual basis.

What advice can you offer to EM physicians interested in initiating a similar program to MATTERS but who have no background or training in this field? What are the first steps they can take to pursue this interest?

The first step is assessing the resources already available in your region. Recreating the wheel will always take longer and will be more complicated than building strategic partnerships with community-based organizations working toward the same goal as you. Use MATTERS as a resource! We’ve built this program with deliberate attention paid to the ability to replicate across the country in any emergency department (and beyond). We strive to serve as a national model for linkage to treatment for complex disease processes including, but not limited to, OUD, hepatitis, HIV, and mental health.

We’ve done a lot to build this program, and we want it to serve as a model for innovative treatment for OUD. Review our published research articles where we outline the development and results of the MATTERS program and other similar initiatives to better understand how you may start a similar program.

Education

Sophia Lin, MD FPD-AEMUS

Assistant Professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine and Clinical Pediatrics

Director of Emergency Ultrasound

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medicine

Jonathan St. George, MD

Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medicine

The New Learning Space: Can Design Thinking Transform How We Learn?

The Learning Challenge

It’s no exaggeration to say that how we learn in healthcare can be demoralizing. Imagine another intense day of clinical care. The miles on the commute home feel longer than usual. You sink into the couch and use that last ounce of decision-making ability to settle on leftovers for dinner.

That is, until you check your email and realize you have several overdue compliance requirements. Now online, you click from one video to the next, reviewing low-yield content that requires just enough of your attention so you can answer the final quiz and get your credit for CME.

This scene plays out daily in clinicians’ lives at a time when how we learn has never been more critical. In a healthcare system undergoing rapid transformation and disruptive change, learning often becomes another checkbox requirement rather than what it could be – an antidote to complexity and burnout.

Our work in MedEd innovation shows that focusing on how we learn, not just what we learn, can be an effective way to address this problem. By creating better methods of delivering knowledge and skills, we can help clinicians be more adaptable and resilient and assist them in navigating complexity. We can address burnout by using education design to reconnect us with the heart of our profession. Great learning reminds us that what we do matters, connects us with our colleagues and patients, and inspires us to continue the journey of lifelong improvement.

Medical educators can lead this transformation by becoming design thinkers and innovators. They can create the next generation of learning systems that “meet us where we live,” integrate seamlessly into our workflow, merge digital and physical space to enhance our learning environment and make education more collaborative and engaging.

If what we learn is the fuel that powers our clinical judgment, how we deliver that learning is the pipeline through which that fuel flows. How well we build that pipeline will determine how effectively new ideas, knowledge, skills and technology flow to the bedside. This has consequences for both patient care and the well-being of the caregivers providing that care.

Our Work

Our education team at Weill Cornell Medicine took a collaborative design thinking approach to teaching high-quality airway management skills relevant to learners at all levels of experience, from medical students to experienced clinicians. We connected experts and physician educators with a diverse group of creative partners and deliberately searched for inspiration from outside traditional medical education sources to produce an innovative learning format to teach complex concepts and procedure skills in airway management. The result of these efforts is the Protected Airway Collaborative.

We first evaluated the strengths and weaknesses of current airway training methodologies and identified a core set of “built for humans” design principles. These principles focused on the learner and guided the development of our new learning delivery system.

Design Principles

- Focuses on how we learn

- Addresses human factors

- Applies adult learning theory

- Meets learners where they live

- Integrates seamlessly into the workflow

- Works for the environment in which it’s deployed

- Uses readily available “off the shelf” technology

- Merges digital and physical space

- Serves as a sandbox for further innovation

- Encourages collaboration

- Promotes diversity

- Seeks to inspire

The core team expanded its collaboration beyond the academic medical community by inviting artists, content creators, fabricators, graphic designers, storytellers and engineers to participate individually and through partnerships with educational institutions including the School of Visual Arts and Cornell Tech. This purposeful inclusion from outside the medical community provided skill sets currently unavailable within medical education and offered solutions arising from a diversity of perspectives.

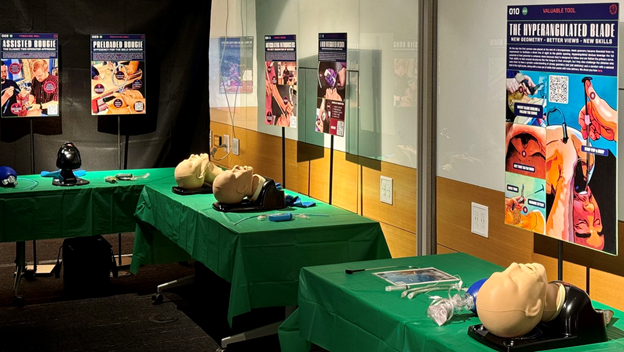

Exhibits at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) served as our original design inspiration. MoMA’s exhibits create an immersive, interactive, self-directed learning experience through art, space, light, guided audio, graphic design and multimedia tools. This highly successful educational format engages millions of people every year with varied levels of subject matter expertise. We chose to model our educational framework after MoMA’s exhibits because of the numerous potential benefits of a more immersive and integrated teaching style.

Our design challenge was to leverage digital and physical space to recreate a museum-style experience in a low-cost and easily reproducible format using off-the-shelf technology.

The Digital Space

We evaluated multiple digital platforms for their ability to function as part of an immersive physical learning space. We developed an ecosystem of free digital tools, including Twitter, YouTube, Instagram and SoundCloud, to create a library of original content and a network of curated online resources. A low-cost website using WordPress (a user-friendly platform that allows medical educators with no web design experience) was used to organize this digital content into a theme-based curriculum similar to a series of online courses.

This online ecosystem stands independently as a valuable collection of educational resources. However, the intention was never to add to the crowded world of online courses or the growing number of social media “influencers” in medicine but to use these tools in a new way: through the seamless integration of digital content that is adapted to function in an immersive and interactive physical learning environment.

Our goal was to design education that operates both digitally and physically, enhancing the benefits of each.

The Bridge

The next challenge was creating a low-cost and reliable method of delivering this adapted digital content to learners in a physical space. We solved this digital/physical divide by applying graphic design principles to create a unique poster format as the basis for our immersive, interactive and exploratory museum-style experience.

Graphic design, as defined by the American Institute of Graphic Arts (AIGA), is “the art and practice of planning and projecting ideas and experiences with visual and textual content.” A ubiquitous feature of our daily lives, it is an overlooked and underutilized resource in medical education.

A well-designed poster is a workhorse of information delivery that captures attention, shares ideas and disseminates information. Until now, its use in medical education has been relegated to scientific poster presentations.

The interactive infographic posters prototyped for this project utilize the power of graphic design in several innovative ways: to deliver information, transform physical spaces and connect with multimedia content.

Each poster created for this project independently delivers important narratives, concepts, clinical pearls, memes, cognitive tools, practice-changing evidence or steps of clinical procedures. High-impact text and graphics are used to capture the eye, engage learners and draw them into the learning experience we developed.

Posters are grouped together in series. Each poster is an integral component of a layered theme-based narrative containing multiple voices and perspectives. In each series, various learning styles are incorporated to cover all the concepts and skills required to master a particular topic.

We applied graphic design principles to both transmit information in an engaging visual format and develop a “visual language” for the posters. This visual language provided a functional element to our immersive, interactive, museum-style learning space. Each poster in a thematic series uses color, a three-letter code and a numerical sequence that allows a series of posters to guide learners through the physical space created.

This graphic design-based schema originates from Massimo Vignelli’s iconic graphic design for the New York City transit system in the 1960s. Using color, circles, numbers and letters, his subway map transformed how people navigated the city’s subway system. Similarly, the poster prototype’s visual language guides learners through the physical learning space while still allowing them the freedom to travel within that space in any way that suits their learning objectives.

We embedded QR codes to connect learners with digital content. Upon snapping a QR code with their mobile device, learners see a digital copy of the poster, allowing them to feel and understand the connection between digital and physical space. An audio introduction recreates the museum tour experience and learners can then access all related multimedia content by scrolling down the web page.

These interactive infographic posters connect learners with relevant digital content within a physical space, allowing both to become more than the sum of their parts and creating the backbone of a learning experience that moves seamlessly between these previously divided domains.

The Physical Space

We grouped posters in theme-based series and utilized elements of simple pop-up exhibitions in defining our physical space, thereby solving a critical aspect of our design challenge. Our team focused on building an immersive, interactive, self-guided learning experience within this newly defined physical space. We focused on providing the hands-on training required to teach complex airway procedural skills in a format that existing digital content and online courses cannot deliver.

This required thinking about digital content creation with the physical environment in mind: integrating the digital content with laryngoscopes, airway trainers, fabricated models and other equipment to facilitate immersion into a sensory experience in which the digital space and physical space are complementary.

The Experience

These new learning spaces were designed to be self-directed, immersive and interactive. The theme-based interactive infographic posters are transportable and can thus transform any existing room into a museum-style experience.

Opportunities to develop core knowledge and skills occur in these spaces in a judgment-free zone. This allows learners to customize their learning, problem-solve and practice skills before receiving feedback. It encourages them to return to the self-directed portions of these spaces with more focused and refined learning objectives. The ability to rapidly cycle back and forth from coaches to self-directed portions of a learning space until mastery is achieved is a crucial design feature of the overall learning experience based on Kolb’s learning cycle.

A guide and point system gamifies the experience and functions as an assessment tool. After obtaining enough points, learners earn credit for completing the space. The assessment tool also allows the design team to see where learners are struggling and use this feedback for iterative improvements.

The Benefits

Traditionally, only online courses can run asynchronously. However, a major limitation of online courses is they cannot accommodate hands-on practice for procedure skills. Pop-up educational courses combining digital and physical content are different and can provide both asynchronous learning and hands-on experience. These courses are not limited by the time constraints of traditional courses and can be set up for days, weeks or even months to allow large numbers of learners to engage with the content and practice essential skills in pop-up spaces. The portability of the digital content and posters allows tremendous flexibility in the physical spaces that can be used. These spaces can include resident rooms, empty conference rooms or other common hospital spaces.

Our new learning model’s open-source and collaborative design complements other teaching approaches, including simulation. The flipped classroom element of our educational experience makes it ideal for integrating simulation as a capstone experience. Simulation cases are used to solidify the bridge between the digital and physical spaces by incorporating learning objectives drawn from the learning spaces themselves.

Another feature of this new learning model is the inclusion of diverse perspectives and even participants’ voices within the larger theme-based narrative. Participants are invited to record de-identified stories about challenging airways on video or in writing. Stories are then shared via the course’s website and the poster QR codes at relevant stations. Storytelling helps participants reflect upon difficult learning experiences. Interacting with others’ stories helps normalize anxiety around difficult airways so that the learners can focus on skill-building both during and after the course.

Our course design frees faculty from teaching in a one-size-fits-all format. The flipped classroom model enables learners to build confidence first before needing to demonstrate technique. As a result, an educator can work one-on-one with learners and tailor what they teach to a specific learner’s needs and skill level, making the process more enjoyable and efficient for both the educator and the learner.

Since the course’s backbone is a website designed to integrate digital and physical space, it is also infinitely scalable, allowing unlimited online and in-person learning. Through the printed posters, the website can run an endless number of our pop-up learning spaces across the globe without concern for geographic location or time. Remote coaching expands the potential of these new learning spaces, increasing the number of available educators and making the workflow for educators and learners more efficient. The course design also allows consistency to be built into the system. Providing a framework of instructional tools and materials means that many learners can be taught without significant variation or erosion in the quality of learning as the system grows.

We are particularly interested in evaluating this model as a low-cost teaching tool for healthcare systems in resource-limited communities. As most of the work is done on the front end with creation of digital content and posters for a physical pop-up space, the cost for others to implement the course is relatively low.

The collaborative and open framework of this course is fertile ground for further innovation. It provides a platform for studying and testing tools such as AI XR and attracts collaborations with fabricators, such as the Maker Lab at Cornell Tech, to design low-cost models that integrate into physical spaces. It also draws interest from illustrators, artists and content creators to develop engaging audio, video and graphic design features.

Next Steps

We have used this system to teach thousands of learners across our institution, the country, and internationally by deploying posters and equipment in break rooms, resident rooms, classrooms and other pop-up locations. From its inception as a small local project, it has morphed into a nationally and internationally recognized airway course.

A transformation in healthcare delivery can occur only if there is a similar transformation in learning delivery. We hope that our collaborative, low-cost approach, using available technology and existing resources, sparks further interest in medical education innovation, provides a roadmap for overcoming some of the barriers to learning in today’s healthcare environment and creates opportunities to develop new pathways toward viable solutions that inspire and teach physicians for generations to come.

Resources

The Protected Airway Collaborative

https://theprotectedairway.com/

Design Thinking

https://readings.design/PDF/Tim%20Brown,%20Design%20Thinking.pdf

Sandars J, Goh PS (2020). Design Thinking in Medical Education: The Key Features and Practical Application. J Med Educ Curric Dev. Published 2020 Jun 4.

Madson, M. J. (2021). Making sense of design thinking: A primer for medical teachers. Medical Teacher, 43(10), 1115–1121.

Graphic Design

https://icenet.blog/2020/09/22/presentation-design-for-medical-educators/

Membership Engagement and Development

Interviewer

Moshe Weizberg, MD FACEP

Medical Director, Emergency Department

Maimonides Midwood Community Hospital

Chair, New York ACEP Professional Development Committee

Interviewee

Jessica L. Smith, MD FACEP

Director of Graduate Medical Education

Designated Institution Official

Associate Chief Medical Officer

Brown University Health

Professor, Clinical Educator in the Department of Emergency Medicine

The Alpert School of Brown University

I had the opportunity to interview Dr. Jessica L Smith, MD, FACEP. Dr. Smith is the Director of Graduate Medical Education (GME), the Designated Institutional Official (DIO) and the Associate Chief Medical Officer (ACMO) at Brown University Health in Rhode Island. She is a Professor, Clinician Educator in the Department of Emergency Medicine at The Alpert School of Brown University. We spoke about her DIO role and how to develop a career in education and leadership to attain that position.

INT: What is the day-to-day job of a DIO like?

JS: Just like in emergency medicine, the day-to-day life is about putting out fires. As a DIO, I kind of consider myself the Program Director of all the Programs, but with a lot more responsibility across the institution. I have the opportunity to help manage outside my own specialty of emergency medicine, which includes everything from helping Program Directors manage their Programs, empowering Program Coordinators be part of the administrative leadership dyad with their Program Directors, as well as helping the residents and fellows have great clinical and educational experiences in their training Programs, all while functioning in an increasingly complex healthcare system. Because of my position as DIO and Director of GME and through my reporting lines to the C-suite, that also puts me at the table as an executive within the hospital leadership. So I also work closely with Departments and Department Chairs regarding their personnel, because when faculty are interacting with residents and fellows at any level, there can sometimes be friction that arises and I can help manage that. On the flip side, there is also a number of opportunities for education and research projects, and the GME office can help keep all parties engaged and aware of those resources.

INT: So, it sounds like you are often trying to “bridge the gap” between different Departments and their respective needs. I can assume that would be challenging at times.

JS: It is very challenging at times because there is sometimes tension between what Departments want and need from an operations standpoint and what Program Directors want and need from an education and training standpoint. It is the perennial balance between service and education as trainees work and learn at the same time. As we all know, it is tricky and sometimes there are competing interests between those two entities and the balance tips in one director or the other.

INT: Do you have any tricks on how you navigate that?