It’s likely every emergency medicine (EM) physician’s worst nightmare (or at least one of the many): An imminent or precipitous delivery. Two patients for the price of one and so much can go wrong. But as is an ever-running theme in our specialty, we must be prepared for anyand everything that comes through our doors.

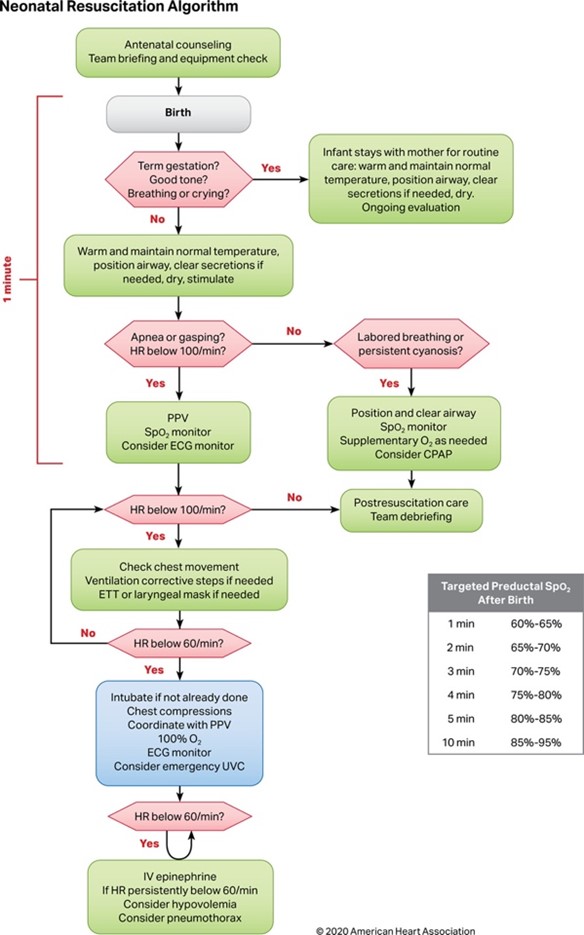

The good news is if this does occur on shift, the likelihood you will need to do much more for this new addition to the world apart from a quick neonatal evaluation and cord clamping is low. Studies suggest only about 10% of all newly born infants require some breathing assistance at birth, with extensive resuscitation necessary in up to 1%. Even with this relative rarity, neonatal mortality in the US is about 4 per 1000 live births and many EM physicians feel they need more exposure to neonatal resuscitation. So, without further ado, a refresher on the very important topic of neonatal resuscitation. (We’ll leave the Moms for another day).