Case

A 56-year-old female with a significant past medical history of diverticulitis presented to the emergency department with 3 days of worsening left lower quadrant abdominal pain associated with fever, nausea, constipation and decreased appetite. She had been treated for a similar episode of abdominal pain two years earlier and was hospitalized for diverticulitis. Initial vital signs were reassuring with no fever, hypotension or tachycardia. Physical exam revealed abdominal tenderness over the left lower quadrant with localized voluntary guarding. Initial labs were largely unremarkable without leukocytosis. Her presentation was concerning for diverticulitis, however, the differential diagnosis also included other intra-abdominal pathology, including intra-abdominal abscess, colitis, pancreatitis, appendicitis, pyelonephritis and ureteral colic. Computed tomography (CT) abdomen and pelvis with intravenous (IV) and oral contrast was obtained and interpreted as having no acute abdominopelvic findings.

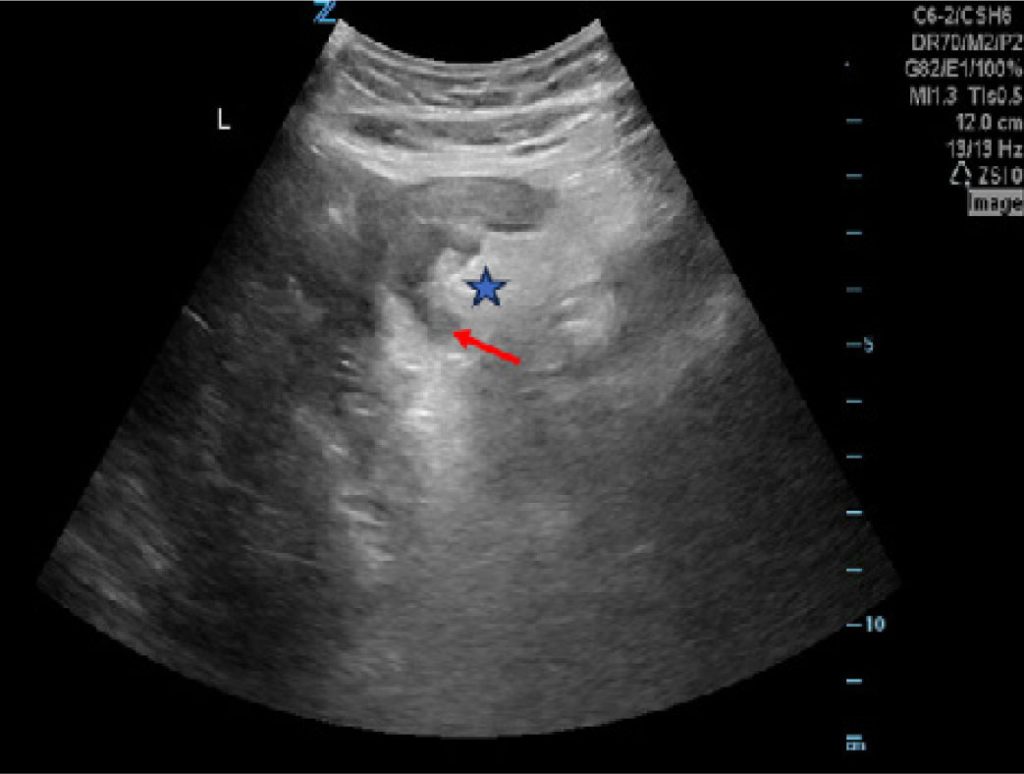

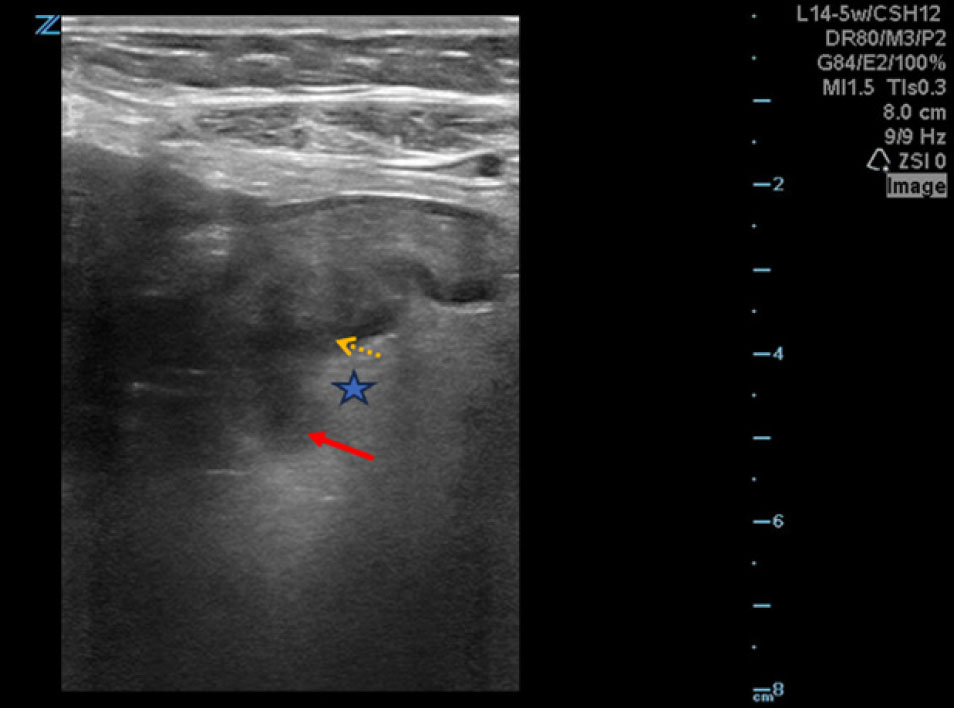

Given the high pretest clinical suspicion for diverticulitis, a bedside point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) was performed using the curvilinear probe (Figure 1) followed by the linear probe to enhance the resolution (Figure 2), which showed hyperechoic pericolonic fat surrounding diverticula, areas of thickened colonic walls and sonographic tenderness of the area consistent with diverticulitis. After further discussion with the radiology attending, the CT interpretation was revised and confirmed our findings suggestive of proximal sigmoid diverticulitis. The patient was admitted to the hospital and was initiated on intravenous antibiotics. Six weeks later, she underwent a sigmoid colectomy for recurrent diverticulitis.