Case

A 77-year-old female with a medical history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia presented to the Emergency Department (ED) after a syncopal episode with pressure-like chest pain radiating to the left arm. She had similar chest pain intermittently for months, but began having palpitations, shortness of breath and lightheadedness the morning of presentation. While walking her dog, she had a syncopal episode and EMS was called. On arrival to the ED, vital signs were normal without hypotension or tachycardia. The EKG demonstrated a LBBB and ST depression in lead II, similar to a prior one from two years ago.

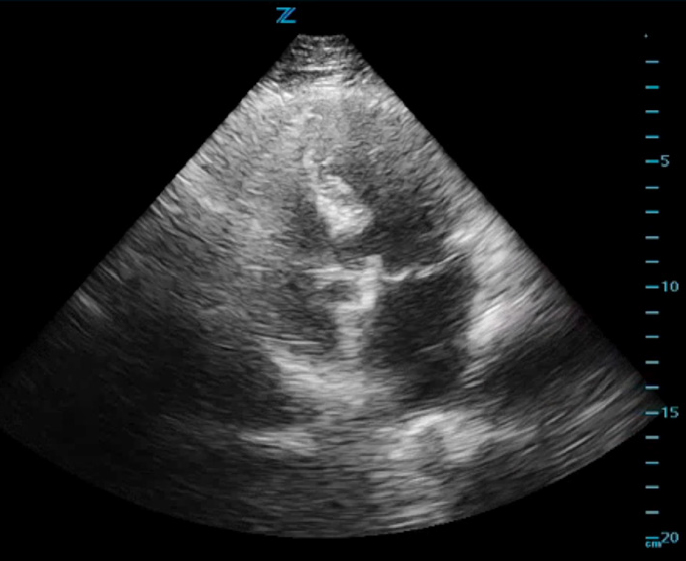

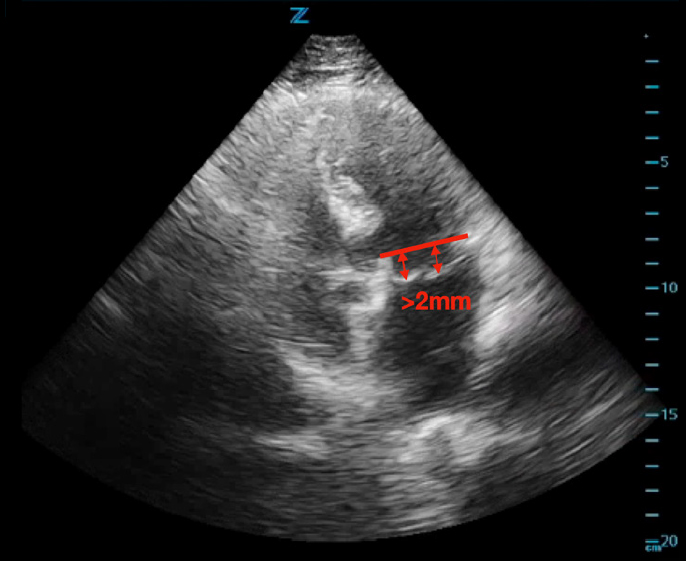

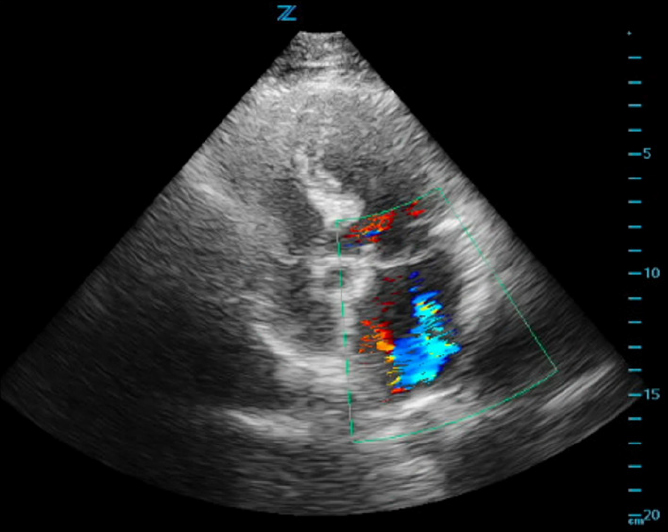

ED cardiac point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) revealed mild left ventricular sigmoid hypertrophy and mitral valve prolapse of both anterior and posterior valves with mitral regurgitation (Figures 1A and 1B). There was normal systolic left ventricular function without segmental wall motion abnormalities or pericardial effusion. There were no anterior or lateral lung B-lines demonstrating pulmonary vascular congestion. The serum troponin level was mildly elevated and remained stable on repeat evaluation.

Consultation with cardiology was initiated due to the ED POCUS findings of mitral valve prolapse and increased suspicion for cardiac dysrhythmia, such as rapid atrial fibrillation, contributing to the patient’s syncope. In conjunction with cardiology recommendations, the patient was initiated on anticoagulation due to suspicion for atrial fibrillation and was admitted to the cardiology service. The patient subsequently underwent cardiac catheterization which showed non-obstructive coronary disease. Inpatient echocardiogram showed a myxomatous mitral valve with moderate prolapse of both leaflets and moderate mitral regurgitation consistent with ED POCUS. She was started on an optimized cardiac medication regimen, including aspirin, atorvastatin and metoprolol. She remained chest pain free and hemodynamically stable during the hospital course and was discharged home with cardiology follow up the next day. This case highlights the crucial role of POCUS in helping to identify the underlying cause of syncope and diagnosing symptomatic mitral valve prolapse.