Jeffrey S. Rabrich, DO MBA FACEP FAEMS

Senior Vice President

Envision Physician Services

New York ACEP is Advocating For You

I hope everyone is staying warm and healthy during the cold winter viral surges. As I write this in mid-January, I am hearing from colleagues around the state about unprecedented boarding. I have learned of several emergency departments holding over 100 patients, with many boarders waiting 48 hours or more for inpatient beds. The challenges we face in the emergency department are greater than previously seen and include not just boarding but short staffing, medication shortages, violence and many unfunded mandates. Even with all the above, when recently reflecting as one often does around New Year, I still would not choose any other specialty. Our impact on patients and their families is greater than any other specialty. So how do we get the public to see our value and help advocate for us? More on that in a little bit.

While by the time you read this it won’t be new anymore, I recently watched the first two episodes of The Pitt which generated strong feelings. We have all seen prior medical dramas, but this one is different. Judging by the comments I have read on social media, as well as discussion with colleagues, this seemed real to us. Many of us had visceral reactions to the Covid flashback (by now I hope this isn’t a spoiler), recognized “those patients”, and even felt anxious wanting to see what the medical student or resident were up to. Basically, we felt seen, and this is a good thing. We live this show every day, know about the boarding and short staffing, the administrator who is laser focused on metrics, and the lack of mental health resources. But we aren’t the audience that needs to be reached, it’s the public, the legislators and the regulators. I watched the show with some non-medical friends who were appalled to learn how realistic the show is. Their take-away: Our job seems impossible.

Why do I mention this show? As we move forward in 2025 it’s all about telling our story in a way that people can understand. We must engender empathy to our challenges and highlight the plight of emergency department patients. So, can The Pitt do for current day emergency medicine what ER did for our specialty in the 90’s? I mean Dr. Carter is a seasoned attending now (alright I know it’s a different character technically but c’mon he’s still Carter). I don’t think we know the answer yet, but I certainly welcome the free attention to the issues and the importance of emergency medicine. So how can we as New York ACEP as well as individuals continue to tell our story to New York and federal legislators and officials? New York ACEP has embarked on several projects to help increase awareness of issues and promote solutions. Just a few months ago we launched an all-new updated website (Thank you Tim and Katelynn!) which makes it easier to find information and allows us to post current items more timely. We have engaged with a communications consultant to help us craft our message to multiple stakeholders, in addition to the legislature, providing multiple platforms for maximum visibility. Additionally, we have our Lobby Day in Albany on March 11, 10am – 4pm. This is an opportunity for us to tell our story and our patients’ stories directly to elected officials. I encourage anyone with interest to join our lobby day. This event is not just for board and committee members, but all of us to advocate for our specialty. We welcome first time attendees, residents and medical students.

Finally, what can you do on your own? Host an emergency department visit for your assembly member, senator, congressman, or other elected representatives. Many of these officials spend time in their district office and are often very willing to come see their local hospital ED (especially if they can combine it with a photo op) and speak with their constituents. These visits can be real life demonstrations of the effects of short staffing, boarding, EMS wait times, and other challenges to EM. Let’s all make one our resolutions this year, to tell our story via all these means to as many people as possible.

Sound Rounds

Thomas M. Kennedy, MD

Assistant Professor of Pediatrics in Emergency Medicine

Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

Department of Emergency Medicine, Division of Emergency Ultrasound

NewYork-Presbyterian Morgan Stanley Children’s Hospital

Di Coneybeare, MD MHPE FAEMUS

Director, Emergency Ultrasound Fellowship

Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine

Department of Emergency Medicine

Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

Alina Mitina, DO

Emergency Ultrasound Fellow

Clinical Instructor of Emergency Medicine

Department of Emergency Medicine

Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

Seeing Beyond the Scope: A Case of Inflammatory Bowel Disease on Point-of-Care Ultrasound

Case

An 18-year-old male with a recent diagnosis of Crohn’s disease (CD) presented to the emergency department (ED) for evaluation of right lower quadrant (RLQ) abdominal pain. The patient reported that the pain began yesterday with a gradual onset in the RLQ and was intermittent. He stated that he vomited four times yesterday with non-bloody and non-bilious vomitus. He reported having a normal bowel movement yesterday, but none today, and mentioned that he has not been passing gas.

Upon arrival to the ED, the patient’s vital signs were as follows: temperature 38.8°C (101.8°F), heart rate 157 bpm, respiratory rate 22 breaths/min, blood pressure 111/56 mmHg, and oxygen saturation 100% on room air. On physical examination, the patient was alert and oriented to person, place and time, well-appearing and in no acute distress. However, he exhibited tenderness with guarding and rebound in the RLQ.

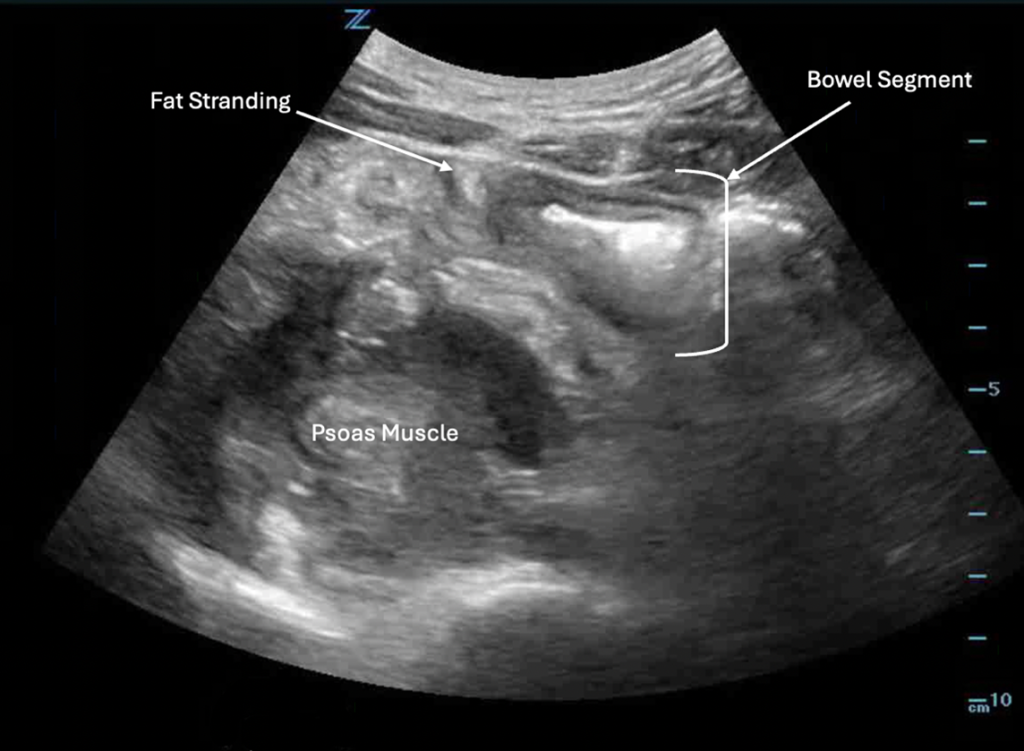

A point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) was performed, revealing a non-compressible segment of bowel in the RLQ near the psoas muscle with surrounding inflamed fat (Figure 1). Although we did not measure the bowel wall thickness (BWT), the ruler on the right side of the image shows that it was >3mm. Additionally, the psoas muscle appeared edematous. The differential diagnosis at that time included appendicitis, small bowel obstruction, and CD flare.

A computed tomography (CT) scan was ordered to further evaluate the ultrasound findings. The CT scan interpretation by the Radiology service stated that findings were consistent with worsening CD and included distal ileal wall thickening, proximal to mid-right colonic wall thickening, mild-to-moderate free fluid predominantly in the right-side of the abdomen and regional fat stranding. Additionally, there was asymmetric prominence and heterogeneity of the right psoas, iliacus, iliopsoas and regional right lateral paraspinal quadratus lumborum musculature, with multifocal areas of contained fluid and air. A borderline fluid-filled appendix was also noted.

The General Surgery service was consulted for definitive management. The patient was treated with antipyretics, intravenous fluids and antibiotics. The surgical service concluded that there was a low suspicion for appendicitis, as the patient’s symptoms were identical to those of his usual CD flares. The inflammatory changes seen on the CT scan were deemed likely sequelae of adjacent inflammation from CD. However, they noted an extensive abscess now involving the right inguinal region. The surgical service recommended transferring the patient to a higher level of care for intervention by a colorectal surgeon, as outpatient management with infliximab had failed.

Discussion

In the United States, an estimated 1.6 million individuals are affected by inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including approximately 785,000 with CD and 910,000 with ulcerative colitis.1 The classic symptoms of CD include abdominal pain, watery diarrhea and weight loss. The abdominal pain is typically colicky in nature and often persists for years before a diagnosis is made. Due to its predilection for the terminal ileum, CD-related pain frequently localizes to the RLQ. This pain can be acute and severe, often mimicking the presentation of appendicitis.1

POCUS is widely used to diagnose appendicitis, with reported sensitivities of 75%–90%, specificities of 86%–95%, and accuracies of 87%–96% in experienced hands.2 Ultrasound diagnosis of IBD and its complications are less widely established. Dolinger et al. propose a standardized protocol for POCUS evaluation of IBD, described below in the Technique section.3 Increased BWT is the most sensitive indicator of disease. Additional sonographic findings consistent with an inflammatory process also aid in the diagnosis of IBD, including:

- Bowel wall hyperemia

- Focal disruption of bowel wall layers (i.e., loss of clear stratification of bowel wall)

- Hyperechoic (bright), thickened mesenteric fat

- Free fluid surrounding bowel

- Mesenteric lymphadenopathy

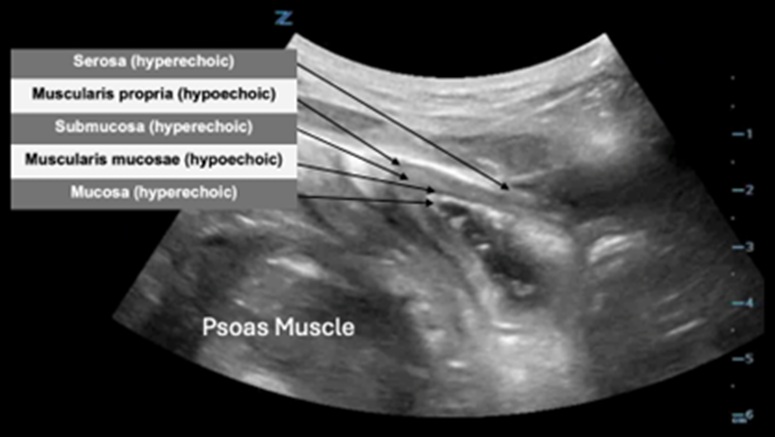

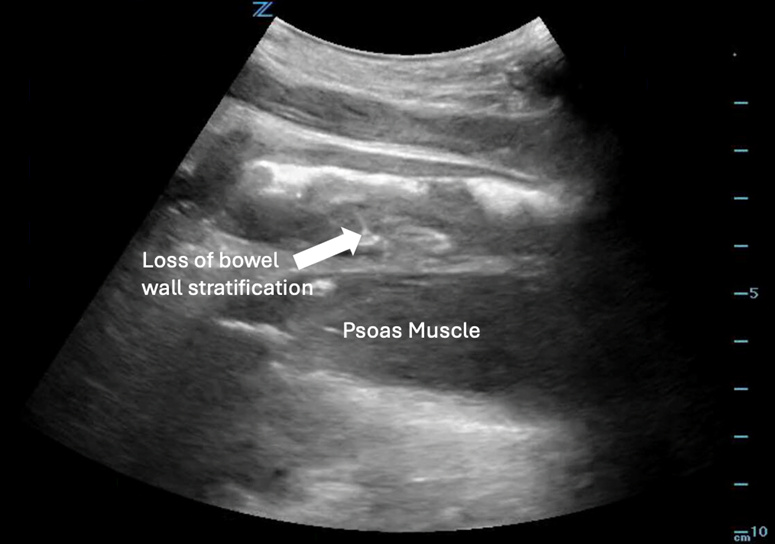

The bowel wall has a characteristic sonographic appearance known as the bowel wall signature. As shown in Figure 2, the bowel wall signature consists of alternating layers of hyperechoic and hypoechoic (dark) tissue. These sonographic layers correspond to the histologic layers of the bowel wall, from inner to outer: the mucosa (hyperechoic), muscularis mucosae (hypoechoic), submucosa (hyperechoic), muscularis propria (hypoechoic) and serosa. Notably, the serosa is often not visible because it is so thin. The BWT is measured from the lumen-mucosal interface to the muscularis-serosal interface.3 POCUS images obtained for our patient demonstrated increased BWT and loss of clear bowel wall layers of the distal ileum (Figure 3), hyperechoic, thickened mesenteric fat and an edematous psoas muscle.

Case Conclusion

POCUS can be used to evaluate and diagnose complications of IBD. Our ultrasound revealed evidence of an inflamed segment of small bowel in the RLQ, identified as the distal ileum on CT scan. Sonographic evidence of inflammation included increased BWT, loss of clearly stratified bowel wall layers and inflammation of adjacent mesenteric fat. Additionally, we identified an abnormally appearing psoas muscle which subsequently was determined to be caused by inflammatory changes from this patient’s CD flare. Considering CD’s predilection for causing RLQ abdominal pain, care must be taken when performing POCUS to differentiate the small bowel from the appendix. This patient was taken to the operating room where he had an ileocolic resection and drainage of a right psoas abscess followed by a successful recovery.

Indications

- Fever

- Bloody diarrhea

- History of IBD

- RLQ abdominal pain

Technique

- A low frequency curvilinear transducer (3-5 MHz) is used to obtain a global view of the bowel. A high frequency linear transducer (5-15 MHz) is then used for more accurate measurement of the BWT.

- Scan sequence:

A) Global assessment:

- Start in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen with a low frequency curvilinear transducer to identify the distal sigmoid colon.

- Anatomic markers: left iliopsoas muscle and left iliac vessels

- Trace the bowel proximally to visualize the following segments:

- Descending colon

- Splenic flexure

- Transverse colon

- Hepatic flexure

- Ascending colon

- Cecum

- Ileocecal valve

- Terminal ileum

B) BWT assessment:

- Use the high frequency linear transducer to measure the BWT of each segment listed above in both long and short axes (measurements in different axes should be taken 1 cm apart and their average used as the BWT of the segment).

- Measurement is taken from the lumen-mucosal interface to the muscularis-serosal interface.

Pitfalls and Limitations

- Failing to correctly differentiate the ileum and appendix, leading to misdiagnosis.

- Though POCUS can be an effective tool to evaluate IBD, no sonographic findings are 100% sensitive or specific for diagnosis of a disease flare.

- There is a paucity of literature investigating the accuracy of POCUS performed by ED healthcare providers to diagnose IBD.

References

- Flynn S, Eisenstein S. Inflammatory bowel disease presentation and diagnosis. Surg Clin North Am. 2019;99(6):1051-1062.

- Cho SU, Oh SK. Accuracy of ultrasound for the diagnosis of acute appendicitis in the emergency department: A systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102(13):e33397.

- Dolinger MT, Kayal M. Intestinal ultrasound as a non-invasive tool to monitor inflammatory bowel disease activity and guide clinical decision making. World J Gastroenterol. 2023; 29(15):2272-2282.

Bernard P. Chang, MD PhD FACEP

Associate Dean of Faculty Health, Columbia University

Vice Chair of Research

Department of Emergency Medicine

Closing the Gap: How Emergency Medicine Can Build a Stronger Academic Future

Emergency Medicine (EM) is a unique specialty—fast-paced, interdisciplinary and built on the principle of being ready for anything at any time. EM physicians thrive on solving complex clinical problems, often in resource-limited settings. Yet, when it comes to scholarly activity, many EM faculty feel ill-equipped and unsupported. A team of Emergency Physicians, led by one of NYACEP’s own (Dr. Nidhi Garg) recently published a “National Needs Assessment of Emergency Medicine Faculty Regarding Scholarly Activity Practices and Support,” in JACEP open, shining a spotlight on this disconnect and offering a roadmap to build a stronger academic foundation for EM. The findings highlight significant challenges faced by EM faculty who want to contribute to research and academic growth. It also provides actionable recommendations for institutions to foster a culture where scholarship can flourish. The study, conducted as a comprehensive national survey, aimed to evaluate the state of scholarly activity among EM faculty, identify barriers to academic success and assess the effectiveness of existing support systems. A total of 1,210 emergency medicine faculty members from academic and community settings across the United States participated, making this one of the most extensive surveys on the topic to date. Respondents were asked to provide detailed feedback on their experiences with scholarly activity, available institutional support, and perceived obstacles.

The results reveal a specialty grappling with systemic challenges but also poised for growth and innovation. Here we’ll dive into some of the study’s high level findings, exploring the broader implications for the field and perhaps raise a call to action for leaders in Emergency Medicine.

Time: The Greatest Barrier

It’s no secret that emergency physicians lead some of the busiest lives in medicine. Between unpredictable shift schedules, clinical demands, teaching responsibilities and administrative duties, it’s a constant race against the clock. The study confirmed what many in the field already know: time—or the lack of it—is the single greatest barrier to scholarly activity.

Over 70% of faculty surveyed cited insufficient protected time as the primary obstacle to engaging in research, writing and academic projects. This challenge isn’t just a matter of poor time management; it’s systemic. Emergency physicians often work irregular hours, leaving little room for the focused effort required to pursue meaningful research.

One survey respondent described the situation succinctly: “We are always in triage mode. It’s hard to focus on long-term goals like research when the immediate demands of patient care are so consuming.”

Inconsistent Support Systems

Beyond time constraints, the study highlighted a significant disparity in the resources available to EM faculty. Faculty at larger academic medical centers reported greater access to research funding, mentorship and infrastructure compared to their colleagues in smaller institutions or community settings. This inequity exacerbates the challenges faced by early-career researchers or those practicing in under-resourced environments.

While many academic centers offer programs designed to support scholarly activity, their implementation and effectiveness vary widely. Some faculty benefit from structured mentorship and dedicated research teams, while others feel they are left to navigate the complexities of academic medicine alone.

The study also revealed a gap in training. Many faculty expressed a need for skill-building opportunities, particularly in research methodologies, grant writing and manuscript preparation. These skills are critical for producing high-quality academic work but are often underemphasized in EM training programs.

Opportunities for Change

Despite these challenges, the study offers hope. Its recommendations provide a clear path forward to support and sustain scholarly activity in Emergency Medicine. Key strategies include:

- Protected Time for Research:

Institutions must recognize that time is the foundation of scholarship. Policies that provide faculty with protected research time—whether through flexible scheduling, grant-funded positions or departmental support—are essential. Protected time isn’t just a perk; it’s a necessity for building a robust academic culture. - Structured Mentorship Programs:

Mentorship plays a critical role in academic success. The study highlights the need for formal mentorship initiatives that pair junior faculty with experienced researchers. These programs can provide guidance, foster collaboration and help early-career physicians navigate the complexities of academic medicine. - Skill Development Workshops:

Regular training sessions on research design, data analysis and grant writing can empower faculty to take their scholarly pursuits to the next level. These workshops should be tailored to the unique needs of EM physicians, taking into account their clinical schedules and professional backgrounds. - Leveraging Technology:

The study also points to the potential for innovative solutions, such as tele-research platforms and collaborative networks. By pooling resources and expertise across institutions, EM faculty can overcome many of the barriers associated with time and resource limitations.

Editorial Reflections: A Personal Call to Action

As an EM physician and academic leader, I’ve seen firsthand the tension between clinical excellence and scholarly ambition in our field. Emergency Medicine is, by nature, a dynamic and ever adapting specialty. Our work is immediate, fast-paced and often unpredictable. But this doesn’t mean we can’t plan for the long term—especially when it comes to research and academic growth.

The challenges identified in this study resonate deeply with my own experiences. Time, as the survey makes abundantly clear, is the most precious resource for faculty. Without it, even the most motivated researchers struggle to sustain meaningful academic work. Departments and institutions must prioritize mechanisms to safeguard research time, whether through departmental grants, adjusted clinical schedules or creative solutions like shared research sabbaticals.

Mentorship is another area where Emergency Medicine can and must do better. A good mentor can be the difference between a promising idea that fizzles out and one that turns into a landmark study. Structured mentorship programs, supported by institutions and professional organizations, should be a cornerstone of our academic culture.

Finally, Emergency Medicine has always been a field that thrives on innovation. We excel at thinking outside the box to solve complex clinical problems—why not apply that same ingenuity to academic medicine? Whether it’s through collaborative research networks, data-sharing initiatives or cutting-edge analytic tools, we have the potential to revolutionize how scholarship is conducted in our specialty.

Building a Legacy of Scholarship

The implications of this study extend far beyond individual faculty members. They challenge us to rethink how we define and support success in Emergency Medicine. By investing in our faculty’s academic potential, we’re not just helping them succeed—we’re advancing the field as a whole.

Research in Emergency Medicine has the power to shape the future of healthcare. From innovations in patient care to systemic improvements in hospital operations, the impact of scholarly activity extends far beyond the walls of the ED. But for this potential to be realized, we need to create an environment where scholarship is not just possible but encouraged and celebrated.

This is a pivotal moment for Emergency Medicine. The challenges are real, but so are the opportunities. Moving forward, we can build a culture of scholarship that empowers faculty, improves patient care and solidifies Emergency Medicine’s place as a leader in academic medicine.

Practice Management

Joseph Basile, MD MBA FACEP

Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine

Medical Director, Clinical Operations

Staten Island University Hospital

Chair, New York ACEP Practice Management Committee

Chris McStay, MD MBA FACEP

Vice Chair of Clinical Operations

Associate Professor of Emergency Medicine

Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons

![ROTTER Ben-Zion_Headshot MD[2]](https://nyacep.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/ROTTER-Ben-Zion_Headshot-MD2-150x150.jpg)

Ben-Zion Rotter, MD

The Dr. Lorna M. Breen EM Healthcare Administration Fellow

Clinical Instructor

Department of Emergency Medicine

NewYork-Presbyterian, Columbia University

Mahesh Polavarapu, MD

Columbia University Medical Center-NYP Hospital

Medical Director, NYP-Westchester Emergency Department

Director, Dr. Lorna M. Breen Emergency Medicine Fellowship in Healthcare Administration

Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine

The Case for Tracking Hallway Use as a Key Performance Indicator

In recent decades, Emergency departments (EDs) have increasingly relied on metrics to track and improve patient care. The Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance was formed in 1994 and, in 2006, held their first summit to standardize operations measures.1 Since then, regulators at the Center for Medicaid and Medicare Services and Joint Commission have adopted several of these measures into their reporting and accreditation frameworks, with an emphasis on throughput metrics.1 CMS mandates the reporting of Left-Without-Being-Seen (LWBS) rates, median time spent in the department for discharged and admitted patients, as well as time-based measures of care related to STEMI, stroke, and sepsis.2

These standardized measures help align department goals and facilitate process improvement. When surveyed, administrators have expressed that time-based metrics help them better understand departmental performance and identify areas for improvement.3 At the same time, increased focus on throughput metrics has pushed departments to move patients out of the waiting room and coincided with a significant rise in hallway use.4,5

One of our community sites has experienced this balancing act firsthand. Over the past few years, we improved our performance on key metrics, including reducing LWBS rates from over 5% to below 2%. However, this success came with a sharp increase in the use of hallway spaces for patient care. Additionally, while throughput measures improved, patient satisfaction scores declined for most domains. This is a pattern echoed across the country.6 Increasingly, critical aspects of patient care—like gathering histories, performing exams and communicating results—are happening in hallways. These makeshift spaces, borne of necessity, are not only unsatisfactory and uncomfortable for patients but can also introduce risks to patient safety.

The harms of ED crowding and hallway use are well documented. Hallway care compromises patient privacy, diminishes care quality, increases violence and moral harm to providers and erodes trust between providers and patients.4,7,8 Studies have linked increased hallway use to increases in diagnostic errors, hospital length of stay, preventable disability, re-admission, and even mortality.5,8–10 Despite these significant risks, hallway use remains a largely unmeasured aspect of ED performance.

The drivers of ED crowding—and the resulting hallway use—are multifactorial. After an initial decline in ED volumes following the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, patient volumes have rebounded, with year-over-year growth largely driven by older patients.11,12 These individuals often require more complex evaluations, longer treatments and are more likely to need inpatient admission.4,5 Additionally, the increasing availability of advanced testing and treatment modalities means that even treat-and-release patients often require longer ED stays before discharge.

Structural changes in healthcare have exacerbated these challenges. National shortages of nurses and support staff, reduced primary care availability and hospital bed reductions have strained EDs across the country.5,13 While many of these issues lie outside the direct control of our specialty, how we utilize our space remains firmly within our scope.

If metrics are to truly reflect the quality of our care, it is imperative that we begin measuring hallway use. This data would provide a more complete understanding of patient flow and care quality, highlighting an issue too easily tolerated. Incorporating hallway use as a key metric would allow us to guide care delivery more thoughtfully and redesign workflows to better balance efficiency with patient dignity and safety.

While hallway use may be unavoidable, it should be minimized and reserved for transitional moments—such as waiting for evaluation or results—not for the delivery of core clinical care. Sensitive conversations, physical exams and the communication of results should occur in private spaces whenever possible. Measuring hallway use could drive process improvements, ensuring that private spaces are prioritized for these critical aspects of patient care.

Beyond guiding internal changes, hallway use metrics could serve as a compelling advocacy tool for systemic reform. There is no standardized measure of ED crowding.4,14,15 Despite years of reporting length of stay for admitted patients, meaningful progress on boarding has been limited. By quantifying the extent of hallway care we can provide administrators with a more vivid picture of ED crowding and its effects on both patient experience and outcomes. These metrics would enrich and strengthen the case for increased resources and support.

By expanding the scope of what we measure, we can refocus on the fundamentals of safe, patient-centered care. Hallway use metrics offer an opportunity to address the costs of crowding and advocate for solutions that improve the experience and outcomes for patients and providers alike.

References

- Wiler JL, Welch S, Pines J, Schuur J, Jouriles N, Stone-Griffith S. Emergency Department Performance Measures Updates: Proceedings of the 2014 Emergency Department Benchmarking Alliance Consensus Summit. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2015;22(5):542-553. doi:10.1111/acem.12654

- Hospitals – Timely & effective care | Provider Data Catalog. Accessed December 19, 2024. https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/topics/hospitals/timely-effective-care

- McClelland MS, Jones K, Siegel B, Pines JM. A Field Test of Time-Based Emergency Department Quality Measures. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2012;59(1):1-10.e2. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.06.013

- Derlet RW, Richards JR. Overcrowding in the nation’s emergency departments: Complex causes and disturbing effects. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2000;35(1):63-68. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(00)70105-3

- Richards JR, van der Linden MC, Derlet RW. Providing Care in Emergency Department Hallways: Demands, Dangers, and Deaths. Advances in Emergency Medicine. 2014;2014(1):495219. doi:10.1155/2014/495219

- Stiffler KA, Wilber ST. Hallway Patients Reduce Overall Emergency Department Satisfaction. The Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2015;49(2):211-216. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.05.002

- Richards JR, Derlet RW. Emergency Department Hallway Care From the Millennium to the Pandemic: A Clear and Present Danger. J Emerg Med. Published online September 11, 2022. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2022.07.011

- Kelen G, Peterson S, Pronovost P. In the Name of Patient Safety, Let’s Burden the Emergency Department More. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2016;67(6):737-740. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.11.031

- Berg E, Weightman AT, Druga DA. Emergency Department Operations II. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America. 2020;38(2):323-337. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2020.01.002

- Feizi A, Baker W. Limits of Capacity Flexibility: Impact of Hallway Placement on Patient Flow and Quality of Care in the Emergency Department. Published online September 23, 2021. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3929489

- Cairns C, Kang K. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2022 Emergency Department Summary Tables. Published online 2022.

- Cairns C, Kang K. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2019 Emergency Department Summary Tables. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.); 2019. doi:10.15620/cdc:115748

- Sartini M, Carbone A, Demartini A, et al. Overcrowding in Emergency Department: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions—A Narrative Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2022;10(9):1625. doi:10.3390/healthcare10091625

- Beniuk K, Boyle AA, Clarkson PJ. Emergency department crowding: prioritising quantified crowding measures using a Delphi study. Emerg Med J. 2012;29(11):868-871. doi:10.1136/emermed-2011-200646

- Solberg LI, Asplin BR, Weinick RM, Magid DJ. Emergency department crowding: Consensus development of potential measures. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2003;42(6):824-834. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(03)00816-3

Research

Laura Melville, MD MS

Associate Research Director

SAFE Medical Director

NewYork-Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital

Chair, New York Research Committee

Bernard P. Chang, MD PhD FACEP

Associate Dean of Faculty Health, Columbia University

Vice Chair of Research

Department of Emergency Medicine

Research Corner: Understanding Fentanyl Adulteration in Emergency Department Patients

Fentanyl has become a defining challenge in the world of substance use and emergency care. Originally a key player in opioid pain management, this synthetic opioid has infiltrated the illicit drug supply at an alarming rate. Its presence now extends beyond opioids like heroin into nonopioid substances, such as cocaine and methamphetamine, dramatically increasing the risk of overdose for unsuspecting users. For emergency departments (EDs), which often serve as the first point of contact for individuals experiencing drug-related crises, this development is reshaping the way we approach care.

A recently published study in Annals of Emergency Medicine, led by Dr. Dana Sacco, including those within New York ACEP’s research committee provides important insights into the scope of fentanyl adulteration, highlighting the deep connection between clinical work and academic inquiry. Their findings not only underscore the hidden dangers in the drug supply but also emphasize the critical role of emergency physicians in addressing this public health crisis.

A Hidden Epidemic

Between April 2022 and January 2024, researchers conducted a study at two New York City EDs: an academic medical center and a community hospital, both in northern Manhattan. Together, these sites see more than 145,000 patient visits annually, making them ideal locations to observe urban drug use trends.

The team enrolled 229 patients who arrived at the ED with symptoms linked to drug use, including overdose, intoxication or psychosis. Each participant provided a urine sample for fentanyl testing and self-reported the substances they believed they had used in the prior 24 hours. Many anticipated their results would align with their reports, but the testing revealed a far more complex reality.

Among those who knowingly used opioids, 89% tested positive for fentanyl. Of these, an astonishing 90% were unaware they had consumed fentanyl, highlighting the pervasive and hidden nature of its presence in the drug supply. But the surprises didn’t end there. Nearly a quarter of patients (24.5%) who believed they had used only nonopioid substances, such as cocaine or methamphetamine, also tested positive for fentanyl. For these individuals—who lack opioid tolerance—the risks are exponentially higher.

The findings reflect a grim reality: fentanyl has become a universal contaminant in the drug supply, creating dangers not only for those who intentionally use opioids but also for unsuspecting individuals using other substances.

Complex Challenges of Polysubstance Use

The study also revealed that many patients weren’t using fentanyl—or any other substance—in isolation. More than 80% of opioid users and nearly 60% of nonopioid users reported consuming multiple substances. Cocaine was the most common co-used drug in both groups, adding another layer of complexity to overdose management and treatment planning.

This trend toward polysubstance use complicates the already challenging task of providing care in the ED. When patients mix opioids with stimulants like cocaine, the risks of overdose and adverse interactions increase. Clinicians must consider the broader picture of substance use patterns when treating these patients, tailoring their interventions to address these overlapping risks.

The Role of the Emergency Department

For many individuals experiencing substance use crises, the ED is not just a place of treatment—it is their only contact with the healthcare system. This places emergency physicians in a unique position to intervene, educate, and support harm reduction.

One of the study’s key takeaways is the critical importance of patient education. Many of the patients who tested positive for fentanyl were unaware they had been exposed to it. This lack of awareness represents an opportunity for clinicians to provide information about the risks of fentanyl and tools that can help mitigate them. Fentanyl test strips, for instance, allow users to test their drugs for the presence of fentanyl before use, empowering them to make safer choices.

Beyond education, harm reduction strategies must be integrated into standard ED care. Providing naloxone kits, distributing fentanyl test strips, and discussing overdose prevention can save lives. These simple interventions, paired with clear and empathetic communication, have the potential to make a significant impact.

Building Beyond the ED

While emergency physicians can do much to address this crisis, broader systemic changes are essential. The ubiquity of fentanyl in the drug supply is a public health issue that requires coordinated efforts across healthcare, policy, and community organizations. Policymakers must invest in harm reduction initiatives, expand public education campaigns, and support research into effective interventions.

This study also highlights the need for further exploration of fentanyl-related challenges. For instance, how can harm reduction tools like test strips be most effectively distributed in EDs? What interventions are most likely to engage patients with polysubstance use? Answering these questions will require collaboration and innovation across multiple sectors.

Looking Ahead

Dr. Sacco emphasizes that addressing fentanyl adulteration requires a multifaceted approach. The ED plays a pivotal role, not just in responding to overdoses but in preventing them. Emergency physicians are uniquely positioned to lead the charge in harm reduction, advocacy and education. The fentanyl crisis is complex, but with research like this, we are gaining the knowledge needed to act. By integrating harm reduction strategies into clinical practice and engaging with patients about the risks they face, emergency physicians can make a meaningful impact. This study is not just a call to action—it’s a reminder of the vital role emergency medicine plays in addressing one of the most urgent public health challenges of our time.

New York EM Residency Spotlight

St. Joseph, Bethpage, NY

Demographics:

Program Director: Bob Gekle, MD FACEP

Program Coordinator: Maria Citera

Program Coordinator Email: Maria.citera@chsli.org

Hospital Capabilities: STEMI, Stroke

Total Number of EM Residents: 18

Inaugural Resident Class Year: 2024-2025

Benefits Offered: Rosh Review, Vision, Professional Liability Coverage, Membership Dues coverage, Life insurance, Dental Insurance, Lab Coats, Health Insurance, Disability insurance

Other Benefits Offered: Cell Phone Stipend, Educational Support stipend, Meal stipend, Rotational travel expense stipend, Uniform expense stipend, free parking, CME reimbursement

Instagram: @stjoseph_em

What is your programs most unique feature?: We view you as an “Emergency Physician in training” and from day 1, you get to provide what your patient needs while working one on one with an attending physician who is there to empower you to provide great emergency care. Residents, early on, get exposed to all pathology. For example in our inaugural class (2024-2025) our first year residents have already done many intubations, central lines, chest tubes, and transvenous pacemakers. The variety and severity of the pathology here would shock anyone who drove by our hospital and wondered what it’s like inside.

What Makes Your Program an Excellent Place to Complete a Residency?: Here, you get academic training at a community facility, where you have taken care of all patients yourself, rather than consulting the care and procedures to other medical specialties. You’ll be trained to work at any ED in the country without skipping a beat. You’ll get diverse/critical exposure as early as your first shift. Here you have ample opportunity to join committees and impact the direction of both the hospital and the residency. As a part of a smaller hospital, all of the people here are directly invested in your success.

Marc Kanter, MD FACEP

Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine

Program Director, Emergency Medicine Residency

Lincoln Medical & Mental Health Center

2020 and Beyond: What Is Your Capacity?

During a recent shift in the emergency department (ED), I was asked by a rotating student, “What was it like here during COVID”? Somewhat reluctantly, I started to think back to that time and truthfully, I am not sure how I answered him.

Almost exactly five years ago, I remember being on vacation reading articles about a concerning viral infection that was spreading through parts of Asia and Italy, as cases had just starting cropping up in California and Washington State. In only a few short weeks, on Sunday, March 1, 2020, we had the first confirmed case in New York State, in Westchester County. From that point on, the proverbial floodgates opened and the state was inundated with an exponential number of COVID cases for the foreseeable future. A State of Emergency was declared in New York State on March 7 and in the US on March 13. Bars, restaurants and schools closed a few days later and the New York State “Pause” began at 8pm on Sunday, March 22. We could all look back and remember so many different milestones from the early part of the pandemic. The deployment of military physicians to the state, the arrival of the US Naval Ship Comfort in New York Harbor, the creation of field hospitals in parks and arenas throughout the State, the need for refrigerated morgue trucks to accommodate the staggering number of deaths, pleas for personal protective equipment and of course the nightly celebration of healthcare heroes.

I don’t want to make this a full retrospective of the COVID-19 timeline in New York. Candidly, I still don’t know that I am ready to re-live those day-to-day happenings. Certainly, a lot has transpired in the world of healthcare since March 2020. We have seen shifts in staffing patterns, advances in technology, attrition in the workforce, major transformations to health systems, tighter operating margins for hospitals with increased financial complexities, changes in residency matching patterns, particularly in our specialty and so many more. To some, they may feel like not much has truly changed since pre-pandemic times, others may believe everything has changed.

One of the thoughts I keep coming back to when I look over the last five years, is the issue of capacity. Not the capacity of a patient, nor the capacity of the individual emergency medicine (EM) physician, but the capacity of our departments, hospitals and systems. Everyday healthcare business experts report on hospital and unit closures, mergers and reorganizations, not just throughout the country but regularly in our own State. As an EM physician, a parent or even a patient yourself, do you feel our healthcare system has more or less capacity to treat patients than five years ago? How about critically ill or injured patients? How about a massive number of critically ill patients for months at a time?

If you were to take an otherwise naive observer and explain that five years ago we had the deadliest pandemic in over a century, which stretched our healthcare system well beyond its limits, would they think we would take lessons learned and work to build something better, maybe more versatile? The obvious answer is yes, but the real question is, have we?

EDs across the state are challenged by high volume and acuity every day. This is only worsened by boarding due to lack of available inpatient beds or staffing on those units. In 2020, national ACEP sent a letter to the White House to sound the alarm about the national boarding crisis. In 2023, the New York State Public Health and Health Planning Council held a meeting to discuss issues around ED and Emergency Medical Services (EMS) wait times. There are regular reports across the State that outline significant increases in EMS offload times, in some taking hours for single patients. This is compounded by reports outlining an EMS workforce crisis in New York State over the last five years. What does this all mean? The standard for our healthcare system, without a global pandemic, is that patients wait longer to be brought to and evaluated in EDs, they wait longer to be moved upstairs and they may wait longer to be seen by specialists or be transferred to larger receiving centers.

Just in the last five years what kinds of added stressors have we seen that either did or could have had significant impacts to the care we provide? Of course, we still have COVID infections but as I write this, Influenza activity is widespread in New York State with over 50,000 positive cases. Just a couple of years ago we had a Tripledemic that caused significant surge particularly in the Pediatric Emergency Departments. We have seen several measles outbreaks, the emergence of Mpox, concern over the reappearance of Ebola, a Marburg virus outbreak, increases in Dengue infections and Avian Flu infections. We continue to struggle through the opioid epidemic with the additions of Fentanyl and Xylazine. There is the ubiquitous mental health crisis with a lack of available beds for patients needing inpatient care. Many of you had to manage horrific large-scale MCIs over the last few years. There have been ransomware attacks that have shut down IT systems for months across New York and most would argue that New York has an ever-prevalent threat of a terror attack.

I don’t mean to imply nothing has changed in the last five years. We have made some significant advances over that time. We have all seen the explosion of virtual care both for scheduled care but also for acute unscheduled care. We have colleagues around the State providing virtual care services to patients and physicians around the world. We have seen the expansion of all manners of tele-services in all of our systems. We have seen the maturation of many of the transfer centers across the State with some ability to level-load patients within the systems. There are certainly advances in technology with the use of AI, including early detection systems for potentially sick patients. Many agencies were involved in the ET3 program in New York State, piloting the transport of 911 patients to alternative destinations or providing treatment in-place with telemedicine physicians. Health systems in New York State have pioneered community paramedicine or mobile integrated health programs, nursing home telemedicine programs and hospital-at-home programs. New York City created the BHEARD program staffing mental health professionals on ambulances for behavioral health emergencies. Many of these initiatives attempt to keep and treat patients at home, avoid unnecessary ED visits and hospitalizations and hopefully expand access to patients. Again, the question is whether it is enough?

I would encourage all of you to continue to reflect on the events, not only of 2020, but also the intervening years. Don’t just think back to masks, vaccines, and ventilators, try to go beyond that. Continue to ask yourself, your colleagues and leaders the important questions; What has changed? Are we ready for the next big test? How adaptable is your Emergency Department? Hospital? System? What do you, your staff and the community have the capacity to manage? We should never forget those events, never stop asking the important questions and never forget just how important the voice of an Emergency Medicine Physician can be in shaping healthcare.

Emergency Medicine Resident Committee

Carlton C. Watson, MD MS

Chair, Emergency Medicine Resident Committee

PGY-3

Vassar Brothers Medical Center

Christopher J. Karnicki, MD MS

Emergency Medicine, PGY-2

SBH Health System – Bronx

Frontlines Under Fire: Defusing Workplace Violence in the Emergency Department

Workplace violence (WPV) refers to any act or threat of physical, verbal, non-verbal or written violence, harassment, intimidation or other disruptive behavior that occurs in a workplace setting.1 In the healthcare setting, specifically, the emergency department (ED), it encompasses acts of verbal abuse, physical assault or even severe incidents like use of weapons or firearms.6 Due to the unpredictable, high-stress, high acuity environment of the emergency department, this can often lead to, and/or exacerbate, acute agitation and aggressive behavior. The chaotic nature of emergency departments, coupled with overcrowding, treatment delays and boarding can contribute to the heightening of tension and emotional outbursts leading to violence towards staff.8

Emergency departments are susceptible to violence due to the nature of the services offered and the challenges that are inherent to daily practice.9 Providers frequently interact with individuals experiencing a range of issues including pain, mental health crisis, substance abuse or involvement in criminal activity. The primary focus always relies on patient care, despite personal risk, which often results in providers facing first-hand frustration from patients, visitors or other accompanying individuals. Many healthcare providers refrain from reporting incidents simply due to fear of retaliation or perception that the reports do not lead to meaningful action.10

For emergency department providers, workplace violence has had several serious repercussions which range from physical harm to psychological issues like anxiety, burnout and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).11 Recurrent exposure to acute agitation and violence can have a substantial negative influence on the mental health of providers, which can result in lower retention rates and staff shortages. In the end, these behaviors undermine the feeling of security in the job, causing providers to be always on guard. In addition to verbal abuse and threats, these problems frequently involve physical damage, which has a serious negative impact on the mental health and general wellbeing of the provider. According to the 2024 ACEP poll, more than nine in ten (91%) of emergency physicians reported being threatened or attacked in the past year which has eroded morale, causing them to reconsider their commitment to a field that is already fraught with numerous challenges.3

Workplace violence has had a negative impact on delivery of patient care, in addition to its direct effect on healthcare providers.12 When employees feel unsafe or work under duress, their ability to provide quality patient-centered care suffers. Violence in the emergency department frequently delays care for patients who require acute or critical care, as personnel focus their attention to attempting to handle acute agitation and aggression. In time-sensitive situations, disruptions in care can result in medical errors, poor patient outcomes and overall decreased efficiency.13 As an emergency medicine resident, working in an urban NYC safety net hospital, I have seen the impact of workplace violence on our specialty, our patient population and the broader medical community. A first-hand exposure with these difficulties highlights the importance of understanding that workplace violence is more than just “part of the job.”

Addressing workplace violence involves a complete approach and solution which involves drafting and implementing policies, offering education, improving security and addressing staff safety, communication and well-being.15 By training staff and providers in de-escalation techniques and situational awareness, centers will be better equipped to handle these situations more effectively. By employing on-site security personnel and adopting security protocols, this can help providers respond to acute agitation and/or violence while preventing potential outbreaks. In addition to preventative measures, employees who suffered the consequences of workplace violence should be provided with a support system which spans from counseling, peer support and policies that encourage the reporting of incidents without fear of retaliation.

Workplace violence in the emergency department not only endangers patients, but also jeopardizes the healthcare system’s ability to function successfully.16 The first step for institutions is to acknowledge the gravity of the situation and take action to protect their frontline workers. Reducing workplace violence is an important step in ensuring that providers in the ED can continue to provide high-quality lifesaving care that society relies on.17 By fostering this safety net action plan, this can allow ED providers to focus on what they do best: save lives.

References

- Stene J, Larson E, Levy M, Dohlman M. Workplace violence in the emergency department: giving staff the tools and support to report. Perm J. 2015 Spring;19(2):e113-7. doi: 10.7812/TPP/14-187. PMID: 25902352; PMCID: PMC4403590.

- Oztermeli AD, Oztermeli A, Şancı E, Halhallı HC. Violence in the Emergency Department: What Can We Do? Cureus. 2023 Jul 14;15(7):e41909. doi: 10.7759/cureus.41909. PMID: 37583738; PMCID: PMC10423942.

- When Emergency Physicians Regularly Fear Violence at Work, It’s Past Time for Change. American College of Emergency Physicians. April 16, 2024. Accessed January 7, 2025. https://www.acep.org/news/acep-newsroom-articles/when-emergency-physicians-regularly-fear-violence-at-work-its-past-time-for-change

- 18 Workplace Violence Reporting Behaviors in Emergency Departments across a Health System. McGuire, S. et al. Annals of Emergency Medicine, Volume 78, Issue 4, S8

- Alshahrani, M., Alfaisal, R., Alshahrani, K. et al. Incidence and prevalence of violence toward health care workers in emergency departments: a multicenter cross-sectional survey. Int J Emerg Med 14, 71 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-021-00394-1

- Phillips, J. P. (2016). Workplace Violence against Health Care Workers in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine, 375(7).

- Wong AH, Ray JM, Cramer LD, Brashear TK, Eixenberger C, McVaney C, Haggan J, Sevilla M, Costa DS, Parwani V, Ulrich A, Dziura JD, Bernstein SL, Venkatesh AK. Design and Implementation of an Agitation Code Response Team in the Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 2022 May;79(5):453-464. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2021.10.013. Epub 2021 Dec 1. PMID: 34863528; PMCID: PMC9038629.

- Locklear, M. Emergency department crowding hits crisis levels, risking patient safety. YaleNews. Sep 30, 2022. Accessed January 7, 2025. https://news.yale.edu/2022/09/30/emergency-department-crowding-hits-crisis-levels-risking-patient-safety

- D’Ettorre G, Pellicani V, Mazzotta M, Vullo A. Preventing and managing workplace violence against healthcare workers in Emergency Departments. Acta Biomed. 2018 Feb 21;89(4-S):28-36. doi: 10.23750/abm.v89i4-S.7113. PMID: 29644987; PMCID: PMC6357631.

- Spencer C, Sitarz J, Fouse J, DeSanto K. Nurses’ rationale for underreporting of patient and visitor perpetrated workplace violence: a systematic review. BMC Nurs. 2023 Apr 23;22(1):134. doi: 10.1186/s12912-023-01226-8. PMID: 37088834; PMCID: PMC10122798.

- Kafle S, Paudel S, Thapaliya A, Acharya R. Workplace violence against nurses: a narrative review. J Clin Transl Res. 2022 Sep 13;8(5):421-424. PMID: 36212701; PMCID: PMC9536186.

- Lim MC, Jeffree MS, Saupin SS, Giloi N, Lukman KA. Workplace violence in healthcare settings: The risk factors, implications and collaborative preventive measures. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2022 May 13;78:103727. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2022.103727. PMID: 35734684; PMCID: PMC9206999.

- Monteiro C, Avelar AF, Pedreira Mda L. Interruptions of nurses’ activities and patient safety: an integrative literature review. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2015 Jan-Feb;23(1):169-79. doi: 10.1590/0104-1169.0251.2539. PMID: 25806646; PMCID: PMC4376046.

- Blando J, Ridenour M, Hartley D, Casteel C. Barriers to Effective Implementation of Programs for the Prevention of Workplace Violence in Hospitals. Online J Issues Nurs. 2015 Jan;20(1):5. Epub 2014 Dec 4. PMID: 26807016; PMCID: PMC4719768.

- Jones CB, Sousane Z, Mossburg S. Addressing Workplace Violence and Creating a Safer Workplace. PSNet. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, US Department of Health and Human Services. 2023.

- Al Khatib O, Taha H, Al Omari L, Al-Sabbagh MQ, Al-Ani A, Massad F, Berggren V. Workplace Violence against Health Care Providers in Emergency Departments of Public Hospitals in Jordan: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023 Feb 19;20(4):3675. doi: 10.3390/ijerph20043675. PMID: 36834370; PMCID: PMC9964576.

- Wirth T, Peters C, Nienhaus A, Schablon A. Interventions for Workplace Violence Prevention in Emergency Departments: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Aug 10;18(16):8459. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18168459. PMID: 34444208; PMCID: PMC8392011.

Education

Sophia Lin, MD FPD-AEMUS

Assistant Professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine and Clinical Pediatrics

Director of Emergency Ultrasound

Department of Emergency Medicine

Weill Cornell Medicine

Sarah Smetana, MD

Medical Education Fellow

University of Rochester Medical Center

Lindsey Picard, MD

Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine and Pediatrics

Assistant Program Director of Emergency Medicine Residency

Director of Medical Student Electives

Co-Director of Medical Education Fellowship

University of Rochester Medical Center

“Trust the Process”: Faculty and Former Resident Perspectives on Remediation

Remediation, a word that some residents may equate to failure, stigma or anxiety, has developed into a process that emergency medicine residents at the University of Rochester Medical Center (URMC) can speak openly about and feel supported by faculty invested in their professional growth and success. This discussion will present a former resident’s perspective on our remediation process, followed by a faculty member’s perspective on building this process over the last three years.

Resident Experience

As a first-year resident, it was not uncommon to hear multiple senior residents openly talk about being on remediation. The culture surrounding remediation seemed open, casual and low-pressure. Many residents would be on it temporarily and then get off the following year with no issues or impact on their permanent record. Residents entered the program knowing that falling below a predetermined threshold on the yearly in-service training exam (ITE) would automatically result in being placed on ITE remediation. Since the program published this policy in advance, residents had clarity about their expectations. They would not be left wondering why they later got an email stating they were on remediation. If placed on remediation, residents had a clear and defined goal to work towards in terms of demonstrating knowledge competency on the ITE the following year. Removing the uncertainty about why a resident was placed on remediation emphasized that a standard was unmet. Falling short of this standard was not a personal flaw or a failure to be ashamed of but simply an acknowledgment that a resident needs more support and dedicated time to improve that competency area.

While many residents on remediation come from failing to meet this objective standard, some are placed on remediation due to clinical or professional competency deficiencies as determined by faculty and staff feedback. The reasons for placement on clinical or professional remediation may be more nuanced, but regardless of the remediation type, this creates a cohort of residents who share the remediation experience. This shared experience decreases feelings of isolation and encourages residents to overcome competency roadblocks, like their peers before them, if placed on remediation. Encouragement comes from this group of peers but also through multiple faculty members who are involved with this process. All residents on remediation are assigned to a faculty advisor to help set learning goals, strategize study plans and schedule regular check-ins to ensure objectives are met. The assigned faculty members are readily available and are integral to supporting students toward success.

After graduating from this program this past summer, my perspective on remediation has shifted and I am confident speaking openly about my own remediation experience. Along with many of my peers, I found myself placed in ITE remediation my first year; however, instead of feeling any negative emotion, I saw remediation for what it was – a knowledge deficiency. I was not caught off guard, I was not alone and I knew I could improve my performance the next time. I knew I had not performed well due to a lack of dedication towards preparing as external factors were competing for my attention. Entering this low-pressure remediation process helped highlight a deficiency in my knowledge and forced me to set a specific goal to achieve. Despite no longer being on remediation the following year, I stayed dedicated to proving I knew my material. The framework I developed for balancing work and studying stayed with me throughout my years of training, leading me to this past fall, where I felt confident taking the boards and passing on my first attempt. Remediation provided a safety net of accountability and attention that sparked my intrinsic motivation for success. My faculty mentor and peers added security and support and promoted a safe place for learning and developing as a physician. While in the past I may have considered remediation to be intimidating or to provoke negative thoughts, I found that it provided a positive impact on my resident experience and career.

Remediation Director

Agreed, remediation is such a simple word that it can have an intimidating connotation. As the faculty director of remediation for the emergency medicine residency program at URMC, one of my main goals is to dispel this negative implication of the idea of remediation. Residents can be a part of two main types of remediation during their training: in-service training exam (ITE) remediation and clinical and/or professional remediation (i.e., academic warning). I am heavily involved in my role as faculty director of remediation and as one of the assistant program directors for the residency. At URMC, we value our residents, their education and their remediation journey, so much so that a core faculty member is assigned as the faculty director of remediation. This ensures a dedicated point person for the residents to reach out to and use as a resource, as the core faculty member’s academic responsibilities are focused on the residents’ overall educational success.

After taking over the faculty director of remediation position three years ago, I have adapted and redesigned the remediation process here at URMC. Initially, the outgoing remediation director told me that there were typically 5-6 residents per year on ITE remediation. She passed along her approach and resources that have been useful. Remediating 5-6 residents a year felt very doable and I was eager to start, but after the first ITE exam since taking over, to my surprise, the number of residents per year doubled (11). With this drastic increase in residents needing remediation, the time commitment I had foreseen for myself in this new role had significantly changed. Using the former director’s guidance, my initial approach to remediation was to meet with each resident and follow up periodically throughout the year to ensure their compliance with the study plan we had created and as a resource for their questions. I soon realized that this approach would not be sustainable year to year with higher resident numbers requiring remediation and that one person overseeing 11 residents’ academic performance alone was not feasible without help. This motivated me to change our residency’s approach to ITE remediation.

Several different aspects of residency remediation could benefit from revamping our former approach. Meeting with residents once shortly after they “failed” the ITE and following up periodically throughout the year was a cookie-cutter approach to remediation as a whole. Yes, in my experience, many residents placed on remediation simply did not study or take the exam seriously enough to pass the ITE. These individuals likely benefit from the cookie-cutter approach to remediation as they just need to be held accountable for their time and studying. Yet, another subset of residents on remediation will need more than just an accountability partner. Initial meetings with each resident placed on remediation are crucial; this allows one-on-one time with me to address the issue or issues that impacted their ITE score. Additionally, each resident is sent a list of questions before this initial meeting about their current study approach, past testing experiences, learning style, etc., to facilitate a constructive discussion during this initial meeting. Taking the rest of the remediation process steps further and making the remediation approach personalized to each resident is a key component to redesigning ITE remediation.

In brainstorming how to approach remediation best going forward, there were new goals to focus on: managing more residents than previously anticipated for their ITE remediation, developing numerous individualized study plans for residents on remediation and intervening early in residency. Staying current on the resources residents use and what is out there is key to providing our residents with the best to succeed in residency and beyond. Textbooks are still helpful in understanding foundational knowledge for emergency medicine. Yet, podcasts, lecture videos and online resources are becoming more readily available and comprehensive in their emergency medicine information. Our residency provides each resident with an annual question bank subscription that ensures access to practice board/ITE questions to facilitate active studying and learning. Rising PGY3 residents placed on remediation receive a national board review course completed during an elective week of their third year. Given the growing number of resources out there due to technology and the internet, it is stressed to residents that using too many resources can be just as detrimental as not using any at all, causing what I like to call “resource fatigue.”

During my second year as remediation director, I implemented the team approach to remediation by creating a small team involving junior and senior faculty members. This team meets in the spring each year to discuss each resident, identify their current struggles with ITE studying and then generate individualized study plans for each resident. Everyday struggles identified include one or a combination of the following: medical knowledge, executive functioning skills, time management, test-taking skills and life outside of residency (health issues, family needs, etc.). After this spring meeting, each team member would be assigned 1-2 residents on remediation and act as their point person for the upcoming academic year regarding their remediation process. Working closely with the residents as APD and clinically, I was able to place residents with specific faculty members from the remediation team that would best serve them, whether it be personality compatibility, faculty with similar struggles in the past and their ability to relate, additional educational training by certain faculty members, etc.

As for intervening earlier in residency, interns were the main focus of these interventions. Our interns have 5 weeks of orientation, including lectures, skill labs and clinical shifts. I added a lecture to this orientation time that addresses how to study as a resident, stressing that residency is a whole new ballgame compared to their time as a medical student and also focusing on all the resources we offer here at URMC. Additionally, a mock ITE exam has been added to the orientation time to help residency leadership and the interns identify who may benefit from early intervention from the remediation team. This lecture and mock ITE in orientation have prompted interns to schedule meetings with me to develop a study approach early in their intern year rather than waiting to “fail” the ITE in February. Additionally, in December each year, starting in 2022, residency leadership, including myself, implemented a mandatory mock ITE for all residency years, after which, pending the results, I would reach out and offer my assistance to residents with their current study approach and how to modify it for the upcoming months best leading up to the actual ITE.

Interestingly, the number of residents requiring ITE remediation has remained high. As previously mentioned, my first year was 11; my second and third years were 12 and 11, respectively. Most residents come off remediation the following year and the success rate has varied between roughly 60-72% since starting as remediation director. Since implementing this process, a total of 16 PGY1 residents did not meet the expected ITE score and were placed on ITE remediation. Of these, 10 residents met the standard set for the PGY2 year ITE and were removed from remediation. Seven PGY2 residents were placed on ITE remediation with 5 residents meeting expectations. The two PGY2 residents who did not meet the expected ITE score were on remediation during their entire time as residents and required much more assistance and resources compared to the other residents on remediation, i.e. extra meetings with faculty and follow up and an additional meeting with our university undergrad campus’ Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning that specializes in test-taking skills. Although “passing” ITE scores are not required for graduation, this process may be informative to individual residents as they prepare to take their EM boards. It is unclear why the resident numbers on remediation remain high, yet after seeing the ABEM board pass rate this year for 2024 graduates, there seems to be a national trend. So why are more residents on remediation now compared to the board pass rate drop this year? This is a question many PDs and APDs are struggling with right now. Our residency leadership team and I have tried to brainstorm different possibilities; for example, these residents were heavily affected by the COVID pandemic, more medical schools are passing/failing now rather than a graded curriculum, step examinations are now pass/fail, residents may be struggling with the transition to residency, study resources and techniques used in medical school are not translating into residency/boards studying, etc. The list can continue as this is a multifactorial problem. By considering these factors and knowing that the educational landscape is ever-changing these days, residency leadership and I have been flexible and adaptable in our approach to ITE remediation. We are always discussing new ways to serve our residents and their academic success best.

In conclusion, how do I approach making remediation less intimidating and a more positive experience? My three main approaches include normalizing remediation, openness among residents and the team approach. Starting in my first meeting with residents, I always stress that remediation is not a punishment and that I am here mainly as a resource to help them succeed academically as a resident. Normalizing that many residents have been placed on remediation over the years and perform well on their boards after residency is a comfort to most residents. Knowing that others before them went through this also helps them feel comfortable talking with other current residents as a support throughout the process. Remediation is confidential for the residents, yet here at URMC, the residents are very open and confide in each other with this information. Generally, it is known by the residency as a whole, by the residents’ choice, who is on remediation and who is not. This openness creates a supportive learning environment that is conducive to collaboration. I have had the privilege of setting up group study sessions for residents with faculty members to meet and discuss the faculty member’s approach to board-style questions and give advice on their study habits and resources. Lastly, the team approach to remediation; by creating a faculty remediation team, the residents get a more well-rounded approach to their study plans and coaching throughout the year on their ITE remediation. Remediation is a team sport that takes buy-in from all parties, residents and faculty alike; here at URMC, we take this very seriously to ensure the best outcome for our residents’ academic success year in and year out.

Resources

Murano T, Smith JL, Weizberg M. Remediation Strategies for Emergency Medicine Patient Care Milestones. Cureus. 2018 Nov 7;10(11):e3557. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3557. PMID: 30648089; PMCID: PMC6324861.

Council of Residency Directors in Emergency Medicine Remediation Resources https://www.cordem.org/resources/residency-management/remediation-resources

Membership Engagement and Development

Moshe Weizberg, MD FACEP

Medical Director, Emergency Department

Maimonides Midwood Community Hospital

Chair, New York ACEP Professional Development Committee

Interviewer

William Caputo, MD MS FACEP

Residency Director, Associate Chair of Training and Education

Department of Emergency Medicine

Northwell Health at Staten Island University Hospital

Interviewee

Elias Youssef, MD MBA FACEP

Chair, Department of Emergency Medicine

New York City Health + Hospitals / Kings County

Interviewee

Brittany Choe, MD MBA

Medical Director, Department of Emergency Medicine

New York City Health + Hospitals / Kings County

Interviewee

Daniel Skvirsky

Assistant Director, Department of Risk Management

New York City Health + Hospitals / Kings County

Artificial Intelligence (AI) in Healthcare: Friend or Foe?

Introduction

It was my privilege to speak with Dr. Elias Youssef, Dr. Brittany Choe, and Mr. Daniel Skvirsky, who are well known for keeping New York City Health + Hospitals / Kings County ahead of the curve as one of the elite hospitals in New York City.

This topic is extremely important because of the increasing impact of AI in medicine. As the current president of the American Medical Association Jesse Ehrenfeld stated, “It is clear to me that AI will never replace physicians — but physicians who use AI will replace those who don’t.”

Thank you all for taking the time to participate in this interview.

What is Artificial Intelligence?

DS: Broadly speaking, Artificial Intelligence (AI) refers to the capability of machines or computer systems to carry out tasks that typically require human intelligence. Examples include learning from data, interpretation of language, pattern recognition and complex problem solving. AI systems are trained on large amounts of data to identify patterns and utilize those patterns to make predictions or decisions about new information. Over time, these systems are fine-tuned for specific use cases.

How does your department use AI on a daily basis?

EY: We utilize AI to help expedite the care of patients with stroke and large vessel occlusion (LVO). We currently employ software that aids in the early identification of patients who may be candidates for thrombectomy and advanced intervention. This early notification process enhances our ability to mobilize resources and improve our door to intervention intervals. An added benefit of this AI tool is the resilience it has demonstrated in the setting of other system information technology (IT) failures and downtime. As long as we have the ability to perform a study, the tool will communicate with our Stroke Teams to help identify high risk patients.

What are some other applications of AI in healthcare?

EY: A new tool was just approved by the FDA to flag potential Pulmonary Embolism (PE) cases in real-time to assist Radiologists in prioritization and review of critical findings.1 AI systems are also being developed to highlight suspicious areas on malignancy pre-screening scans, which may help reduce time-to-diagnosis and enable faster decision-making.2 However, as with any tool that aids in disease screening, we must be mindful of the screening parameters that are set and the downstream effects of over testing and unnecessary procedures.

BC: AI models can analyze patient data to identify early signs of sepsis, which allows for more expedient intervention. One study demonstrated how a machine learning system used in five hospitals over a two-year period was able to identify patients with early signs of sepsis.3 Additionally, AI may allow clinicians to extract greater data from non-contrast CT scans as there is available literature highlighting the ability to detect malignancy for specific cohorts.4 The ability to obtain non-contrast studies may be in alignment with other patient-centered initiatives aimed to reduce repeat IV access attempts and unnecessary contrast loads. Such technology may also aid our outpatient colleagues performing malignancy evaluation as the lack of required contrast obviates the need for routine labs prior to image completion.

Can AI be used to improve hospital operations and patient flow?

EY: Researchers have demonstrated the utility of AI systems in predicting anticipated patient length of stay (LoS) and risk factors for 30-day readmission, providing data-backed insights that complement clinical expertise.5,6 This results in improved resource optimization, including bed allocation and strategic staffing plans. AI is also being studied as a way to assist in patient triage and reduce treatment intervals. Large hospitals are studying the implementation of a model which generates risk-driven triage acuity recommendations.7

DS: Machine-learning algorithms also have the potential to facilitate disease outbreak prevention efforts through early detection of high-risk areas. AI models have been studied using data from historical disease outbreaks to identify patterns in prohibitively large sets of environmental, demographic and epidemiological data.8,9 Additionally, AI lends itself to accelerating the development of new vaccines. During the COVID-19 pandemic, AI played a role in the rapid development of mRNA vaccines.10

How can AI contribute to the financial health of an organization?

EY: AI has shown great potential to improve the financial health of healthcare institutions, through optimization of revenue cycle management, improvement of billing and coding processes and by reducing administrative costs. AI programs can automate claims submission and facilitate timely and accurate reimbursement.11

BC: AI can reduce administrative costs by significantly reducing or even eliminating repetitive tasks, which can free up staff to focus on higher-value activities. Additionally, by analyzing current and historical data, AI models can assist in more accurately forecasting patient admissions, which can lead to more optimal staffing and resource allocation.

What are your top pearls for getting started and using AI in Medicine?

1) Identify specific problems and use cases in your department. Start with issues AI can address.

2) Choose the right tools and partners. Evaluate AI solutions carefully and comprehensively, focusing on reliability, ease of integration and alignment with regulatory compliance. Find reputable vendors which offer data-driven solutions to your specific use-cases.

3) Make sure you have quality data to train the model.

4) The key is to scale gradually; start small and ease into model expansion. Make sure the AI fits well into your existing workflows and ensure your staff is provided sufficient training for adoption.

5) Monitor and evaluate the performance of your system. Vendors can provide simulation or historical data, but real-world results are key. Continuously assess your system’s performance for accuracy, efficiency, and patient outcomes.

What are the pitfalls of AI?

DS: AI Model Collapse, though mostly theoretical, is a phenomenon characterized by model performance degradation over time, predominantly due to the reliance on repetitive or flawed training data. Current research and implementation data indicate that continuous human oversight, integration of diverse, high-quality data, ongoing generations of human-derived data and effective data management practices mitigate the likelihood of such a scenario.